[Broadway Ad Network]

[Broadway Ad Network]

TICKET / INFO

- StudentRush

- New York Show Tickets

- Givenik.com

- Telecharge.com

- Ticketmaster.com

- Group Sales Box Office

- Frugal TheaterGoer

- Broadway for Broke People

- Playbill's Rush/Lottery/SR

- Seating Charts

COMMUNITY

NEWS

- Back Stage

- Bloomberg

- Broadway.com

- BroadwayWorld

- Entertainment Weekly

- NYTheatre.com

- New York Magazine

- The New York Daily News

- The New York Post

- The New York Times

- The New Yorker

- Newsday

- NiteLife Exchange

- Playbill

- Show Business Weekly

- The Star-Ledger

- Talkin'Broadway

- TheaterMania.com

- Time Out New York

- American Theatre Magazine

- Theatre Development Fund (TDF)

- Best of Off-Broadway

- The Village Voice

- Variety

- The Wall Street Journal

- Journal News

REVIEWS

- The New York Times

- Variety

- New York Post

- NY1

- Aisle Say

- CurtainUp

- DC Theatre Scene

- Show Showdown

- Stage and Cinema

- StageGrade

- Talk Entertainment

- TotalTheater.com

- Off-Off Broadway Review

- TheaterOnline.com

- TheaterScene.net

- TheaterNewsOnline.com

WEST END

- The Stage

- 1st 4 London Theatre Tickets

- Book Your Theatre Tickets

- Compare Theatre Tickets.co.uk

- Theatre.com

- Whatsonstage.com [UK]

- ATW - London

- Musical Stages [UK]

- Albemarle of London

- Londontheatre.co.uk

- Google News

- Show Pairs

- ILoveTheatre.com

- The Official London Theatre Guide

- UK Tickets

BOSTON

CHICAGO

LA/SF

COLUMNS

- Peter Bart

- Andrew Cohen

- Ken Davenport

- Tim Dunleavy

- Peter Filichia

- Andrew Gans

- Ernio Hernandez

- Harry Haun

- Chad Jones

- Chris Jones

- James Marino

- Joel Markowitz

- Matthew Murray

- Michael Musto

- Ellis Nassour

- Tom Nondorf

- Richard Ouzounian

- Michael Portantiere

- Rex Reed

- Michael Riedel

- Frank Rizzo

- Richard Seff

- Frank Scheck

- Mark Shenton

- John Simon

- Robert Simonson

- Steve on Broadway (SOB)

- Steven Suskin

- Terry Teachout

- Theater Corps

- Elisabeth Vincentelli

- Hedy Weiss

- Matt Windman

- Linda Winer

- Matt Wolf

PODCAST

RADIO

TV

- Theater Talk

- BlueGobo.com

- Classic Arts Showcase

- American Theatre Wing Seminars

- Women in Theatre

- NY1

- WCBS [2]

- WNBC [4]

- FOX [5]

- WABC [7]

- WWOR [9]

- WPIX [11]

- Channel 13

- Hulu

- YouTube

AWARDS

- Tony Central

- Oscar Central

- Tony Awards

- Drama Desk Awards

- The Drama League Awards

- Lortel Awards

- Academy Awards

- Emmy Awards

- Grammy Awards

- GoldDerby

DATABASE

- Internet Broadway Database

- Internet Off-Broadway Database

- Internet Movie Database

- Internet Theatre Database

- Musical Cast Album Database

- [CastAlbums.org]

- Show Music on Record Database (LOC)

- CurtainUp Master Index of Reviews

- Musical Heaven

- StageSpecs.org

ROAD HOUSES

- Gammage [AZ]

- Golden Gate [CA]

- Curran [CA]

- Orpheum [CA]

- Community Center [CA]

- Civic [CA]

- Ahmanson [CA]

- Pantages [CA]

- Temple Hoyne Buell [CO]

- Palace [CT]

- Rich Forum [CT]

- Shubert [CT]

- Bushnell [CT]

- Chevrolet [CT]

- Broward Center [FL]

- Jackie Gleason [FL]

- Fox [GA]

- Civic Center [IA]

- Cadillac Palace [IL]

- Ford Center/Oriental [IL]

- The Bank of America Theatre [IL]

- Auditorium Theatre of Roosevelt University [IL]

- Kentucky Center [KY]

- France-Merrick [MD]

- Colonial [MA]

- Wilbur [MA]

- Charles [MA]

