[Broadway Ad Network]

[Broadway Ad Network]

TICKET / INFO

- StudentRush

- New York Show Tickets

- Givenik.com

- Telecharge.com

- Ticketmaster.com

- Group Sales Box Office

- Frugal TheaterGoer

- Broadway for Broke People

- Playbill's Rush/Lottery/SR

- Seating Charts

COMMUNITY

NEWS

- Back Stage

- Bloomberg

- Broadway.com

- BroadwayWorld

- Entertainment Weekly

- NYTheatre.com

- New York Magazine

- The New York Daily News

- The New York Post

- The New York Times

- The New Yorker

- Newsday

- NiteLife Exchange

- Playbill

- Show Business Weekly

- The Star-Ledger

- Talkin'Broadway

- TheaterMania.com

- Time Out New York

- American Theatre Magazine

- Theatre Development Fund (TDF)

- Best of Off-Broadway

- The Village Voice

- Variety

- The Wall Street Journal

- Journal News

REVIEWS

- The New York Times

- Variety

- New York Post

- NY1

- Aisle Say

- CurtainUp

- DC Theatre Scene

- Show Showdown

- Stage and Cinema

- StageGrade

- Talk Entertainment

- TotalTheater.com

- Off-Off Broadway Review

- TheaterOnline.com

- TheaterScene.net

- TheaterNewsOnline.com

WEST END

- The Stage

- 1st 4 London Theatre Tickets

- Book Your Theatre Tickets

- Compare Theatre Tickets.co.uk

- Theatre.com

- Whatsonstage.com [UK]

- ATW - London

- Musical Stages [UK]

- Albemarle of London

- Londontheatre.co.uk

- Google News

- Show Pairs

- ILoveTheatre.com

- The Official London Theatre Guide

- UK Tickets

BOSTON

CHICAGO

LA/SF

COLUMNS

- Peter Bart

- Andrew Cohen

- Ken Davenport

- Tim Dunleavy

- Peter Filichia

- Andrew Gans

- Ernio Hernandez

- Harry Haun

- Chad Jones

- Chris Jones

- James Marino

- Joel Markowitz

- Matthew Murray

- Michael Musto

- Ellis Nassour

- Tom Nondorf

- Richard Ouzounian

- Michael Portantiere

- Rex Reed

- Michael Riedel

- Frank Rizzo

- Richard Seff

- Frank Scheck

- Mark Shenton

- John Simon

- Robert Simonson

- Steve on Broadway (SOB)

- Steven Suskin

- Terry Teachout

- Theater Corps

- Elisabeth Vincentelli

- Hedy Weiss

- Matt Windman

- Linda Winer

- Matt Wolf

PODCAST

RADIO

TV

- Theater Talk

- BlueGobo.com

- Classic Arts Showcase

- American Theatre Wing Seminars

- Women in Theatre

- NY1

- WCBS [2]

- WNBC [4]

- FOX [5]

- WABC [7]

- WWOR [9]

- WPIX [11]

- Channel 13

- Hulu

- YouTube

AWARDS

- Tony Central

- Oscar Central

- Tony Awards

- Drama Desk Awards

- The Drama League Awards

- Lortel Awards

- Academy Awards

- Emmy Awards

- Grammy Awards

- GoldDerby

DATABASE

- Internet Broadway Database

- Internet Off-Broadway Database

- Internet Movie Database

- Internet Theatre Database

- Musical Cast Album Database

- [CastAlbums.org]

- Show Music on Record Database (LOC)

- CurtainUp Master Index of Reviews

- Musical Heaven

- StageSpecs.org

ROAD HOUSES

- Gammage [AZ]

- Golden Gate [CA]

- Curran [CA]

- Orpheum [CA]

- Community Center [CA]

- Civic [CA]

- Ahmanson [CA]

- Pantages [CA]

- Temple Hoyne Buell [CO]

- Palace [CT]

- Rich Forum [CT]

- Shubert [CT]

- Bushnell [CT]

- Chevrolet [CT]

- Broward Center [FL]

- Jackie Gleason [FL]

- Fox [GA]

- Civic Center [IA]

