[Advertisement]

[Advertisement]

TICKET / INFO

- StudentRush

- New York Show Tickets

- Givenik.com

- Telecharge.com

- Ticketmaster.com

- Group Sales Box Office

- Frugal TheaterGoer

- Broadway for Broke People

- Playbill's Rush/Lottery/SR

- Seating Charts

COMMUNITY

NEWS

- Back Stage

- Bloomberg

- Broadway.com

- BroadwayWorld

- Entertainment Weekly

- NYTheatre.com

- New York Magazine

- The New York Daily News

- The New York Post

- The New York Times

- The New Yorker

- Newsday

- NiteLife Exchange

- Playbill

- Show Business Weekly

- The Star-Ledger

- Talkin'Broadway

- TheaterMania.com

- Time Out New York

- American Theatre Magazine

- Theatre Development Fund (TDF)

- Best of Off-Broadway

- The Village Voice

- Variety

- The Wall Street Journal

- Journal News

REVIEWS

- The New York Times

- Variety

- New York Post

- NY1

- Aisle Say

- CurtainUp

- DC Theatre Scene

- Show Showdown

- Stage and Cinema

- StageGrade

- Talk Entertainment

- TotalTheater.com

- Off-Off Broadway Review

- TheaterOnline.com

- TheaterScene.net

- TheaterNewsOnline.com

WEST END

- The Stage

- 1st 4 London Theatre Tickets

- Book Your Theatre Tickets

- Compare Theatre Tickets.co.uk

- Theatre.com

- Whatsonstage.com [UK]

- ATW - London

- Musical Stages [UK]

- Albemarle of London

- Londontheatre.co.uk

- Google News

- Show Pairs

- ILoveTheatre.com

- The Official London Theatre Guide

- UK Tickets

BOSTON

CHICAGO

LA/SF

COLUMNS

- Peter Bart

- Andrew Cohen

- Ken Davenport

- Tim Dunleavy

- Peter Filichia

- Andrew Gans

- Ernio Hernandez

- Harry Haun

- Chad Jones

- Chris Jones

- James Marino

- Joel Markowitz

- Matthew Murray

- Michael Musto

- Ellis Nassour

- Tom Nondorf

- Richard Ouzounian

- Michael Portantiere

- Rex Reed

- Michael Riedel

- Frank Rizzo

- Richard Seff

- Frank Scheck

- Mark Shenton

- John Simon

- Robert Simonson

- Steve on Broadway (SOB)

- Steven Suskin

- Terry Teachout

- Theater Corps

- Elisabeth Vincentelli

- Hedy Weiss

- Matt Windman

- Linda Winer

- Matt Wolf

PODCAST

RADIO

TV

- Theater Talk

- BlueGobo.com

- Classic Arts Showcase

- American Theatre Wing Seminars

- Women in Theatre

- NY1

- WCBS [2]

- WNBC [4]

- FOX [5]

- WABC [7]

- WWOR [9]

- WPIX [11]

- Channel 13

- Hulu

- YouTube

AWARDS

- Tony Central

- Oscar Central

- Tony Awards

- Drama Desk Awards

- The Drama League Awards

- Lortel Awards

- Academy Awards

- Emmy Awards

- Grammy Awards

- GoldDerby

DATABASE

- Internet Broadway Database

- Internet Off-Broadway Database

- Internet Movie Database

- Internet Theatre Database

- Musical Cast Album Database

- [CastAlbums.org]

- Show Music on Record Database (LOC)

- CurtainUp Master Index of Reviews

- Musical Heaven

- StageSpecs.org

ROAD HOUSES

- Gammage [AZ]

- Golden Gate [CA]

- Curran [CA]

- Orpheum [CA]

- Community Center [CA]

- Civic [CA]

- Ahmanson [CA]

- Pantages [CA]

- Temple Hoyne Buell [CO]

- Palace [CT]

- Rich Forum [CT]

- Shubert [CT]

- Bushnell [CT]

- Chevrolet [CT]

- Broward Center [FL]

- Jackie Gleason [FL]

- Fox [GA]

- Civic Center [IA]

- Cadillac Palace [IL]

- Ford Center/Oriental [IL]

- The Bank of America Theatre [IL]

- Auditorium Theatre of Roosevelt University [IL]

- Kentucky Center [KY]

- France-Merrick [MD]

- Colonial [MA]

- Wilbur [MA]

- Charles [MA]

- Wang [MA]

- Wharton Center [MI]

- Whiting [MI]

- Fisher [MI]

- Masonic Temple [MI]

- Orpheum, State, and Pantages [MN]

- Fabulous Fox [MO]