- Wang [MA]

- Wharton Center [MI]

- Whiting [MI]

- Fisher [MI]

- Masonic Temple [MI]

- Orpheum, State, and Pantages [MN]

- Fabulous Fox [MO]

- New Jersey PAC [NJ]

- Auditorium Center [NY]

- Proctors [NY]

- Shea's PAC [NY]

- BTI Center [NC]

- Blumenthal PAC [NC]

- Schuster PAC [OH]

- Playhouse Square [OH]

- Aronoff Center [OH]

- Ohio [OH]

- Victoria Theatre [OH]

- Birmingham Jefferson [OH]

- Merriam Theater [PA]

- Academy of Music [PA]

- Benedum Center [PA]

- Providence PAC [RI]

- Orpheum [TN]

- Hobby Center [TX]

- Music Hall [TX]

- Bass Hall [TX]

- Paramount [WA]

- Fox Cities PAC [WI]

- Marcus Center [WI]

- Weidner Center [WI]

FESTIVALS

- The New York International Fringe Festival

- The American Living Room Festival

- Summer Play Festival

- The New York Musical Theatre Festival

- Adirondack Theatre Festival

- NAMT: Festival of New Musicals

SPECIAL

- BC/EFA: Broadway Cares / Equity Fights AIDS

- The Actors' Fund

- Stage Directors and Choreographers Foundation

EDUCATION

- Google Shakespeare

- Actor Tips

- AACT

- ArtSearch

- Broadway Classroom

- Broadway Educational Alliance

- Camp Broadway

- Great Groups - New York Actors

- Theatre Communications Group (TCG)

- Theatre Development Fund (TDF)

- Off-Broadway Theater Information Center

UNIONS/TRADE

- AEA

- SAG

- AFTRA

- AGMA

- The League

- APAP

- Local 1

- ATPAM

- IATSE

- AFM

- AFM - Local 802

- Treasurers & Ticket Sellers Union

- DGA

- Dramatists Guild

- USA 829

- WGA, East

- WGA, West

- SSD&C

- AFL-CIO

- League of Professional Theatre Women

NYC NON-PROFITS

- Cherry Lane Theatre

- City Center

- Drama Dept.

- Ensemble Studio Theater

- Jean Cocteau Rep.

- Lark

- Lincoln Center Theater

- Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts

- Lucille Lortel Foundation

- Manhattan Theatre Club

- MCC

- Mint

- Pearl Theatre Company

- Public Theater

- Roundabout

- Second Stage

- Signature

- The Vineyard Theatre

- The York Theatre Company

REGIONAL

- Actors Theatre

- Alabama Shakespeare Festival

- Alley Theatre

- ACT

- American Musical Theatre in San Jose

- American Repertory

- Arena Stage

- Barrington Stage Company

- Bay Street Theatre

- Berkeley Rep

- Casa Manana

- Chicago Shakespeare Theater

- Cincinnati Playhouse

- CTC

- Dallas Summer Musicals

- Dallas Theater Center

- Denver Center

- George Street

- Goodman

- Guthrie

- Goodspeed

- Hartford Stage

- Hudson Stage Company

- Theatre de la Jeune Lune

- Kennedy Center

- La Jolla

- Long Wharf

- Lyric Stage

- Mark Taper Forum

- McCarter

- New Jersey Rep

- North Shore

- Old Globe

- Ordway

- Oregon Shakespeare

- Paper Mill

- Prince Music Theater

- The Rep (St. Louis)

- Sacramento Music Circus

- San Francisco Mime Troupe

- Seattle Rep

- Shakespeare Theatre Co. (DC)

- The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey

- South Coast Rep

- Steppenwolf

- Theater of the Stars (GA)

- Theater J (DC)

- Theater Under the Stars (TX)

- Trinity Rep

- Two River Theater Company

- Utah

- Victory Gardens

- Westport

- Williamstown

- Yale Rep

KEWL

An Uncomfortable Visit to the Boundaries of Show Business by Matthew Murray

-

Late in the first act of The Visit, the long-aborning musical that completed its run last week at the Signature Theatre in Arlington, Virginia, there is one moment that promises musical-comedy satisfaction.

