[Advertisement]

[Advertisement]

TICKET / INFO

- StudentRush

- New York Show Tickets

- Givenik.com

- Telecharge.com

- Ticketmaster.com

- Group Sales Box Office

- Frugal TheaterGoer

- Broadway for Broke People

- Playbill's Rush/Lottery/SR

- Seating Charts

COMMUNITY

NEWS

- Back Stage

- Bloomberg

- Broadway.com

- BroadwayWorld

- Entertainment Weekly

- NYTheatre.com

- New York Magazine

- The New York Daily News

- The New York Post

- The New York Times

- The New Yorker

- Newsday

- NiteLife Exchange

- Playbill

- Show Business Weekly

- The Star-Ledger

- Talkin'Broadway

- TheaterMania.com

- Time Out New York

- American Theatre Magazine

- Theatre Development Fund (TDF)

- Best of Off-Broadway

- The Village Voice

- Variety

- The Wall Street Journal

- Journal News

REVIEWS

- The New York Times

- Variety

- New York Post

- NY1

- Aisle Say

- CurtainUp

- DC Theatre Scene

- Show Showdown

- Stage and Cinema

- StageGrade

- Talk Entertainment

- TotalTheater.com

- Off-Off Broadway Review

- TheaterOnline.com

- TheaterScene.net

- TheaterNewsOnline.com

WEST END

- The Stage

- 1st 4 London Theatre Tickets

- Book Your Theatre Tickets

- Compare Theatre Tickets.co.uk

- Theatre.com

- Whatsonstage.com [UK]

- ATW - London

- Musical Stages [UK]

- Albemarle of London

- Londontheatre.co.uk

- Google News

- Show Pairs

- ILoveTheatre.com

- The Official London Theatre Guide

- UK Tickets

BOSTON

CHICAGO

LA/SF

COLUMNS

- Peter Bart

- Andrew Cohen

- Ken Davenport

- Tim Dunleavy

- Peter Filichia

- Andrew Gans

- Ernio Hernandez

- Harry Haun

- Chad Jones

- Chris Jones

- James Marino

- Joel Markowitz

- Matthew Murray

- Michael Musto

- Ellis Nassour

- Tom Nondorf

- Richard Ouzounian

- Michael Portantiere

- Rex Reed

- Michael Riedel

- Frank Rizzo

- Richard Seff

- Frank Scheck

- Mark Shenton

- John Simon

- Robert Simonson

- Steve on Broadway (SOB)

- Steven Suskin

- Terry Teachout

- Theater Corps

- Elisabeth Vincentelli

- Hedy Weiss

- Matt Windman

- Linda Winer

- Matt Wolf

PODCAST

RADIO

TV

- Theater Talk

- BlueGobo.com

- Classic Arts Showcase

- American Theatre Wing Seminars

- Women in Theatre

- NY1

- WCBS [2]

- WNBC [4]

- FOX [5]

- WABC [7]

- WWOR [9]

- WPIX [11]

- Channel 13

- Hulu

- YouTube

AWARDS

- Tony Central

- Oscar Central

- Tony Awards

- Drama Desk Awards

- The Drama League Awards

- Lortel Awards

- Academy Awards

- Emmy Awards

- Grammy Awards

- GoldDerby

DATABASE

- Internet Broadway Database

- Internet Off-Broadway Database

- Internet Movie Database

- Internet Theatre Database

- Musical Cast Album Database

- [CastAlbums.org]

- Show Music on Record Database (LOC)

- CurtainUp Master Index of Reviews

- Musical Heaven

- StageSpecs.org

ROAD HOUSES

- Gammage [AZ]

- Golden Gate [CA]

- Curran [CA]

- Orpheum [CA]

- Community Center [CA]

- Civic [CA]

- Ahmanson [CA]

- Pantages [CA]

- Temple Hoyne Buell [CO]

- Palace [CT]

- Rich Forum [CT]

- Shubert [CT]

- Bushnell [CT]

- Chevrolet [CT]

- Broward Center [FL]

- Jackie Gleason [FL]

- Fox [GA]

- Civic Center [IA]

- Cadillac Palace [IL]

- Ford Center/Oriental [IL]

- The Bank of America Theatre [IL]

- Auditorium Theatre of Roosevelt University [IL]

- Kentucky Center [KY]

- France-Merrick [MD]

- Colonial [MA]

- Wilbur [MA]

- Charles [MA]

- Wang [MA]

- Wharton Center [MI]

- Whiting [MI]

- Fisher [MI]

- Masonic Temple [MI]

- Orpheum, State, and Pantages [MN]

- Fabulous Fox [MO]

- New Jersey PAC [NJ]

- Auditorium Center [NY]

- Proctors [NY]

- Shea's PAC [NY]

- BTI Center [NC]