- New Jersey PAC [NJ]

- Auditorium Center [NY]

- Proctors [NY]

- Shea's PAC [NY]

- BTI Center [NC]

- Blumenthal PAC [NC]

- Schuster PAC [OH]

- Playhouse Square [OH]

- Aronoff Center [OH]

- Ohio [OH]

- Victoria Theatre [OH]

- Birmingham Jefferson [OH]

- Merriam Theater [PA]

- Academy of Music [PA]

- Benedum Center [PA]

- Providence PAC [RI]

- Orpheum [TN]

- Hobby Center [TX]

- Music Hall [TX]

- Bass Hall [TX]

- Paramount [WA]

- Fox Cities PAC [WI]

- Marcus Center [WI]

- Weidner Center [WI]

FESTIVALS

- The New York International Fringe Festival

- The American Living Room Festival

- Summer Play Festival

- The New York Musical Theatre Festival

- Adirondack Theatre Festival

- NAMT: Festival of New Musicals

SPECIAL

- BC/EFA: Broadway Cares / Equity Fights AIDS

- The Actors' Fund

- Stage Directors and Choreographers Foundation

EDUCATION

- Google Shakespeare

- Actor Tips

- AACT

- ArtSearch

- Broadway Classroom

- Broadway Educational Alliance

- Camp Broadway

- Great Groups - New York Actors

- Theatre Communications Group (TCG)

- Theatre Development Fund (TDF)

- Off-Broadway Theater Information Center

UNIONS/TRADE

- AEA

- SAG

- AFTRA

- AGMA

- The League

- APAP

- Local 1

- ATPAM

- IATSE

- AFM

- AFM - Local 802

- Treasurers & Ticket Sellers Union

- DGA

- Dramatists Guild

- USA 829

- WGA, East

- WGA, West

- SSD&C

- AFL-CIO

- League of Professional Theatre Women

NYC NON-PROFITS

- Cherry Lane Theatre

- City Center

- Drama Dept.

- Ensemble Studio Theater

- Jean Cocteau Rep.

- Lark

- Lincoln Center Theater

- Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts

- Lucille Lortel Foundation

- Manhattan Theatre Club

- MCC

- Mint

- Pearl Theatre Company

- Public Theater

- Roundabout

- Second Stage

- Signature

- The Vineyard Theatre

- The York Theatre Company

REGIONAL

- Actors Theatre

- Alabama Shakespeare Festival

- Alley Theatre

- ACT

- American Musical Theatre in San Jose

- American Repertory

- Arena Stage

- Barrington Stage Company

- Bay Street Theatre

- Berkeley Rep

- Casa Manana

- Chicago Shakespeare Theater

- Cincinnati Playhouse

- CTC

- Dallas Summer Musicals

- Dallas Theater Center

- Denver Center

- George Street

- Goodman

- Guthrie

- Goodspeed

- Hartford Stage

- Hudson Stage Company

- Theatre de la Jeune Lune

- Kennedy Center

- La Jolla

- Long Wharf

- Lyric Stage

- Mark Taper Forum

- McCarter

- New Jersey Rep

- North Shore

- Old Globe

- Ordway

- Oregon Shakespeare

- Paper Mill

- Prince Music Theater

- The Rep (St. Louis)

- Sacramento Music Circus

- San Francisco Mime Troupe

- Seattle Rep

- Shakespeare Theatre Co. (DC)

- The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey

- South Coast Rep

- Steppenwolf

- Theater of the Stars (GA)

- Theater J (DC)

- Theater Under the Stars (TX)

- Trinity Rep

- Two River Theater Company

- Utah

- Victory Gardens

- Westport

- Williamstown

- Yale Rep

KEWL

[Advertisement]

Can dramatic license be stretched too far? That's the question my friend and colleague Adam Feldman of Time Out New York asked in his Friday column about Dan Gordon's new Broadway play, Irena's Vow. He raises a number of interesting issues, but I'm not sure he goes far as he could in addressing the issue and its implications for theatre audiences and artists alike.

Can dramatic license be stretched too far? That's the question my friend and colleague Adam Feldman of Time Out New York asked in his Friday column about Dan Gordon's new Broadway play, Irena's Vow. He raises a number of interesting issues, but I'm not sure he goes far as he could in addressing the issue and its implications for theatre audiences and artists alike.