Late in the first act of The Visit, the long-aborning musical that completed its run last week at the Signature Theatre in Arlington, Virginia, there is one moment that promises musical-comedy satisfaction.The mayor of the despondent town of Brachen leads his citizens in "a little spectacle, a tableau vivant with music," to compel Claire Zachanassian, Brachen's most famous former resident and the richest woman in the world, to bestow her financial blessings on the anemic community of her youth. The music for their entertainment is thigh-slapping in a tradition warmly befitting the Switzerland setting, the melody one that might pervade a Biergarten in the early hours of the evening before its patronage is thoroughly soused.

"Many years ago in Brachen / Joy would overflow in Brachen / Everything was bright here / Absolutely right here / Goethe spent the night here," the mayor sings. "We all got rich during World War II / And we couldn't sell our cuckoo clocks faster," he intones as, behind him, a dozen or so Brachenites recreate one such clock, complete with ardent vocalizing the avian sound that greets every hour.

Suddenly, the accompaniment grows broadly tragic: "Then all of a sudden / From out of the blue / We were faced with a terrible disaster / Our factory closed / Our economy died / And we found ourselves deeply in hock / Everything went wrong / Something silenced the song / Of our dear little cuckoo clock." The clock's music may have been stilled, but the Brachenites' hope has not been: Even as they swing back to exultation, it's clear that no hardship has tainted their inborn love of—and need for—performing. It's all very charming.

But what's it doing in The Visit?

In the canon of composing team John Kander and Fred Ebb (who died in 2004), this is nothing new. Many of their shows have turned on the idea that the world—for better or worse—revolves around show business. So it's not entirely unsurprising that this notion would appear in their score for this adaptation of Friedrich Dürrenmatt's 1956 play of the same title. (Terrence McNally wrote the book for the show, which was first produced at Chicago's Goodman Theatre in 2001.) What's more shocking is that it has achieved pride of place in a show in which it manifestly does not belong.

This philosophy of life in the spotlight is most readily apparent in Kander and Ebb's two most significant hits. In Cabaret (1966), the first mainstream concept musical hit, brassy and bawdy songs rife with ironic commentary irrupted into a tense story of love, decadence, and social blindness in Weimar Germany in the years before World War II. Chicago (1975) saw as crucial (and dangerous) the incestuous relationship between crime, news, and entertainment, as two women ascend to vaudeville superstardom after murdering their husbands and being exonerated by the court of public opinion. (This message has proven so trenchant today, it's propelled the show's 1996 Broadway revival to far greater success than the original production enjoyed.)

But even more minor titles found crucial connections. Zorba (1968) examined the necessity of storytelling and folklore in maintaining the necessary bonds in a small and tightly knit community. Molina, a gay prisoner in Kiss of the Spider Woman (1992), finds solace and salvation in his memories of the flickering images of a screen song-and-dance siren named Aurora. Steel Pier (1997) used the 1930s dance marathon as a metaphor for Depression-era romance and redemption. The Kander & Ebb musicalization of Thornton Wilder's The Skin of Our Teeth, titled All About Us, hews closely to the original play's vision of American progress as a play forever in rehearsal. And in Curtains, which completes its 15-month Broadway run this weekend, the lines between theatre and law blur when a Boston cop becomes embroiled in a murder plot—and a show that's dead in the water.

None of these works, however, struggles with a provenance as dark as that of The Visit. Dürrenmatt's play, most famous for the Maurice Valency adaptation that served as Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne's Broadway swan song in 1958 (and was the basis for McNally's book here), is a stinging indictment of greed and appeasement in a world that was preparing to enter the chilliest part of the Cold War. In Dürrenmatt's version, which was set not in neutral Switzerland but "somewhere in Central Europe" (in a town named Güllen, which in German means "liquid manure"—a far cry from Brachen, which in the same language merely means "broke"), Claire was willing to bestow her gift of one billion marks on her childhood home, with but one string attached: The residents must in turn take the life of Anton Schill, the man who wronged her some four decades earlier, and present her with the body.

"But justice cannot be bought," the mayor tells her.

Her response is as straightforward as it is tumultuous: "Everything can be bought."

The play then proceeds to prove her right. Schill is thrust into an atmosphere of fear and suspicion, while the townspeople begin purchasing luxury items on credit, thus changing their want into a need so virulent that Schill's fate is assured long before the curtain rings down on the second of the non-musical Visit's three acts. You can all but see the corruption, as increasing numbers of townsfolk are clad in yellow shoes and even the town's most upright citizens begin to understand how sacrificing Schill is the only answer for their crippling question.

