WHAT HUMP(ERDINCK)?

"Freakish" is the word that a friend of mine used to describe the Richard Jones-John Macfarlane production of Engelbert Humperdinck's Hansel and Gretel, which he caught in San Francisco a few years ago. I was determined to keep an open mind when I saw the production at the Metropolitan Opera, where it's now playing in repertory; but I have to say that my friend's adjective will do as well as any for what the director and designer have wrought.

Though Jones has many credits in opera and theater, I'll always remember him for having misdirected the Broadway musical Titanic. One of his many weird decisions in that show was to cast an adult woman in the role of the young bellboy who greets the ship's passengers just before sailing. This must have been done to make some profound point that escaped me and, I suspect, the rest of the audience, but the actual result was to render insufferable a character who should have been charming. While there is one piece of cross-gender casting in Jones' Hansel and Gretel, it's traditional and it works; but the production is chock-full of other wild ideas that have little to do with the work we all know and love.

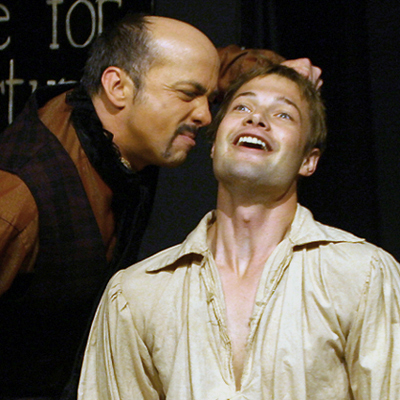

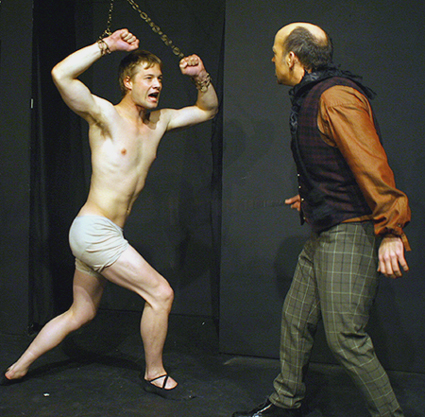

As written by composer Humperdinck and librettist Adelheid Wette (his sister), rather loosely based on the classic fairy tale as retold by the brothers Grimm, the opera tells of two impoverished siblings who become hopelessly lost in the forest when they are sent by their distraught mother to pick strawberries. The next morning, Hansel and Gretel encounter a witch living in a gingerbread house. The old hag plans to devour the children, but they outwit her, and she comes to a bad end in her own oven. Then Hansel and Gretel break the magic spell that the witch had used to turn a passel of other children into gingerbread. Reunited with their parents, H&G presumably live happily ever after.

In the Met production, the picturesque cottage in which Hansel and Gretel live with their folks is represented by a cramped, dingy, mid-20th century kitchen, complete with old-style fridge, sink, and cupboards. The kids' father is a drunken wife-abuser, and their mother -- who bears a striking resemblance to Christine Baranski as depicted here -- pops pills. Things get worse in Act II, set in a German Expressionist dining room with leafy trees on the wallpaper springing from headless human trunks; and in Act III, no longer a gingerbread dwelling but instead a rusty, dirty, industrial kitchen wherein the witch putters about, looking for all the world like Julia Child on steroids.

Jones' direction and Macfarlane's set and costume designs contradict the libretto at nearly every turn. Multiple references to the children being outdoors in the second and third scenes remain, even though the sets are interiors; in Act III, the witch sings about riding her broomstick as usual, but all she does during this sequence is cook; and so on. Hansel and Gretel is performed here in an infelicitous translation by David Pountney. Given the great difficulty experienced by singers in trying to project English text in the cavernous Met, you'll only catch a small percentage of the lines, but the company's titling system makes it obvious that what's supposed to happen in the opera and what actually happens at the behest of the director and designer are largely unrelated.

This is one of those annoying productions in which the subtext of the work is played on the top, with all the sublety of a sumo wrestler wielding a sledgehammer. Jones is correct in noting that images of food and hunger run through Hansel and Gretel, which explains the kitchen/dining room sets and the fact that Hansel and Gretel dream of having a huge meal served to them by 14 chefs, rather than of being guarded in their slumber by 14 angels. But the opera is not ONLY about hunger, so to stress this above all else is a reductive approach. Many of the stage images in this production are inarguably arresting, yet they fail to illuminate the material. (After all, if some director were to have a spaceship land on stage during the final scene of Rigoletto, that would be visually stunning, but it would tell us more about the director's ego than about Verdi's opera.)