He contends that the play, which chronicles how a Polish-Catholic woman named Irena Gut Opdyke (played onstage by Tovah Feldshuh) saved 13 Jews from extermination during World War II by hiding them in the cellar of a prominent Nazi major, sacrifices both historical accuracy and theatrical viability by its treatment of the subject. In particular, he references one scene in which one of the hiding Jewish couples is giving birth to their son during a party the major is holding—a scene that, according to Opdyke's own memoir, never truly happened. He concludes:

...the problem with Irena's Vow's continual falsification is that it calls into question the veracity of everything else in the story. What else in the play is made up? What else is true? Most historical plays, of course, fudge their material to some extent, and Irena's Vow makes no explicit claim to complete accuracy. But this is a docudrama-style play about the Holocaust, and its point...is that we must believe what we are being told. Infamous hoaxes such as The Painted Bird, Misha and the Oprah-endorsed Angel at the Fence have done tremendous harm to the credibility of the Holocaust memoir as a genre. Gordon turns Opdyke's genuinely inspirational and dramatic story into a compendium of phony, fictionally "dramatic" scenes. Even those who have not read Opdyke's memoirs may leave feeling doubtful about the veracity of her story as presented here. And doubt is a dangerous reaction to a Holocaust story.

I liked Irena's Vow rather more than Adam did, but I can't disagree with his basic point. I think, as he does, that film and theatre works that sell themselves as being based on fact owe a certain deference to what really transpired, and that exaggeration for entertainment purposes risks damaging the message that the work was originally created to support. Where Adam and I differ, however, is the amount of damage Gordon's changes cause.

First, the books Adam cites were originally presented as factual retellings of events the authors themselves had lived through. Someone distorting his or her experiences and passing them off as fact is, in my view, not equivalent to a playwright adapting a memoir for the theatre and introducing events or characters that support the stage work. It is not possible in any real way for anyone to mistake Irena's Vow for In My Hands: Memories of a Holocaust Rescuer. Just about any audience member who purchases a ticket will be well aware that they are not seeing strict documentary theatre akin to The Laramie Project.

Second, while I do concede to Adam and other critics (such as Charles Isherwood in The New York Times) that there is something of an artificiality to many situations in the play, that did not, for me, detract from the overall message or effect of the piece as a production. To my eye, Irena's Vow employed its changes to celebrate Opdyke and all the unsung heroes who risked their lives to fight the evils of the Holocaust, and that telling that story was important enough to risk critiques such as Adam's. And because—whatever else he may have done—Gordon did not violate Opdyke's work or dignity, his alterations ultimately contribute to a greater truth.

That doesn't excuse Gordon's changes, but it's the nature of the theatrical beast. Even if the baby wasn't actually born during the time Irena was hiding the Jews, it helps amplify the pressure and the danger she and her 13 charges were in. The most realistic play would likely find Tovah Feldshuh constantly running between the major and the Jews, trying to keep him away from the cellar and shushing them so they won't be discovered. But that's almost certainly not a play anyone would have any interest in seeing, and regardless of how factually accurate it may be, it's not necessarily more true.

The distinction between fact and truth in the film and theatre is a difficult one, and everyone has their own tolerance level for how one is treated with respect to the other. I found Irena's Vow within the realm of acceptability, Adam did not, and you might have a different viewpoint still. Regardless of where he, I, or you stand, this strikes me as a conversation well worth having.

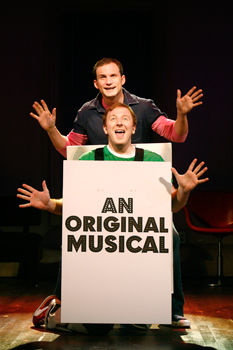

It occurred to me after reading Adam's piece that I had a similar reaction to another show that opened on Broadway this season, albeit one as dissimilar as imaginable to Irena's Vow: [title of show]. With it, I was as unwilling and/or unable as Adam was with Gordon's play to make the leaps the writers required of me. Ultimately, that one bothered me more. I won't pretend that its subject, about the writing and production of a new musical, carries any of the potential weight, meaning, or significance of the story Gordon treats. But it was precisely because it had nothing vital to say that its prevarications struck me as so damaging.

It occurred to me after reading Adam's piece that I had a similar reaction to another show that opened on Broadway this season, albeit one as dissimilar as imaginable to Irena's Vow: [title of show]. With it, I was as unwilling and/or unable as Adam was with Gordon's play to make the leaps the writers required of me. Ultimately, that one bothered me more. I won't pretend that its subject, about the writing and production of a new musical, carries any of the potential weight, meaning, or significance of the story Gordon treats. But it was precisely because it had nothing vital to say that its prevarications struck me as so damaging.