Show business is not a part of these characters' lives. There are a couple of songs, but they serve only as weak tributes to Claire, the faint (and fallow) whisperings of a people who have nothing left. The harsh spotlight of the media frenzy that erupts late in Act III forces the inhabitants to couch their evil in easily digestible words for their own sakes, but that too is strictly borne of necessity. Their souls are as bleak as their town, and not being aided down the path to light or enlightenment.

Is this musical territory at all? The grim nature of every word, every symbolic speech, and tortuously planned gesture, suggests an opera, in which the vast expanse of lifelessness and the depths of despair in which everyone is floundering can be most readily explored. What it never suggests is a musical with more than trace amounts of lightness, in which all the characters are so focused on the past that they're unable to fix their gazes on the future.

Yet this is precisely what Kander, Ebb, and McNally deliver with their tonally confused treatment. The spirits of the younger Claire and Anton (here renamed Schell) haunt the older versions with visions of bodies and beauty faded. The older duo sings openly of their love for each other, and hint openly at the (however slim) possibility of reconciliation before the prescribed end. Claire's retinue, including two bodyguards, two blind men who factor in Anton's history, and her personal butler, are deeply enough devoted to her that they sing passionately of their ties in "I Would Never Leave You" before leading her in a rapturous, if necessarily tentative, tango. (Anton's rejection of Claire literally cost her an arm and a leg.)

But for The Visit, with songs or without, to devastate, we must believe that Claire, her entourage, and Anton are already as dead inside as the town is outside. The affirmation of life, or even the recognition of it, must be so foreign that the exercises everyone undertakes reek as much of futility as they do of expediency. Granting the town energy enough to conceive and execute their mini musicale, Claire the emotional fortitude to recount in song her litany of marriages or sing of her enduring torch in the late-show "Love and Love Alone," Anton sufficient presence of mind to recall Claire fondly before she reveals her disruptive hand, or either Claire or Anton a nature introspective enough to summon the ghosts of their vanished youth is to humanize that which long ago ceased being human.

Without the additional unforgiving weight, the musical Visit can't support Dürrenmatt's contention about humanity's malleable morality (which, otherwise, remains more or less intact). What's left is an uneasy melange of styles and feelings that range from Big Broadway to Weill Germany (it's easy to imagine the vodka-drenched "Love and Love Alone" being crooned by Lotte Lenya once upon a time). In the Signature production, which was intelligently directed by Frank Galati, somewhat less astutely choreographed by Ann Reinking (with far too much flash), and compellingly acted by a cast led by Chita Rivera (Claire), George Hearn (Anton), and Mark Jacoby (the mayor), all this was given mordant life. But even in these unusually capable hands, only once did all the elements ever coalesce into electrifying theatre.

That would be the first-act finale, "Yellow Shoes." This cunning compression of the play's entire second act tracks Anton's descent into a personal hell of Claire's indirect creation, as he finds his friends and family turning against him in a hurricane of passive-aggressive desperation. The loneliness thrust upon Anton during this majestic 10-minute musical scene drips with the terror of a life crumbling and a world disintegrating into capitalistic lawlessness.

It's an acutely effective expression of the core theme as rendered in song. Unfortunately, the horrific heights reached in "Yellow Shoes" are not sustained through the rest of The Visit. Kander, Ebb, and McNally too often allow themselves to sink into the easier answers of theatrical artifice as the antidote to life's ills, rather than just accepting—as Dürrenmatt did, and as we all eventually must—the sad truth that for some diseases there is simply no cure.

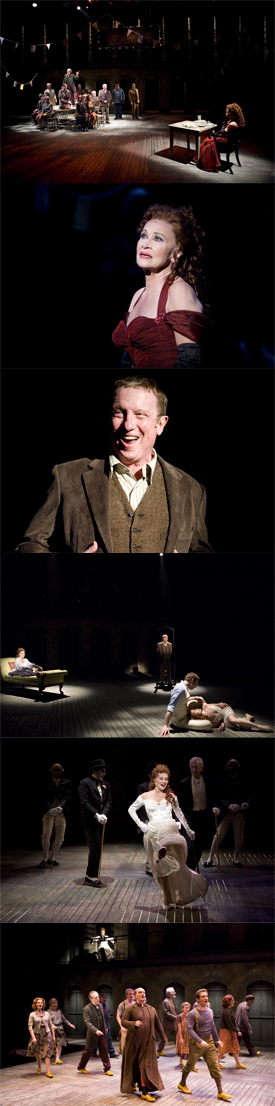

Photos of the Signature Theatre Company production of The Visit by Scott Suchman. From top to bottom: The citizens of Brachen implore Claire Zachanassian (Chita Rivera) to help them out of their dire economic plight; Rivera as Claire Zachanassian, the richest woman in the world; George Hearn as Anton Schell, the man whose poor treatment of Claire decades ago is soon to bring about his own downfall; Claire and Anton watch as their younger selves (Mary Ann Lamb and D.B. Bonds) relive a youthful moment of bliss; Claire and her entourage dance "The One-Legged Tango"; the people of Brachen sing of and dance in "Yellow Shoes," while Claire looks on.