- Cadillac Palace [IL]

- Ford Center/Oriental [IL]

- The Bank of America Theatre [IL]

- Auditorium Theatre of Roosevelt University [IL]

- Kentucky Center [KY]

- France-Merrick [MD]

- Colonial [MA]

- Wilbur [MA]

- Charles [MA]

- Wang [MA]

- Wharton Center [MI]

- Whiting [MI]

- Fisher [MI]

- Masonic Temple [MI]

- Orpheum, State, and Pantages [MN]

- Fabulous Fox [MO]

- New Jersey PAC [NJ]

- Auditorium Center [NY]

- Proctors [NY]

- Shea's PAC [NY]

- BTI Center [NC]

- Blumenthal PAC [NC]

- Schuster PAC [OH]

- Playhouse Square [OH]

- Aronoff Center [OH]

- Ohio [OH]

- Victoria Theatre [OH]

- Birmingham Jefferson [OH]

- Merriam Theater [PA]

- Academy of Music [PA]

- Benedum Center [PA]

- Providence PAC [RI]

- Orpheum [TN]

- Hobby Center [TX]

- Music Hall [TX]

- Bass Hall [TX]

- Paramount [WA]

- Fox Cities PAC [WI]

- Marcus Center [WI]

- Weidner Center [WI]

FESTIVALS

- The New York International Fringe Festival

- The American Living Room Festival

- Summer Play Festival

- The New York Musical Theatre Festival

- Adirondack Theatre Festival

- NAMT: Festival of New Musicals

SPECIAL

- BC/EFA: Broadway Cares / Equity Fights AIDS

- The Actors' Fund

- Stage Directors and Choreographers Foundation

EDUCATION

- Google Shakespeare

- Actor Tips

- AACT

- ArtSearch

- Broadway Classroom

- Broadway Educational Alliance

- Camp Broadway

- Great Groups - New York Actors

- Theatre Communications Group (TCG)

- Theatre Development Fund (TDF)

- Off-Broadway Theater Information Center

UNIONS/TRADE

- AEA

- SAG

- AFTRA

- AGMA

- The League

- APAP

- Local 1

- ATPAM

- IATSE

- AFM

- AFM - Local 802

- Treasurers & Ticket Sellers Union

- DGA

- Dramatists Guild

- USA 829

- WGA, East

- WGA, West

- SSD&C

- AFL-CIO

- League of Professional Theatre Women

NYC NON-PROFITS

- Cherry Lane Theatre

- City Center

- Drama Dept.

- Ensemble Studio Theater

- Jean Cocteau Rep.

- Lark

- Lincoln Center Theater

- Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts

- Lucille Lortel Foundation

- Manhattan Theatre Club

- MCC

- Mint

- Pearl Theatre Company

- Public Theater

- Roundabout

- Second Stage

- Signature

- The Vineyard Theatre

- The York Theatre Company

REGIONAL

- Actors Theatre

- Alabama Shakespeare Festival

- Alley Theatre

- ACT

- American Musical Theatre in San Jose

- American Repertory

- Arena Stage

- Barrington Stage Company

- Bay Street Theatre

- Berkeley Rep

- Casa Manana

- Chicago Shakespeare Theater

- Cincinnati Playhouse

- CTC

- Dallas Summer Musicals

- Dallas Theater Center

- Denver Center

- George Street

- Goodman

- Guthrie

- Goodspeed

- Hartford Stage

- Hudson Stage Company

- Theatre de la Jeune Lune

- Kennedy Center

- La Jolla

- Long Wharf

- Lyric Stage

- Mark Taper Forum

- McCarter

- New Jersey Rep

- North Shore

- Old Globe

- Ordway

- Oregon Shakespeare

- Paper Mill

- Prince Music Theater

- The Rep (St. Louis)

- Sacramento Music Circus

- San Francisco Mime Troupe

- Seattle Rep

- Shakespeare Theatre Co. (DC)

- The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey

- South Coast Rep

- Steppenwolf

- Theater of the Stars (GA)

- Theater J (DC)

- Theater Under the Stars (TX)

- Trinity Rep

- Two River Theater Company

- Utah

- Victory Gardens

- Westport

- Williamstown

- Yale Rep

KEWL

Theatre History 101 by Matthew Murray

-

It's become downright fashionable to blame audiences for the failure of any serious show these days—after all, haven't people become so stupid and sheeplike that if things aren't force-fed to them, they're not interested at all? Personally, I don't instantly buy into this candy-coated nugget of conventional wisdom, at least to the degree Charles Isherwood does in his New York Times piece today, "Theatrical Stumbles of Historic Proportions."