- Blumenthal PAC [NC]

- Schuster PAC [OH]

- Playhouse Square [OH]

- Aronoff Center [OH]

- Ohio [OH]

- Victoria Theatre [OH]

- Birmingham Jefferson [OH]

- Merriam Theater [PA]

- Academy of Music [PA]

- Benedum Center [PA]

- Providence PAC [RI]

- Orpheum [TN]

- Hobby Center [TX]

- Music Hall [TX]

- Bass Hall [TX]

- Paramount [WA]

- Fox Cities PAC [WI]

- Marcus Center [WI]

- Weidner Center [WI]

FESTIVALS

- The New York International Fringe Festival

- The American Living Room Festival

- Summer Play Festival

- The New York Musical Theatre Festival

- Adirondack Theatre Festival

- NAMT: Festival of New Musicals

SPECIAL

- BC/EFA: Broadway Cares / Equity Fights AIDS

- The Actors' Fund

- Stage Directors and Choreographers Foundation

EDUCATION

- Google Shakespeare

- Actor Tips

- AACT

- ArtSearch

- Broadway Classroom

- Broadway Educational Alliance

- Camp Broadway

- Great Groups - New York Actors

- Theatre Communications Group (TCG)

- Theatre Development Fund (TDF)

- Off-Broadway Theater Information Center

UNIONS/TRADE

- AEA

- SAG

- AFTRA

- AGMA

- The League

- APAP

- Local 1

- ATPAM

- IATSE

- AFM

- AFM - Local 802

- Treasurers & Ticket Sellers Union

- DGA

- Dramatists Guild

- USA 829

- WGA, East

- WGA, West

- SSD&C

- AFL-CIO

- League of Professional Theatre Women

NYC NON-PROFITS

- Cherry Lane Theatre

- City Center

- Drama Dept.

- Ensemble Studio Theater

- Jean Cocteau Rep.

- Lark

- Lincoln Center Theater

- Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts

- Lucille Lortel Foundation

- Manhattan Theatre Club

- MCC

- Mint

- Pearl Theatre Company

- Public Theater

- Roundabout

- Second Stage

- Signature

- The Vineyard Theatre

- The York Theatre Company

REGIONAL

- Actors Theatre

- Alabama Shakespeare Festival

- Alley Theatre

- ACT

- American Musical Theatre in San Jose

- American Repertory

- Arena Stage

- Barrington Stage Company

- Bay Street Theatre

- Berkeley Rep

- Casa Manana

- Chicago Shakespeare Theater

- Cincinnati Playhouse

- CTC

- Dallas Summer Musicals

- Dallas Theater Center

- Denver Center

- George Street

- Goodman

- Guthrie

- Goodspeed

- Hartford Stage

- Hudson Stage Company

- Theatre de la Jeune Lune

- Kennedy Center

- La Jolla

- Long Wharf

- Lyric Stage

- Mark Taper Forum

- McCarter

- New Jersey Rep

- North Shore

- Old Globe

- Ordway

- Oregon Shakespeare

- Paper Mill

- Prince Music Theater

- The Rep (St. Louis)

- Sacramento Music Circus

- San Francisco Mime Troupe

- Seattle Rep

- Shakespeare Theatre Co. (DC)

- The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey

- South Coast Rep

- Steppenwolf

- Theater of the Stars (GA)

- Theater J (DC)

- Theater Under the Stars (TX)

- Trinity Rep

- Two River Theater Company

- Utah

- Victory Gardens

- Westport

- Williamstown

- Yale Rep

KEWL

[Advertisement]

One sure sign of a great artist: His failures are more noteworthy than most others' successes. Kurt Weill, for example, earned his station in musical theatre posterity because of hits, but his one big Broadway bomb, The Firebrand of Florence, contains his most richly romantic and instantly accessible music. Last night at Alice Tully Hall at Lincoln Center, The Collegiate Chorale gave that show its first public hearing in New York in nearly 64 years, under the direction of Roger Rees and the conducting baton of Ted Sperling. And they made a triumph of something that's long been considered a tragedy.

One sure sign of a great artist: His failures are more noteworthy than most others' successes. Kurt Weill, for example, earned his station in musical theatre posterity because of hits, but his one big Broadway bomb, The Firebrand of Florence, contains his most richly romantic and instantly accessible music. Last night at Alice Tully Hall at Lincoln Center, The Collegiate Chorale gave that show its first public hearing in New York in nearly 64 years, under the direction of Roger Rees and the conducting baton of Ted Sperling. And they made a triumph of something that's long been considered a tragedy.