I saw [title of show] at the inaugural New York Musical Theatre in 2004, I reviewed it at the Vineyard Theatre in 2006, and then I reviewed it again on Broadway earlier this season. At each juncture, writers Jeff Bowen and Hunter Bell passed off the story as true (their characters in the show used their own names), even though it became progressively more fictional with each incarnation. While I've never loved the show, I do think the NYMF production benefited from its verisimilitude: Bell and Bowen were so committed to getting the tiniest details about theatrical minutiae (and the Festival) right that they placed the show firmly within the real world, so when a major plot point involved Heidi Blickenstaff's character fretting about being replaced by Emily Skinner for the NYMF run, you believed it.

But in the production at the Vineyard, Heidi fought with Jeff and Hunter and faced the Skinner replacement after NYMF; on Broadway, Heidi's problems cropped up following the Vineyard run and was this time to be spelled by... Sutton Foster. That references to the theatre that once gave the show gravitas were now peppered with anachronisms proved even more that Bell and Bowen were interested in something else than telling their story. (Bell said in a Playbill interview that events in the show "came out of seeds of stress," which while perhaps technically correct is nonetheless misleading.) That didn't matter to the show's most ardent fans—nor should it, necessarily—but it did to me: I felt Bowen and Bell were sabotaging the show by selling it on their innocence and dedication to the craft, yet peddling sweeping and provable inaccuracies and distortions while claiming in the "inspirational" finale number, "Nine People's Favorite Thing," that they would never stoop so low.

So, yes, I find this a worse transgression than Gordon's with Irena's Vow, because Bell and Bowen were willfully misrepresenting their own story with no more significant message to get across. As potentially troubling as Gordon's embellishments of Opdyke's story are, they do serve the purpose of introducing us to a remarkable woman who faced incredible sacrifices to save others and for reminding us that supreme beauty can exist even within utter ugliness. Bell and Bowen can claim no goal so lofty—and went at least as far as Gordon did, even about a subject that will never impact the world the way Opdyke's daring did.

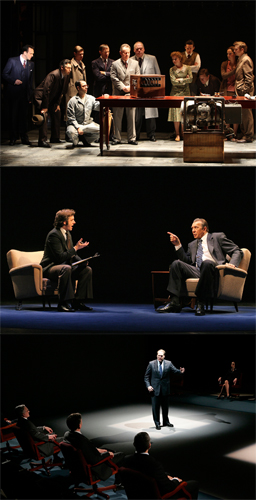

As the theatre tries to sate its increasing hunger for ideas by turning to actual events, this is a trend we can only expect to see more and more. In fact, it's already been prevalent in recent years—with outcomes not appreciably different than Irena's Vow and [title of show]. Aaron Sorkin's play The Farnsworth Invention, told the story of the creation and establishment of television, and had its climax in the courtroom where Philo Farnsworth was denied "priority of invention" for the television—when, in truth, he was awarded it. Peter Morgan's Frost/Nixon, seen on Broadway in 2007 and recently made into a Hollywood film, invented a crucial scene between David Frost and Richard Nixon and made significant changes to history for the purposes of the drama. In Stuff Happens, which played at The Public Theater in 2006, David Hare placed George W. Bush, Condoleezza Rice, and others in a historical drama that twisted certain facts to make its pungent comment on the American government before and during the Iraq War.

As the theatre tries to sate its increasing hunger for ideas by turning to actual events, this is a trend we can only expect to see more and more. In fact, it's already been prevalent in recent years—with outcomes not appreciably different than Irena's Vow and [title of show]. Aaron Sorkin's play The Farnsworth Invention, told the story of the creation and establishment of television, and had its climax in the courtroom where Philo Farnsworth was denied "priority of invention" for the television—when, in truth, he was awarded it. Peter Morgan's Frost/Nixon, seen on Broadway in 2007 and recently made into a Hollywood film, invented a crucial scene between David Frost and Richard Nixon and made significant changes to history for the purposes of the drama. In Stuff Happens, which played at The Public Theater in 2006, David Hare placed George W. Bush, Condoleezza Rice, and others in a historical drama that twisted certain facts to make its pungent comment on the American government before and during the Iraq War.

Many theatregoers were entertained or invigorated by these plays, as others were by Irena's Vow and [title of show]. But if they thought they were being informed—and in all five cases that is obviously what the creators, on some level, wanted them to think—they were wrong. Whether they wrote off what they saw as merely "a night at the theatre," dug in to research these topics and learn the truth about them, or (what I believe Adam fears most) accepted as truth what they saw and now live based on that belief, is impossible to know. But I think it's fair to say that probably a little bit of each happened with all the shows—resulting in some people who know more, some people who know less, and others who took away nothing. I'm not sure which of the latter two is worse.

