[Broadway Ad Network]

[Broadway Ad Network]

TICKET / INFO

- StudentRush

- New York Show Tickets

- Givenik.com

- Telecharge.com

- Ticketmaster.com

- Group Sales Box Office

- Frugal TheaterGoer

- Broadway for Broke People

- Playbill's Rush/Lottery/SR

- Seating Charts

COMMUNITY

NEWS

- Back Stage

- Bloomberg

- Broadway.com

- BroadwayWorld

- Entertainment Weekly

- NYTheatre.com

- New York Magazine

- The New York Daily News

- The New York Post

- The New York Times

- The New Yorker

- Newsday

- NiteLife Exchange

- Playbill

- Show Business Weekly

- The Star-Ledger

- Talkin'Broadway

- TheaterMania.com

- Time Out New York

- American Theatre Magazine

- Theatre Development Fund (TDF)

- Best of Off-Broadway

- The Village Voice

- Variety

- The Wall Street Journal

- Journal News

REVIEWS

- The New York Times

- Variety

- New York Post

- NY1

- Aisle Say

- CurtainUp

- DC Theatre Scene

- Show Showdown

- Stage and Cinema

- StageGrade

- Talk Entertainment

- TotalTheater.com

- Off-Off Broadway Review

- TheaterOnline.com

- TheaterScene.net

- TheaterNewsOnline.com

WEST END

- The Stage

- 1st 4 London Theatre Tickets

- Book Your Theatre Tickets

- Compare Theatre Tickets.co.uk

- Theatre.com

- Whatsonstage.com [UK]

- ATW - London

- Musical Stages [UK]

- Albemarle of London

- Londontheatre.co.uk

- Google News

- Show Pairs

- ILoveTheatre.com

- The Official London Theatre Guide

- UK Tickets

BOSTON

CHICAGO

LA/SF

COLUMNS

- Peter Bart

- Andrew Cohen

- Ken Davenport

- Tim Dunleavy

- Peter Filichia

- Andrew Gans

- Ernio Hernandez

- Harry Haun

- Chad Jones

- Chris Jones

- James Marino

- Joel Markowitz

- Matthew Murray

- Michael Musto

- Ellis Nassour

- Tom Nondorf

- Richard Ouzounian

- Michael Portantiere

- Rex Reed

- Michael Riedel

- Frank Rizzo

- Richard Seff

- Frank Scheck

- Mark Shenton

- John Simon

- Robert Simonson

- Steve on Broadway (SOB)

- Steven Suskin

- Terry Teachout

- Theater Corps

- Elisabeth Vincentelli

- Hedy Weiss

- Matt Windman

- Linda Winer

- Matt Wolf

PODCAST

RADIO

TV

- Theater Talk

- BlueGobo.com

- Classic Arts Showcase

- American Theatre Wing Seminars

- Women in Theatre

- NY1

- WCBS [2]

- WNBC [4]

- FOX [5]

- WABC [7]

- WWOR [9]

- WPIX [11]

- Channel 13

- Hulu

- YouTube

AWARDS

- Tony Central

- Oscar Central

- Tony Awards

- Drama Desk Awards

- The Drama League Awards

- Lortel Awards

- Academy Awards

- Emmy Awards

- Grammy Awards

- GoldDerby

DATABASE

- Internet Broadway Database

- Internet Off-Broadway Database

- Internet Movie Database

- Internet Theatre Database

- Musical Cast Album Database

- [CastAlbums.org]

- Show Music on Record Database (LOC)

- CurtainUp Master Index of Reviews

- Musical Heaven

- StageSpecs.org

ROAD HOUSES

- Gammage [AZ]

- Golden Gate [CA]

- Curran [CA]

- Orpheum [CA]

- Community Center [CA]

- Civic [CA]

- Ahmanson [CA]

- Pantages [CA]

- Temple Hoyne Buell [CO]

- Palace [CT]

- Rich Forum [CT]

- Shubert [CT]

- Bushnell [CT]

- Chevrolet [CT]

- Broward Center [FL]

- Jackie Gleason [FL]

- Fox [GA]

- Civic Center [IA]

- Cadillac Palace [IL]

- Ford Center/Oriental [IL]

- The Bank of America Theatre [IL]

- Auditorium Theatre of Roosevelt University [IL]

- Kentucky Center [KY]

- France-Merrick [MD]

- Colonial [MA]

- Wilbur [MA]

- Charles [MA]

- Wang [MA]

- Wharton Center [MI]

- Whiting [MI]

- Fisher [MI]

- Masonic Temple [MI]

- Orpheum, State, and Pantages [MN]

