Well, I'm glad I was at least somewhat prepared for the desecration of the operatic masterwork Porgy and Bess that's now on view on Broadway at the Richard Rodgers Theater, or I probably would have booed loudly during the performance and caused a scene. Interviews given by director Diane Paulus, playwright Suzan-Lori Parks, and musician Diedre L. Murray concerning their "adaptation" of this beloved work as a Broadway musical in advance of the show's pre-Broadway run at the American Repertory Theatre in Cambridge, Mass. made it clear that these women have little if any respect for the towering achievement of composer George Gershwin, librettist DuBose Heyward, and lyricist Ira Gershwin (who wrote a small percentage of the lyrics for the opera). Several nervy comments were also made by the star of the new production, four-time Tony Award winner Audra McDonald.

Stephen Sondheim, thanks be to him, fired up a controversy when he publicly called out Paulus, Parks, Murray, and McDonald for their remarks. Now that The Gershwins' Porgy and Bess, as the work was inaccurately and idiotically retitled some years ago, has opened at the Rodgers, New York audiences have the opportunity to decide for themselves whether or not the anger and concern expressed by Sondheim before he saw the production were well founded. My opinion? Probably not even in his worst nightmares could he have envisioned what has been done to what used to be one of the great masterworks of civilization.

Among the mostly positive reviews and other media coverage of the show when it played at ART, there were several articles that betrayed ignorance of both the history of Porgy and Bess and the extent of the changes that were made in the course of this "adaptation." The generally more negative notices filed by critics in conjunction with the Broadway opening evidenced greater knowledge and experience of the work, with especially insightful reviews from Anthony Tommasini of The New York Times and Martin Bernheimer of the Financial Times. Writing as someone who knows the opera almost as well as the back of my hand, my goal here is to offer something like a thorough, detailed analysis of exactly what the adapters have wrought.

For the first few moments of the production, you might think, "Maybe this isn't going to be so bad after all." The show curtain displays the original, three-word title of the work, not the infuriating new title; and the performance begins with conductor Constantine Kitsopoulos leading a reduced (but not disastrously so) orchestra through about 20 measures' worth of the thrilling orchestral introduction to the piece. But then, thanks to Diedre L. Murray, the intro morphs into a conventional, unexciting overture that includes snatches of Porgy's theme, "There's a Boat That's Leavin' Soon for New York," and the Jazzbo Brown Blues, the last of which has been cut from the show proper.

The show curtain rises to reveal a set (designed by Riccardo Hernandez) so ugly that it has been deplored even by those who have enjoyed this production overall. Instead of a teeming courtyard representing the vital community of Catfish Row, we see an ill-defined locale that looks something like the inside of a large storage shed. Nikki Renee Daniels begins a lovely rendition of the lullaby "Summertime" -- and then she's joined by her husband, Jake, in singing to their baby. Having Jake butt in here is a blunder in two respects: (1) "Summertime" is Clara's one shining moment in Porgy and Bess, and the focus should be on her alone throughout the song; (2) Jake's later attempt to calm the crying child with the jaunty ditty "A Woman is a Sometime Thing" is supposed to be an amusing contrast to Clara's soothing ballad, so bringing him into "Summertime" dulls the point.

As the action proceeds, it becomes all too clear that a huge amount of material -- I would guesstimate about 40 percent -- has been cut from the opera outright. The sung dialogue sections in Porgy and Bess as written are some of the most musically and dramatically effective in the work. In several previous presentations, including the first Broadway revival and the 1959 film version, the music was cut from many of these sections and the text was delivered as spoken dialogue -- as it was in the DuBose and Dorothy Heyward play Porgy, on which the opera was based. But The Gershwins' Porgy and Bess goes further in offering new spoken dialogue, penned by Suzan Lori-Parks, that in no way improves on what Heyward wrote. So why hire someone to write new lines? Sorry, but an answer to that question would involve a discussion of racial and gender politics that I'm not prepared to get into.

Ironically, in view of the new title, this adaptation also discards George Gershwin's brilliant orchestrations in favor of unworthy new ones by William David Brohn and Christopher Jahnke. The original choral arrangements have been messed with as well -- a pity, because it certainly sounds like this ensemble could have sung "Gone, Gone, Gone," "Overflow," "Leavin' for the Promised Land," and other magnificent pieces as they were originally conceived. (It's telling that I could find no credit for the new choral arrangements in the Playbill.)

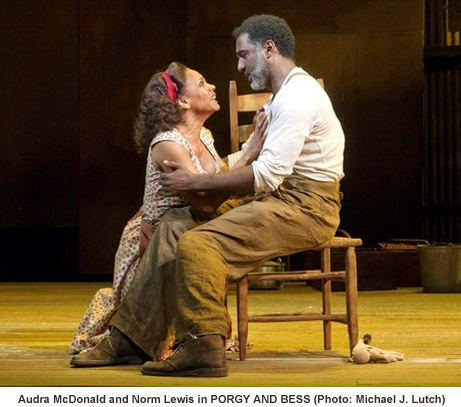

The performances of Norm Lewis as Porgy and Audra McDonald as Bess are willfully off the mark; both are playing characters markedly different from those created by Heyward and the Gershwins, and they're performing in a style appropriate to a gritty, slice of life indie film by a contemporary director rather than the more stylized and (if you will) romanticized manner that suits musical theater and opera. Lewis's Porgy is so surly that he fails to engender any sympathy at all, a far cry from the good-natured life force that this crippled beggar was meant to be. When Lewis sings the moving interlude "Nighttime, daytime," he sounds angry rather than lonely, so the audience is left dry-eyed. He doesn't even crack a smile until Scene 3, and then only because -- wait for it! -- Porgy has finally gotten laid. And with the excision of "God got plenty of money for the saucer" and other passages in which Porgy used to express his faith and inspire his friends, the character no longer reads as one of the community's spiritual bulwarks.