Operetta had all but dissolved into the mists of Ruritania when The Firebrand of Florence opened (and closed) in the spring of 1945. There had been and would continue to be a few outliers (including the Sidney Romberg–Dorothy Fields–Herbert Fields Up in Central Park, which opened earlier that year and would run into 1946), but for most part the genre that had owned the 1920s was functionally moribund. Still, it remained potent in the memories of audiences and composers, so it makes sense that Weill, teaming up again with lyricist Ira Gershwin (their first show had been the smash Gertrude Lawrence vehicle Lady in the Dark), would want to try his hand. Edwin Justus Mayer's 1924 play The Firebrand, loosely based on the life of Renaissance Renaissance man Benvenuto Cellini, would seem to provide the requisite Italian color and swashbuckling sweep.

Things didn't quite work out. Despite an energetic story, in which Cellini wove in and out of Florence's public squares and bedchambers, dodged the spoonerism-spouting Duke and Duchess of Florence, and repeatedly getting arrested for this or that transgression, the operetta-ization quickly closed. Several reasons have been given for this over the years, and one suspects Rees and company agree most with the one that cites the lack of zest in Mayer's own adaptation of his play—Rees and company ignored the book as much as they could. But his light-handed semi-staging, blended with Sperling's decisive conducting of the forcefully beautiful score, made The Firebrand of Florence seem like it should have always been a hit.

At least in terms of its music. Combining a trio of elaborately structured musical scenes (Cellini's trial in the court of public opinion, a farcical Act I finale, and a Gilbert-and-Sullivan-style courtroom spectacle in Act II) with soaring songs of every sort, this is a show that is borne aloft time and time again by tidal waves of incomparable compositions. The "Come to Flornece" chorus and Cellini's establishing "Life, Love, and Laughter" are as musically addicting and adventurous as any better-known songs from Broadway's more successful shows of the period, and so emotionally vibrant that they practically defy comparison with most Broadway songs written in the last 30 years or so. Gershwin's lyrics don't shy away from filigree, but don't devote themselves to it either—the effect of his words against Weill's tunes is of hearing a thoroughly modern (for the day) operetta that just happens to be set in 17th-century Italy.

This is hardly accidental: Weill was the ultimate musical chameleon, capable of writing any type of show in any form without traversing the same road twice, and he elicited vivacious versatility from all of his collaborators as well. You get a sense in this show of Lady in the Dark's urgent fluidity or One Touch of Venus's carefree bounce, but this score sounds and behaves nothing like those— or any other title in its ostensible genre. Here, Weill and Gershwin were blending operetta with popular Broadway, so their score reflects as much the sensibilities of the soon-to-appear Brigadoon and Finian's Rainbow as it does the established and geriatric ones of Kern and Romberg. (Carousel, however, also from 1945, remains in a class of its own.)

So convincing did The Collegiate Chorale make the show as a composition, it's hard to believe the original production could have flopped after only 43 performances. Perhaps the deciding factor really was Mayer's libretto, or even the cast led by the estimable Lotte Lenya (who, it's true, is hard to imagine as the come-hither Duchess). But with opera star Nathan Gunn an effortlessly magnetic (and flawlessly sung) Cellini, Anna Christy as his golden-voiced model-muse Angela, Broadway stalwarts Terrence Mann and Victoria Clark as the Duke and Duchess, and key supporting roles filled by the full-bodied ham David Pittu and the lusty mezzo Krysty Swann, such problems were not replicated last night. Nothing stood in the way of music, which made it seem that nothing could.

Only Rees failed to satisfy, the often-rhyming narration he read to smooth over the excision of dozens of dialogue pages hurting the flow of the entertainment more than helping it. But his direction was sure and usually very funny, and he made the most of what could have been two-dimensional staging and one-dimensional drama thanks to all the missing (or frayed) narrative threads. Simply given the nature of the evening, the unquestionable king of the concert was Sperling, whose mastery of the New York City Opera Orchestra was top-notch and who didn't miss a nuance of the score's up-to-the-minute old-fashionedness. But Rees's theatrical common sense was a crucial glue.

Only Rees failed to satisfy, the often-rhyming narration he read to smooth over the excision of dozens of dialogue pages hurting the flow of the entertainment more than helping it. But his direction was sure and usually very funny, and he made the most of what could have been two-dimensional staging and one-dimensional drama thanks to all the missing (or frayed) narrative threads. Simply given the nature of the evening, the unquestionable king of the concert was Sperling, whose mastery of the New York City Opera Orchestra was top-notch and who didn't miss a nuance of the score's up-to-the-minute old-fashionedness. But Rees's theatrical common sense was a crucial glue.

At least for a single concert. The Firebrand of Florence being revived today on any scale is unthinkable; if another chance comes around even within the next 64 years, it will be one of those miracles that only the theatre seems able to produce. But for those smart enough to trudge up to Lincoln Center last night, this one-night-only event was more than enough to sate the appetite. There are always other things to gorge on, true, but certain recipes are necessarily of the moment; The Collegiate Chorale knew just what it was doing. If the group is already planning its next feast, and it's still interested in underappreciated Weill, may I recommend serving a few courses of Love Life?