- Fabulous Fox [MO]

- New Jersey PAC [NJ]

- Auditorium Center [NY]

- Proctors [NY]

- Shea's PAC [NY]

- BTI Center [NC]

- Blumenthal PAC [NC]

- Schuster PAC [OH]

- Playhouse Square [OH]

- Aronoff Center [OH]

- Ohio [OH]

- Victoria Theatre [OH]

- Birmingham Jefferson [OH]

- Merriam Theater [PA]

- Academy of Music [PA]

- Benedum Center [PA]

- Providence PAC [RI]

- Orpheum [TN]

- Hobby Center [TX]

- Music Hall [TX]

- Bass Hall [TX]

- Paramount [WA]

- Fox Cities PAC [WI]

- Marcus Center [WI]

- Weidner Center [WI]

FESTIVALS

- The New York International Fringe Festival

- The American Living Room Festival

- Summer Play Festival

- The New York Musical Theatre Festival

- Adirondack Theatre Festival

- NAMT: Festival of New Musicals

SPECIAL

- BC/EFA: Broadway Cares / Equity Fights AIDS

- The Actors' Fund

- Stage Directors and Choreographers Foundation

EDUCATION

- Google Shakespeare

- Actor Tips

- AACT

- ArtSearch

- Broadway Classroom

- Broadway Educational Alliance

- Camp Broadway

- Great Groups - New York Actors

- Theatre Communications Group (TCG)

- Theatre Development Fund (TDF)

- Off-Broadway Theater Information Center

UNIONS/TRADE

- AEA

- SAG

- AFTRA

- AGMA

- The League

- APAP

- Local 1

- ATPAM

- IATSE

- AFM

- AFM - Local 802

- Treasurers & Ticket Sellers Union

- DGA

- Dramatists Guild

- USA 829

- WGA, East

- WGA, West

- SSD&C

- AFL-CIO

- League of Professional Theatre Women

NYC NON-PROFITS

- Cherry Lane Theatre

- City Center

- Drama Dept.

- Ensemble Studio Theater

- Jean Cocteau Rep.

- Lark

- Lincoln Center Theater

- Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts

- Lucille Lortel Foundation

- Manhattan Theatre Club

- MCC

- Mint

- Pearl Theatre Company

- Public Theater

- Roundabout

- Second Stage

- Signature

- The Vineyard Theatre

- The York Theatre Company

REGIONAL

- Actors Theatre

- Alabama Shakespeare Festival

- Alley Theatre

- ACT

- American Musical Theatre in San Jose

- American Repertory

- Arena Stage

- Barrington Stage Company

- Bay Street Theatre

- Berkeley Rep

- Casa Manana

- Chicago Shakespeare Theater

- Cincinnati Playhouse

- CTC

- Dallas Summer Musicals

- Dallas Theater Center

- Denver Center

- George Street

- Goodman

- Guthrie

- Goodspeed

- Hartford Stage

- Hudson Stage Company

- Theatre de la Jeune Lune

- Kennedy Center

- La Jolla

- Long Wharf

- Lyric Stage

- Mark Taper Forum

- McCarter

- New Jersey Rep

- North Shore

- Old Globe

- Ordway

- Oregon Shakespeare

- Paper Mill

- Prince Music Theater

- The Rep (St. Louis)

- Sacramento Music Circus

- San Francisco Mime Troupe

- Seattle Rep

- Shakespeare Theatre Co. (DC)

- The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey

- South Coast Rep

- Steppenwolf

- Theater of the Stars (GA)

- Theater J (DC)

- Theater Under the Stars (TX)

- Trinity Rep

- Two River Theater Company

- Utah

- Victory Gardens

- Westport

- Williamstown

- Yale Rep

KEWL

Follow Spot

by Michael Portantiere

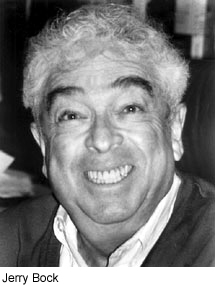

Ah, Bock!

-

I always used to say that Cy Coleman was the most underappreciated of all Broadway composers, but you know what? Now I'm thinking maybe that dubious honor goes to Jerry Bock. And it pains me to say this in the wake of Bock's death on November 3 at age 81, because I have to admit that I am -- or, rather, have been -- one of the underappreciaters.

Let me make an important distinction between "underappreciated" and "underrated." If you specifically asked me or any other musical theater enthusiast to rate Bock's scores, I'm pretty sure you'd get responses along the lines of "He's great" and "I can't think of anyone better." On the other hand, if your question were "Name the greatest composers in Broadway history," my guess is that many of us wouldn't immediately think to place Bock among the top five, and perhaps not even among the top 10, even though he definitely deserves to be in there somewhere.