Is saying anything, be it about creating a musical or inventing television or criticizing politics or paying tribute to the heroes of the Holocaust, worth that? Is it ever right for a theatre piece to be intentionally wrong—even if it is for the right reasons? I'd love to hear your thoughts on this.

Photos (top to bottom): Tovah Feldshuh in Irena's Vow (photo by Carol Rosegg); Jeff Bowen and Hunter Bell in [title of show] (photo by Carol Rosegg); the cast ofThe Farnsworth Invention (photo by Joan Marcus); Michael Sheen and Frank Langella inFrost/Nixon (photo by Joan Marcus); Jay O. Sanders (right) and the cast of Stuff Happens (photo by Michal Daniel).

Sunday, April 05, 2009 at 11:54 AM | Item Link

The last five columns written by Matthew Murray:

04/11/2009: They Don't Write the Music, but They Make it Sound Great

04/05/2009: Tell Me It's Not True

03/13/2009: Once in a Long Weill

03/07/2009: The (Almost) Glamorous Life

03/05/2009: Only for... Uh... Well... Sometime...

For a listing of all features written by Matthew, click here.

[Advertisement]

[Advertisement]

If you would like to contact us, you can email us at feedback@

broadwaystars.com

[Advertisement]

[Advertisement]

- July 15: Harry Connick, Jr. in Concert on Broadway - Neil Simon

- Sept. 28: Brief Encounter - Studio 54

- Sept. 30: The Pitmen Painters - Samuel J. Friedman Theatre

- Oct. 3: Mrs. Warren's Profession - American Airlines Theatre

- Oct. 7: Time Stands Still - Cort Theatre

- Oct. 12: A Life In The Theatre - Schoenfeld Theatre

- Oct. 13: Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson - Bernard Jacobs Theatre

- Oct. 14: La Bete - The Music Box Theatre

- Oct. 21: Lombardi - Circle In The Square

- Oct. 25: Driving Miss Daisy - John Golden Theatre

- Oct. 26: Rain - A Tribute To The Beatles On Broadway - Neil Simon Theatre

- Oct. 31: The Scottsboro Boys - Lyceum Theatre

- Nov. 4: Women On The Verge Of A Nervous Breakdown - Belasco Theatre

- Nov. 9: Colin Quinn Long Story Short - Helen Hayes Theatre

- Nov. 11: The Pee-Wee Herman Show - Stephen Sondheim Theatre

- Nov. 13: The Merchant of Venice - The Broadhurst Theatre

- Nov. 14: Elf - Al Hirschfeld Theatre

- Nov. 18: A Free Man Of Color - Vivian Beaumont Theater

- Nov. 21: Elling - Ethel Barrymore Theatre

- Dec. 9: Donny & Marie: A Broadway Christmas - Marquis Theater

- Jan. 13: The Importance of Being Earnest - American Airlines Theatre

- Mar. 3: Good People - Samuel J. Friedman Theatre

- Mar. 6: That Championship Season - Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre

- Mar. 11: Kathy Griffin Wants a Tony - Belasco

- Mar. 17: Arcadia - Barrymore Theatre

- Mar. 20: Priscilla Queen Of The Desert The Musical - The Palace Theatre

- Mar. 22: Ghetto Klown - Lyceum Theatre

- Mar. 24: The Book Of Mormon - Eugene O'Neill Theatre

- Mar. 27: How To Succeed In Business Without Really Trying - Al Hirschfeld Theatre

- Mar. 31: Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo - Richard Rodgers Theatre

- Apr. 7: Anything Goes - Stephen Sondheim Theatre

- Apr. 10: Catch Me If You Can - The Neil Simon Theatre

- Apr. 11: The Motherf**ker with the Hat - Gerald Schoenfeld Theatre

- Apr. 14: War Horse - Vivian Beaumont Theater

- Apr. 17: Wonderland: A New Alice. A New Musical Adventure. - Marquis Theatre

- Apr. 19: High - Booth Theatre

- Apr. 20: Sister Act - The Broadway Theatre

- Apr. 21: Jerusalem - Music Box

- Apr. 24: Born Yesterday - Cort Theatre

- Apr. 25: The House of Blue Leaves - Walter Kerr Theatre

- Apr. 26: Fat Pig - Belasco Theatre

- Apr. 27: Baby It's You! - Broadhurst Theatre

- Apr. 27: The Normal Heart - Golden Theater

- Apr. 28: The People in the Picture - Studio 54

- Apr. 28: The End of The Season

- Jun. 12: The 65th Annual Tony Awards - Beacon Theatre

- June 14: Spider-Man, Turn Off The Dark - Foxwoods Theater

- June 21: Master Class - Samuel J. Friedman