Two Nights at the Opera, and One Night at the Pop-Operetta

Is there anything scarier than a nasty, vindictive teenage girl who can't get what she wants? This sort of character has appeared regularly on stage, film, television, and in literature, perhaps most famously of all in the Oscar Wilde drama Salome and the equally horrifying Richard Strauss opera based on the play. When I experienced Karita Mattila as Salome at the Metropolitan Opera a few years ago, I thought it one of the most thrilling operatic performances I had ever witnessed; so I'm pleased to tell you that the lady was equally amazing when she returned to the role on the second night of the Met's current season.

Brilliant in every major and minor detail is Mattila's portrayal of this very sick young woman, whose sexual rejection by John the Baptist -- here called Jochanaan -- sends her into such a fury that she demands the prophet be killed and that his severed head be handed to her on a silver platter. (I particularly enjoyed the moment when Mattila's Salome unfeelingly kicked aside the dead hand of Narraboth, the young captain of the palace guard, who had just committed suicide for unrequited love of her.) Beautiful and curvaceous, Mattila is supremely sexy in the Dance of the Seven Veils -- one part of which might well be retitled the Lap Dance of the Seven Veils, given the way it's performed here. Oh, and she sings the hell out of the role in a gleaming, expertly controlled soprano that's sharply focused as a laser beam.

Mattila is well partnered in the current revival by Met debutant Juha Uusitalo; his Jochanaan is a major vocal and dramatic force to be reckoned with, even if the baritone hardly appears "wasted" as specified by the libretto. Kim Begley is terrific as the repulsive Herod, one of the few operatic roles for which acting talent is more important than vocal prowess - not that the tenor is lacking in this respect. Ildiko Komlosi overindulges in arm and hand motions as Herodias, but Joseph Kaiser and Lucy Schaufer are excellent as Narraboth and the page who adores him.

Led by Patrick Summers, the Met Orchestra plays the score magnificently, from the most delicate, chamber-like sections to those that require huge torrents of scarifying sound. Jurgen Flimm's production, with sets and costumes by Santo Loquasto, effectively presents the opera in "a non-specific modern setting" rather than in ancient Galilee. ("It sort of looks like Dubai," remarked my companion.) But James F. Ingalls unfocused lighting is a detriment to this generally fine staging, especially in the opera's breathtaking final moments.

******

I've been attending performances at the Metropolitan Opera since the mid '70s, and La Gioconda has not been absent from the repertoire during that period. Still, this opera by the one-hit-wonder Amilcare Ponchielli is mounted far less often than the masterpieces of Verdi, Puccini, Mozart, Wagner, etc., which partly explains why I had never heard it performed live until I caught up with it at the Met last week.

There are three main reasons why Gioconda has only a tenuous foothold on the standard repertoire. First of all, the plot is patently ridiculous, with countless examples of characters behaving in ways that have no basis in psychological reality. (If you were a guy who wanted to hook up with a hot dame, would you try to achieve your goal by denouncing her blind mother as a witch and urging the public to off the old lady? That's just what the spy Barnaba does in Gioconda, and the natural response of the audience is utter incredulity.)

Further, though much of the opera's music is lovely, it's not so great that it completely outweighs the infelicities of the libretto, as is the case with Il Trovatore and several other important works. Finally, as Roland Graeme notes in the indispensable Metropolitan Opera Guide to Recorded Opera, "Most recordings [of La Gioconda] have foundered on the basic necessity of assembling no fewer than six major singers, one in each vocal category." This obviously applies to live performances as well, making the opera quite a challenge to get right.

If the Met's current presentation of Gioconda doesn't feature "six major singers," it does give us at least three, all of them in the leading women's roles. Soprano Deborah Voigt (Gioconda) remains a world-class singer -- even if, in the wake of her huge weight loss, her voice has also become somewhat leaner and her pitch is not longer always 100% rock solid. Mezzo Olga Borodina (Laura) sounds as beautiful as she looks, and Ewa Podles sings La Cieca's music in a true contralto voice so rich and expressive that her Act I aria earned a major ovation.

Tenor Aquiles Machado is something of a disappointment as Enzo Grimaldo, displaying a basically warm and sturdy voice that begins to sound rather constricted and wobbly when pressure is applied. But baritone Jason Stearns acquitted himself most honorably in subbing for an indisposed Carlo Guelfi as Barnaba at the matinee performance on Saturday, September 27, while bass Orlin Anastassov sings sonorously and cuts a fine figure as Alvise.

Daniele Callegari, a conductor previously unknown to me, is in full control of the orchestra. The production -- originally directed by Margherita Wallman, with sets and costumes by Beni Montresor -- dates from 1966, the Met's first season in its second home at Lincoln Center. Recently restored, it's handsome in the typical, heightened-realism style of that era, and it serves as an interesting artifact of how operas looked at the Met way back when.