There are several reasons for this, none of them having to do with the level of the man's talent. By my count, Bock wrote full scores for eight Broadway musicals, all of them in collaboration with his longtime lyricist partner Sheldon Harnick except for his first Broadway credit, Mr. Wonderful (1956). These shows collectively garnered loads of awards, and Fiorello! is one of only eight musicals to win the Pulitzer Prize for Drama. She Loves Me (1963) is a triumph of musical theater craftsmanship, and Fiddler on the Roof (1964) is an undisputed masterpiece that has been and continues to be frequently produced in countless professional and amateur productions all over the globe.

So, why is it that Jerry Bock's name doesn't necessarily leap to mind along with George Gershwin, Richard Rodgers, Frederick Loewe, Cole Porter, Jerry Herman, Stephen Sondheim, and the rest of the usual suspects who appear on lists of the greatest Broadway composers? I think there are two main reasons. First, only one Bock and Harnick musical, Fiddler on the Roof, was made into a film. I've read that there was talk of She Loves Me heading for the screen in the late 1960s, with Julie Andrews as Amalia, but sadly, it never happened. As Andrews herself once said to me, "Wouldn't that have been something!

Second reason: Because the songs that Bock wrote with Harnick are so wonderfully well integrated into their musicals and are so character-specific, they have relatively rarely been heard as stand-alone items in concerts, on TV, or on recordings, with one or two exceptions -- e.g. the title tune from She Loves Me. (Yes, it's true that many songs from Sondheim shows are also difficult to present effectively out of context because they possess this same wonderful quality of specificity, but this fact has never stopped singers or producers of revues and gala concerts from doing so.)

Last night, the marquees of all Broadway theaters were dimmed for one minute at 8pm in memory of Bock. Paul Libin, chairman of The Broadway League, described him as "one of Broadway's great composers," and stated that "his work will live forever on Broadway." To which I can only say, "Amen." Fiddler on the Roof (with a book by the great Joseph Stein, who preceded Bock in death by one week) and She Loves Me are two of the most perfect musicals ever to be created by the mind of man, and they would have assured Jerry Bock's place of prominence in the pantheon even if he had never written anything else.

********************

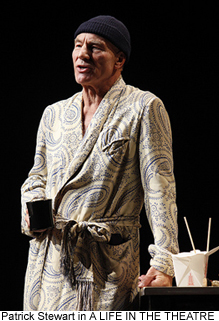

Something unusual has happened over at the revival of David Mamet's A Life in the Theatre, starring Patrick Stewart and T.R. Knight. During early previews, I heard that the scene changes in the show were very long and seemed all the longer because there was no music to accompany them. Then, as previews continued, I started to hear that the changes were happening more quickly, and also that some music had been added to cover them. So you can imagine my surprise when I saw the show a few days after its official opening and there was no music whatsoever -- only complete silence -- during the changes.

I checked the small-print production credits in the Playbill and, indeed, I found there a credit for original music by Obadiah Eaves. A few days later, I asked an in-the-business friend of mine who had also seen the show if he knew what had happened. According to this fellow, Eaves had been hired during previews to write music to cover the scene changes, had done the job very quickly, and his music was used for just this purpose at several previews -- but then it was removed "because Mamet hated it."

The removal strikes me as having been a really bad idea, and I think it was more than a little responsible for the production's mixed reviews and diffident word of mouth. Many of the scenes in A Life in the Theatre are extremely short, so transitional music would have helped (and, apparently, did help) greatly to keep the rhythm of the show going, rather than leaving all that dead space. Stewart and Knight are giving their all up there, but it's impossible to keep up the energy of the production when it's constantly interrupted by 30-second segments during which the audience sits in darkness and silence, waiting for the next thing to happen.

If it's true that Mamet is responsible for the music having been cut, I guess that shouldn't come as a huge surprise. Anyone who has read his book True or False is aware of this great playwright's controversial, simplistic theories on the art of acting. And if you look at the man's track record as a director, both on stage and in film, it seems clear that he is nowhere near as talented in this area as he in in terms of the actual writing. The most recent evidence of this was Race, in which Mamet somehow managed to elicit bland or one-note performances from three of the four cast members -- including David Alan Grier and Richard Thomas, neither of whom to my knowledge has ever before been accused of being bland or one-note.

My point is that, along with Arthur Laurents and a few other writers who attempt to direct their own material or to throw their weight around at rehearsals, Mamet would be well advised to leave the driving to others. After all, there's absolutely nothing wrong in not being multi-talented, unless you try to do it all anyway.

