LUCIA GOES MAD, GETS EVEN AT MET

Men are selfish pigs who tend to treat women like property. This is a major point of both Donizetti's Lucia di Lammermoor and Puccini's Madama Butterfly, the masterworks that respectively served as the Metropolitan Opera's season openers this year and last. Director Mary Zimmerman's take on Lucia, unveiled at the Met on September 24, makes the point very clearly.

If you consider Zimmerman's Metamorphoses to have been one of the supreme highlights of your theatrical experience, as I do, chances are that you've already secured a ticket to Lucia. You'll be glad you did. This exploration of the central character's madness, the result of the poor Scottish lass being forced to renounce her lover and marry another man for political/financial reasons, is astute and gripping. Early in the action, the appearance of a ghost -- referred to in Salvatore Cammarano's libretto based on the novel by Sir Walter Scott, but not usually seen -- brings home the fact that the mistreatment of women in a patriarchal society is a tragedy destined to be repeated again and again. (This may partly explain Zimmerman's having updated the opera's action from the 17th century to the mid 1800s, a choice that neither helps nor harms the story.)

Throughout the production, there are dozens of felicitous directorial touches. In the scene where the guests are gathered to witness the signing of the wedding contract, Lucia's brother Enrico announces her arrival to her bridegroom and fidgets nervously until she shows up; then he none-too-subtly strong-arms her as he mutters sotto-voce that she'd better behave if she doesn't want to ruin him. At one point during Lucia's mad scene, she gets the giggles. Oh, and in the final scene, the death of Edgardo is depicted as an assisted suicide. (I'll say no more!)

The major fly in the ointment here is the set design of Daniel Ostling -- odd, since he was responsible for the gorgeous, evocative, pool-based unit set for Metamorphoses. In Lucia, his mixture of representational settings (e.g., the woods of Act I) with far less realistic elements is distracting; we spend so much time trying to figure out what he's going for that we're taken out of the drama. For the oft-omitted Wolf's Crag scene that begins Act III, Ostling provides virtually no set at all. Is it possible that this scene was going to be cut as usual until a last minute decision resulted in its inclusion?

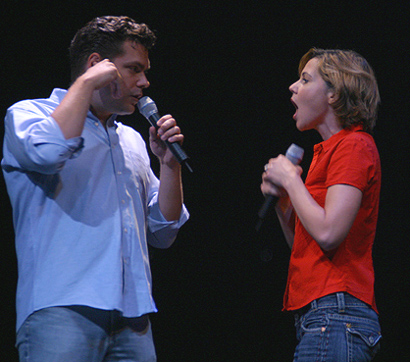

To some extent, this lack of a cohesive style is reflected in the direction, which is founded in psychological realism but occasionally veers off that path. Why, for example, do the chorus members suddenly begin to move in a slow-motion, ritualistic way during Lucia's mad scene? Still, Zimmerman has come up with many bracing ideas, several of them involving the brilliant Natalie Dessay as Lucia. For one thing, these two have managed to find some moments of joy and lightness in this grim piece, as in Lucia's scene with her companion Alisa and the surreptitious rendezvous between Lucia and her lover, Edgardo.

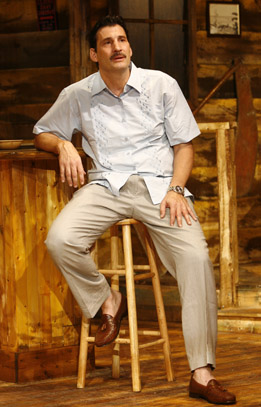

With her big eyes, sweet face, and lithe figure, Dessay is an uncommonly lovely Lucia -- and the fact that Mariusz Kwiecien as her bullying brother Enrico is also a looker causes their onstage confrontations to be fraught with an incestuous sexual tension. (I loved the moment when, immediately after berating Lucia, her brother grabbed her and almost violently kissed her on the forehead.) Vivid portrayals are also offered by Michaela Martens as Alisa; Stephen Costello as Arturo, the bridegroom who comes to a gruesome end; and John Relyea as the priest Raimondo, whose misguided efforts to avert the tragedy that's waiting to happen only serve to help bring it on.

From a musical standpoint, this Lucia is near perfect. James Levine, not famous as a bel canto specialist, conducts a virile performance that nevertheless sacrifices nothing in terms of tenderness and lyricism. The celebrated sextet, intriguingly staged by Zimmerman as a photo op (!), is even more of a guaranteed show-stopper than usual. Dessay is a wonder, delivering gorgeous, long-lined phases or dazzling coloratura even while lying flat on her back or being dragged upstage. Her mad scene is riveting, whether she's knocking out a stratospheric high note or letting loose with a gut-wrenching scream.

All of the other principals are superb with the exception of Marcello Giordani, miscast as Edgardo both vocally (his voice is too muscular, not quite lyrical enough for this music) and physically. Though he's unbeatable in parts well suited to his gifts -- the title role in Andrea Chenier, Des Grieux in Manon Lescaut, even Pinkerton in Butterfly -- Giordano is no Edgardo.

Mara Blumenfeld's costumes in the style of the production's rather unspecific 19th century time frame are eye catching, and T.J. Gerckens' lighting is more consistent than Ostling's sets. The Met orchestra plays beautifully, natch, and the chorus sings lustily. For all its flaws, this Lucia is an unforgettable three hours of music drama.