The show has been spiffed up with new choreography this season: Christopher Wheeldon has created a marvelous Dance of the Hours, featuring brilliant star turns by Letizia Giuliani and Angel Corella. Unfortunately, no stage director or choreographer seems to have given much attention to the chorus members: They file on stage to stand and sing lustily in clumps, only to file dutifully off and on again and again, singing and clumping like the ensemble of the "Pleasant Peasant" operetta in that hilarious I Love Lucy episode.

********

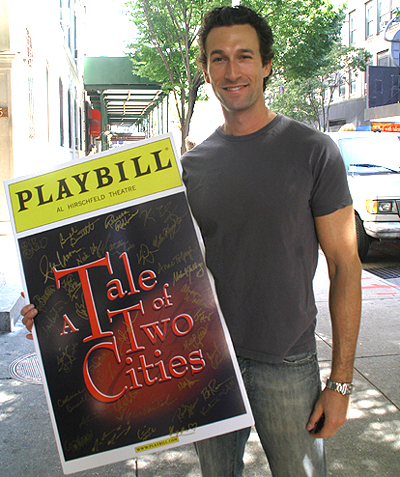

If I may borrow a phrase that has been used in Forbidden Broadway in a different context, I'd like to tell you that A Tale of Two Cities is "less miserable" than you've been led to believe. To put it another way, with a paraphrase from the Charles Dickens novel on which the musical is based, the show is far, far better than you would ever expect it to be after reading the outright toxic reviews that have greeted its opening .

Don't get me wrong: Jill Santoriello's score for ATOTC doesn't even approach the level of achievement attained by our best musical theater writers. Her work is undistinguished and highly derivative, though aside from one melody that's too close for comfort to Rodgers and Hart's "I Could Write a Book," it's generally rather than specifically familiar-sounding. But aside from a number for Madame DeFarge that's jarringly anachronistic in style, none of Santoriello's music can be described as actively "bad" -- and the same can be said of her lyrics. For what it's worth, this score is notably superior to what Claude-Michel Schoenberg and Alain Boublil wrought for Miss Saigon, a show that gained lots of fans and ran on Broadway for five years.

Santoriello also deserves great credit for having the good sense to realize that A Tale of Two Cities should be an old-fashioned book musical, rather than yet another sung-through pop-operatic monstrosity. Purely in terms of clarity and effectiveness of the storytelling, her adaptation of Dickens is far more successful that Boublil and Schoenberg's adaptation of Victor Hugo's Les Misérables -- though it must be said that Santoriello's task was much easier, since the Dickens novel is only about one-third as long as the Hugo tome.

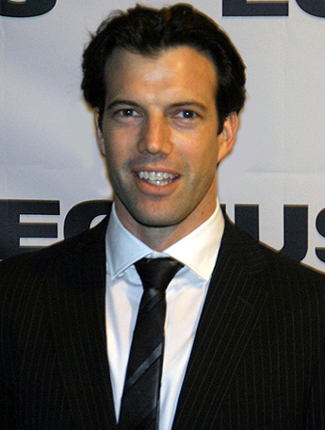

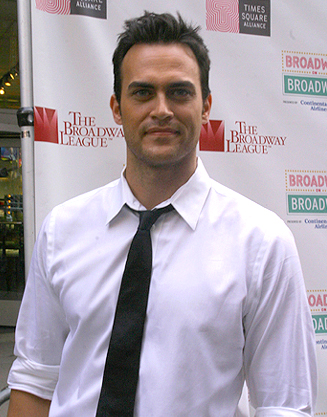

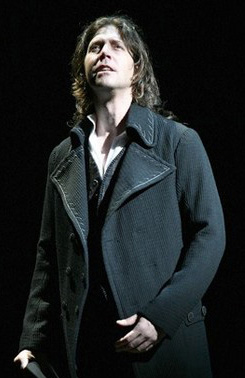

A very strong cast, led by James Barbour in a superb performance as Sydney Carton, helps to keep this show from feeling like a flop. Other standouts in the company include Brandi Burkhardt as Lucie Manette, Gregg Edelman as her father, and Aaron Lazar as Charles Darney. The fact that Barbour and Lazar possess two of the most beautiful voices on Broadway should be recommendation enough to see (and hear) this show.

If nothing else, Jill Santoriello's A Tale of Two Cities shows us what a great musical Dickens' novel might have inspired if the composer-lyricist-librettist had risen fully to the occasion -- or if the adaptation had been done by a person or team with more innate talent and skill, such as Stephen Flaherty and Lynn Ahrens at their best. Had the show been directed by someone more experienced than Warren Carlyle, heretofore known as a choreographer, that person would presumably have told Santoriello "these four songs need to be rewritten" and "those three songs have got to go." Chalk it all up as a missed opportunity.