Despite what you may have read and heard everywhere else, McDonald as Bess gives what is in my opinion a tremendously self-indulgent, off-putting performance marked by lots of mumbling and twitching. Here we have a physically and emotionally battered woman who never seems truly happy during the course of the proceedings, not even when she's living in conjugal bliss with Porgy. There's no arc to the character, and as a result, the story becomes dull and uninteresting. (Could you ever have imagined those adjectives being applied to Porgy and Bess?) Equally sad is the fact that both McDonald and Lewis make hash of much of their music by singing it in what they presumably view as a less operatic, more "realistic" fashion, with lots of added rests, loose note values, and quirky pop/jazz phrasing that removes any sense of line or legato from Gershwin's score. One of the worst moments of the evening is "I Got Plenty of Nothing" [sic], in which Lewis annoyingly shifts back and forth between octaves every four measures and thereby sabotages one of the most joyous songs ever written for the American musical theater.

Nearly all of the other characters fare poorly as well, due to a combination of inept rewriting and misinterpretation. In the plum role of Sportin' Life, David Alan Grier is overtly nasty rather than faux-charming in an oily way, and he walks with an exaggerated strut that makes it look for all the world like his body is twisted as badly as Porgy's. Serena's lament "My Man's Gone Now," usually a show-stopper, goes for next to nothing as sung by Bryonha Marie Parham through no fault of her own, but rather because the key is wrong for her voice and the new arrangement and orchestrations are awful. In this bad-dream version of Porgy and Bess, only Phillip Boykin's Crown and NaTasha Yvette Williams' Maria are fully satisfying -- because the performances are so strong and, just as importantly, because their material was less severely futzed with by the adapters.

A full catalogue of this production's infelicities is beyond me, but please let me cite a few more. Now that there is so much spoken dialogue among the black characters, gone is the highly effective conceit of the original opera in which only the few white characters spoke rather than sang. Because there are no blackouts between scenes in this production, we get no sense of the passage of time. While the confrontation scene between Bess and Crown on Kittiwah Island is the strongest in the show (because it's performed pretty much as originally written), the climax is a shocker, and not in a good way: Bess at first fights off the violent Crown's sexual advances, but she eventually gives in and then assumes the role of aggressor, egging him on to screw her in the underbrush with exhortations of "Come on! Come on!" This may have been intended as a new interpretation in which the woman "takes ownership" of being raped, but...let's just say that it doesn't work, and leave it at that.

Many more random idiocies of staging and rewriting dot this production. When Bess returns from Kittiwah in a mentally deranged state (which makes no sense if she wasn't raped), she is put to bed in the middle of the courtyard. In the original version of the opera, Jake and the entire crew of his fishing boat are lost at sea in a hurricane; here, just as the storm begins, the crew members return to Catfish Row and explain that "Jake sent us back." (Really? On what boat?) When Porgy kills Crown, he does so not by strangling him with his powerful arms and hands but by sticking him with Mariah's knife, thereby implicating her in the murder (according to Sportin' Life).

Then there are inexplicable revisions to the original lyrics. Sportin' Life's remark to Bess, "I can't see for the life of me what you is hangin' round this place for" has been changed to "...what you is doin' round this place for," which is ungrammatical even by Catfish Row standards. Bess's reply, originally "I can't remember ever meetin' a nothin' what I likes less than I does you," is now "...what I likes worse that I does you." (Have you ever heard anyone say that he or she "likes someone worse" than someone else? I doubt it. The expression is never used because it makes no sense.) In "There's a Boat That's Leaving Soon for New York," Sportin' Life's repeated phrase "that's where we belong" has for some reason been changed to "that's where you belong," and the phrase "in the latest Paris styles" is now "just like the Paris styles," which doesn't scan with the music.

The egregious rethinking of Porgy and Bess by Paulus, Parks, and Murray continues right up to the end. The title of this review was inspired by that of the contrapuntal trio "Oh, Bess, Oh, Where's My Bess?" in which Porgy, back from having been hauled off to prison for questioning about the death of Crown, pleads with his friends to tell him where Bess has gone while Serena and Maria try to persuade him that's he's better off without her. Here, the opening lyrics of the trio have been changed to "Oh, Bess, I want my Bess" -- although the title is listed in the program as "Where's My Bess?" And the emotionally shattering finale of the opera, "Oh, Lord, I'm on My Way," is less than shattering in this production because of the rearrangement of the choral and orchestral parts.

In the final moments of The Gershwins' Porgy and Bess, the ugly set flies up and out of sight. (It should only have done so two and a half hours earlier.) The fly-up reveals a dark void -- or, if you prefer, a black hole, which is a perfect description of this execrable production.