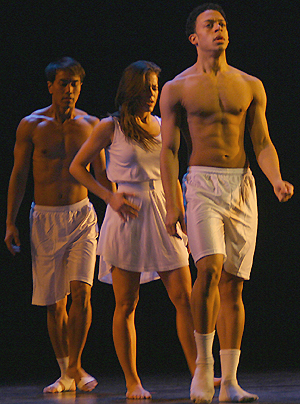

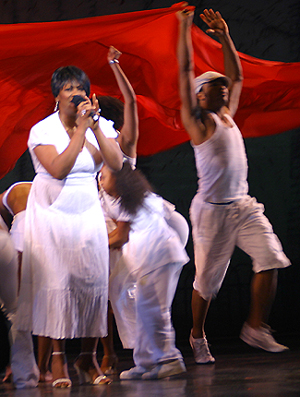

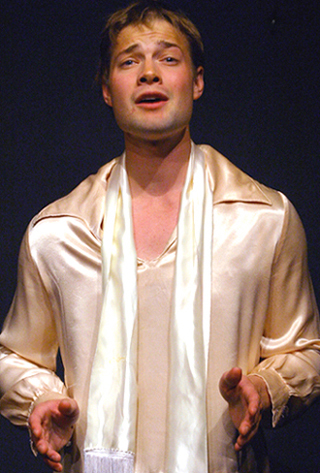

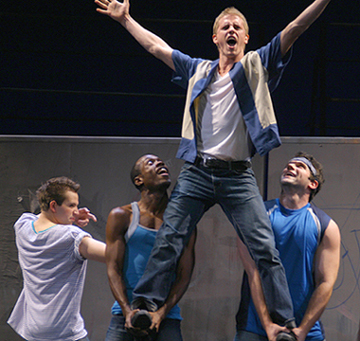

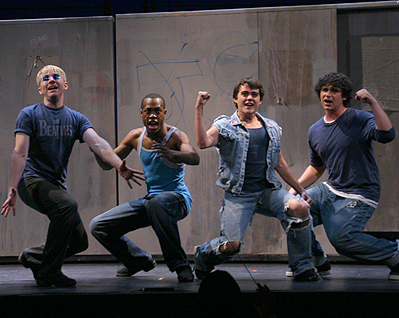

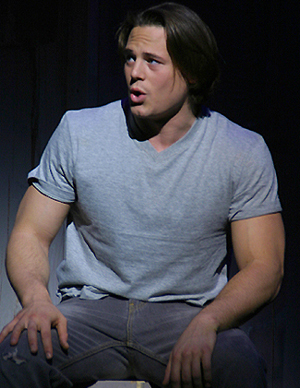

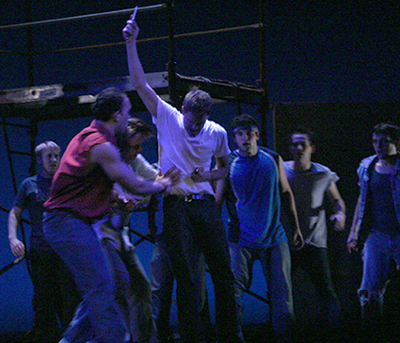

While all of the above and much more weirdness was happening during the matinee on Saturday, December 29, a wonderful performance of the score was taking place. Mezzo Alice Coote and soprano Christine Schäfer possess just the right vocal timbre for Hansel and Gretel, and they have the characters' pre-adolescent body language down pat. Individually and as a team, they're utterly delightful. Alan Held and Rosalind Plowright are well cast as parents Peter and Gertrude, while Philip Langridge seems to be having the time of his life as the witch. Sasha Cooke displays a beautiful soprano in the role of the Sandman (it's not her fault that she has been costumed and made-up to look like Nosferatu), and Lisette Oropesa does likewise as the Dew Fairy (here a rubber-gloved maid who cleans up after the childrens' dream feast). Conductor Vladimir Jurowski fully communicates the score's grandeur without ever making it sound heavy-handed.

If only the direction and design matched the music making in quality. Family-friendly entertainment is big business during the holiday season in NYC, so it's no surprise that the Met was packed for Hansel and Gretel. But I can't help wishing that the company's new general manager, Peter Gelb, had kept the lovely, 40-year-old Nathaniel Merrill/Robert O'Hearn production of the opera in the repertoire for a few more seasons and worked his marketing magic upon it, rather than bringing Richard Jones and John Macfarlane's ultimately silly production to the Met stage.