Published on Friday, November 5, 2010

Michael Portantiere has more than 30 years' experience as an editor and writer for TheaterMania.com, InTHEATER magazine, and BACK STAGE. He has interviewed theater notables for NPR.org, PLAYBILL, STAGEBILL, and OPERA NEWS, and has written notes for several cast albums. Michael is co-author of FORBIDDEN BROADWAY: BEHIND THE MYLAR CURTAIN, published in 2008 by Hal Leonard/Applause. Additionally, he is a professional photographer whose pictures have been published by THE NEW YORK TIMES, the DAILY NEWS, and several major websites. (Visit www.followspotphoto.com for more information.) He can be reached at [email protected]

Why are you looking all the way down here?

For more articles by Michael Portantiere, click the links below!

Previous: Bernstein and Schwartz at the Opera

Next: The Picture of Jason Danieley

Or go to the Archives

[Broadway Ad Network]

[Broadway Ad Network]

If you would like to contact us, you can email us at feedback@

broadwaystars.com

[Broadway Ad Network]

[Broadway Ad Network]

- July 15: Harry Connick, Jr. in Concert on Broadway - Neil Simon

- Sept. 28: Brief Encounter - Studio 54

- Sept. 30: The Pitmen Painters - Samuel J. Friedman Theatre

- Oct. 3: Mrs. Warren's Profession - American Airlines Theatre

- Oct. 7: Time Stands Still - Cort Theatre

- Oct. 12: A Life In The Theatre - Schoenfeld Theatre

- Oct. 13: Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson - Bernard Jacobs Theatre

- Oct. 14: La Bete - The Music Box Theatre

- Oct. 21: Lombardi - Circle In The Square

- Oct. 25: Driving Miss Daisy - John Golden Theatre

- Oct. 26: Rain - A Tribute To The Beatles On Broadway - Neil Simon Theatre

- Oct. 31: The Scottsboro Boys - Lyceum Theatre

- Nov. 4: Women On The Verge Of A Nervous Breakdown - Belasco Theatre

- Nov. 9: Colin Quinn Long Story Short - Helen Hayes Theatre

- Nov. 11: The Pee-Wee Herman Show - Stephen Sondheim Theatre

- Nov. 13: The Merchant of Venice - The Broadhurst Theatre

- Nov. 14: Elf - Al Hirschfeld Theatre

- Nov. 18: A Free Man Of Color - Vivian Beaumont Theater

- Nov. 21: Elling - Ethel Barrymore Theatre

- Dec. 9: Donny & Marie: A Broadway Christmas - Marquis Theater

- Jan. 13: The Importance of Being Earnest - American Airlines Theatre

- Mar. 3: Good People - Samuel J. Friedman Theatre

- Mar. 6: That Championship Season - Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre

- Mar. 11: Kathy Griffin Wants a Tony - Belasco

- Mar. 17: Arcadia - Barrymore Theatre

- Mar. 20: Priscilla Queen Of The Desert The Musical - The Palace Theatre

- Mar. 22: Ghetto Klown - Lyceum Theatre

- Mar. 24: The Book Of Mormon - Eugene O'Neill Theatre

- Mar. 27: How To Succeed In Business Without Really Trying - Al Hirschfeld Theatre

- Mar. 31: Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo - Richard Rodgers Theatre

- Apr. 7: Anything Goes - Stephen Sondheim Theatre

- Apr. 10: Catch Me If You Can - The Neil Simon Theatre

- Apr. 11: The Motherf**ker with the Hat - Gerald Schoenfeld Theatre

- Apr. 14: War Horse - Vivian Beaumont Theater

- Apr. 17: Wonderland: A New Alice. A New Musical Adventure. - Marquis Theatre

- Apr. 19: High - Booth Theatre

- Apr. 20: Sister Act - The Broadway Theatre

- Apr. 21: Jerusalem - Music Box

- Apr. 24: Born Yesterday - Cort Theatre

- Apr. 25: The House of Blue Leaves - Walter Kerr Theatre

- Apr. 26: Fat Pig - Belasco Theatre

- Apr. 27: Baby It's You! - Broadhurst Theatre

- Apr. 27: The Normal Heart - Golden Theater

- Apr. 28: The People in the Picture - Studio 54

- Apr. 28: The End of The Season

- Jun. 12: The 65th Annual Tony Awards - Beacon Theatre

- June 14: Spider-Man, Turn Off The Dark - Foxwoods Theater

- June 21: Master Class - Samuel J. Friedman