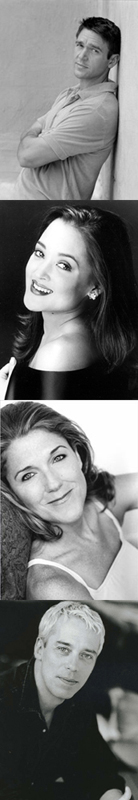

Photos (top to bottom): Nathan Gunn, Anna Christy, Victoria Clark, and Terrence Mann; the original cast of The Firebird of Florence (photo courtesy of the Ira and Leonore Gershwin Trusts)

Friday, March 13, 2009 at 12:01 AM | Item Link

The last five columns written by Matthew Murray:

04/11/2009: They Don't Write the Music, but They Make it Sound Great

04/05/2009: Tell Me It's Not True

03/13/2009: Once in a Long Weill

03/07/2009: The (Almost) Glamorous Life

03/05/2009: Only for... Uh... Well... Sometime...

For a listing of all features written by Matthew, click here.

[Advertisement]

[Advertisement]

If you would like to contact us, you can email us at feedback@

broadwaystars.com

[Advertisement]

[Advertisement]

- July 15: Harry Connick, Jr. in Concert on Broadway - Neil Simon

- Sept. 28: Brief Encounter - Studio 54

- Sept. 30: The Pitmen Painters - Samuel J. Friedman Theatre

- Oct. 3: Mrs. Warren's Profession - American Airlines Theatre

- Oct. 7: Time Stands Still - Cort Theatre

- Oct. 12: A Life In The Theatre - Schoenfeld Theatre

- Oct. 13: Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson - Bernard Jacobs Theatre

- Oct. 14: La Bete - The Music Box Theatre

- Oct. 21: Lombardi - Circle In The Square

- Oct. 25: Driving Miss Daisy - John Golden Theatre

- Oct. 26: Rain - A Tribute To The Beatles On Broadway - Neil Simon Theatre

- Oct. 31: The Scottsboro Boys - Lyceum Theatre

- Nov. 4: Women On The Verge Of A Nervous Breakdown - Belasco Theatre

- Nov. 9: Colin Quinn Long Story Short - Helen Hayes Theatre

- Nov. 11: The Pee-Wee Herman Show - Stephen Sondheim Theatre

- Nov. 13: The Merchant of Venice - The Broadhurst Theatre

- Nov. 14: Elf - Al Hirschfeld Theatre

- Nov. 18: A Free Man Of Color - Vivian Beaumont Theater

- Nov. 21: Elling - Ethel Barrymore Theatre

- Dec. 9: Donny & Marie: A Broadway Christmas - Marquis Theater

- Jan. 13: The Importance of Being Earnest - American Airlines Theatre

- Mar. 3: Good People - Samuel J. Friedman Theatre

- Mar. 6: That Championship Season - Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre

- Mar. 11: Kathy Griffin Wants a Tony - Belasco

- Mar. 17: Arcadia - Barrymore Theatre

- Mar. 20: Priscilla Queen Of The Desert The Musical - The Palace Theatre

- Mar. 22: Ghetto Klown - Lyceum Theatre

- Mar. 24: The Book Of Mormon - Eugene O'Neill Theatre

- Mar. 27: How To Succeed In Business Without Really Trying - Al Hirschfeld Theatre

- Mar. 31: Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo - Richard Rodgers Theatre

- Apr. 7: Anything Goes - Stephen Sondheim Theatre

- Apr. 10: Catch Me If You Can - The Neil Simon Theatre

- Apr. 11: The Motherf**ker with the Hat - Gerald Schoenfeld Theatre

- Apr. 14: War Horse - Vivian Beaumont Theater

- Apr. 17: Wonderland: A New Alice. A New Musical Adventure. - Marquis Theatre

- Apr. 19: High - Booth Theatre

- Apr. 20: Sister Act - The Broadway Theatre

- Apr. 21: Jerusalem - Music Box

- Apr. 24: Born Yesterday - Cort Theatre

- Apr. 25: The House of Blue Leaves - Walter Kerr Theatre

- Apr. 26: Fat Pig - Belasco Theatre

- Apr. 27: Baby It's You! - Broadhurst Theatre

- Apr. 27: The Normal Heart - Golden Theater

- Apr. 28: The People in the Picture - Studio 54

- Apr. 28: The End of The Season

- Jun. 12: The 65th Annual Tony Awards - Beacon Theatre

- June 14: Spider-Man, Turn Off The Dark - Foxwoods Theater

- June 21: Master Class - Samuel J. Friedman