Why are you looking all the way down here?

For more articles by Matthew Murray, click the links below!

Previous: Revisiting Life on that Wicked—and Wonderful—Stage

Next: By the Book

Or go to the Archives

[Broadway Ad Network]

[Broadway Ad Network]

If you would like to contact us, you can email us at feedback@

broadwaystars.com

[Broadway Ad Network]

[Broadway Ad Network]

- July 15: Harry Connick, Jr. in Concert on Broadway - Neil Simon

- Sept. 28: Brief Encounter - Studio 54

- Sept. 30: The Pitmen Painters - Samuel J. Friedman Theatre

- Oct. 3: Mrs. Warren's Profession - American Airlines Theatre

- Oct. 7: Time Stands Still - Cort Theatre

- Oct. 12: A Life In The Theatre - Schoenfeld Theatre

- Oct. 13: Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson - Bernard Jacobs Theatre

- Oct. 14: La Bete - The Music Box Theatre

- Oct. 21: Lombardi - Circle In The Square

- Oct. 25: Driving Miss Daisy - John Golden Theatre

- Oct. 26: Rain - A Tribute To The Beatles On Broadway - Neil Simon Theatre

- Oct. 31: The Scottsboro Boys - Lyceum Theatre

- Nov. 4: Women On The Verge Of A Nervous Breakdown - Belasco Theatre

- Nov. 9: Colin Quinn Long Story Short - Helen Hayes Theatre

- Nov. 11: The Pee-Wee Herman Show - Stephen Sondheim Theatre

- Nov. 13: The Merchant of Venice - The Broadhurst Theatre

- Nov. 14: Elf - Al Hirschfeld Theatre

- Nov. 18: A Free Man Of Color - Vivian Beaumont Theater

- Nov. 21: Elling - Ethel Barrymore Theatre

- Dec. 9: Donny & Marie: A Broadway Christmas - Marquis Theater

- Jan. 13: The Importance of Being Earnest - American Airlines Theatre

- Mar. 3: Good People - Samuel J. Friedman Theatre

- Mar. 6: That Championship Season - Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre

- Mar. 11: Kathy Griffin Wants a Tony - Belasco

- Mar. 17: Arcadia - Barrymore Theatre

- Mar. 20: Priscilla Queen Of The Desert The Musical - The Palace Theatre

- Mar. 22: Ghetto Klown - Lyceum Theatre

- Mar. 24: The Book Of Mormon - Eugene O'Neill Theatre

- Mar. 27: How To Succeed In Business Without Really Trying - Al Hirschfeld Theatre

- Mar. 31: Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo - Richard Rodgers Theatre

- Apr. 7: Anything Goes - Stephen Sondheim Theatre

- Apr. 10: Catch Me If You Can - The Neil Simon Theatre

- Apr. 11: The Motherf**ker with the Hat - Gerald Schoenfeld Theatre

- Apr. 14: War Horse - Vivian Beaumont Theater

- Apr. 17: Wonderland: A New Alice. A New Musical Adventure. - Marquis Theatre

- Apr. 19: High - Booth Theatre

- Apr. 20: Sister Act - The Broadway Theatre

- Apr. 21: Jerusalem - Music Box

- Apr. 24: Born Yesterday - Cort Theatre

- Apr. 25: The House of Blue Leaves - Walter Kerr Theatre

- Apr. 26: Fat Pig - Belasco Theatre

- Apr. 27: Baby It's You! - Broadhurst Theatre

- Apr. 27: The Normal Heart - Golden Theater

- Apr. 28: The People in the Picture - Studio 54

- Apr. 28: The End of The Season

- Jun. 12: The 65th Annual Tony Awards - Beacon Theatre

- June 14: Spider-Man, Turn Off The Dark - Foxwoods Theater

- June 21: Master Class - Samuel J. Friedman