It's become downright fashionable to blame audiences for the failure of any serious show these days—after all, haven't people become so stupid and sheeplike that if things aren't force-fed to them, they're not interested at all? Personally, I don't instantly buy into this candy-coated nugget of conventional wisdom, at least to the degree Charles Isherwood does in his New York Times piece today, "Theatrical Stumbles of Historic Proportions."In it, Isherwood examines three shows this season that have had difficulties finding popular favor—Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson and The Scottsboro Boys, which will end their open-ended runs presently; and Lincoln Center's A Free Man of Color, which will not extend past its originally slated closing date— and concludes that audiences simply can't deal with high-minded, worldly subjects drawn from the pages of America's past. But I think the problem runs deeper than Isherwood is willing to look. The shows may be in-depth presentations of heavy topics, but they're so insistent about their ideological views that one must ask whether audiences are staying away not because they don't want to think, but because they do want to and aren't being given the chance.

I'd give Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson the edge here, if only for its daring: Portraying the seventh president of the United States as an emo pop star is unquestionably a bold choice. But by the final scenes, the color and irreverent humor that make the early show so jolting almost entirely vanish, leaving little more than a black-and-white morality play about America's historical treatment of Native Americans. While most of the musical involves Jackson battling historical expectations and fighting against his own worst inner self, his actions (and their outcome) in the last moments are carefully written and staged to program the audience with a certain point of view—and not exactly a happy one. Had writers Alex Timbers and Michael Friedman maintained until the very end their dual-edged portrait of Jackson as both an ambitious social reformer and an American proto-Hitler, they may have left mainstream audiences dazed, confused, and exhilarated. By choosing to end their show with a tableau of the Trail of Tears, Timbers and Friedman are tacitly admitting that open interpretation of a questionable life isn't really their goal after all.

The Scottsboro Boys has been justly acclaimed for its superb Kander and Ebb score, but David Thompson's book lacks its punch, originality, and dramatic vitality. Its problems are many—I've outlined some of them before—but perhaps none is more debilitating than in insisting on the audience's outrage about not just the Scottsboro boys' tragedy itself, but also the minstrel show genre of entertainment. The post-imprisonment fates of the black men falsely accused of rape were flattened out, perhaps for dramatic expediency but with the side-effect of painting them all as garden-variety victims until the last moments of their lives, even when fate and other circumstances made their lives far richer than what was depicted onstage. The framing device of a minstrel show, which climaxed in many of the black actors adorned in blackface plowing their way through a happy-go-lucky cakewalk against their characters' crumbling lives, and then literally and figuratively wiping it all away to expose as the façade, helped reassure the audience it was better than what it was seeing—not complicit in its very creation, as the earlier Cabaret and Chicago had. A friend of mine said that the show would be much more powerful (and historically accurate with regards to popular minstrelsy) had the black men played by white actors in blackface. That's a notion that's far more audacious and challenging an idea than anything in The Scottsboro Boys now, so much so that I'd shocked if it had even been considered, despite its obvious brilliance. But I'd also add that if the minstrel show is a deal-breaker, then the entire thing ought to be done as a real minstrel show, with an unbroken string of honest-intentioned tropes that lets the audience see for itself what society once accepted so willingly. In making the minstrel show palatable to modern sensibilities, Kander, Ebb, and Thompson all but eliminated its ability to have the devastating impact they wanted.

John Guare didn't torpedo his A Free Man of Color through the use of its show-within-a-show frame (though it rarely helped), but instead by insisting that countless resources support a message that ultimately amounted to little more than "The United States has always been a racist country." In presenting the free-wheeling New Orleans in the early 19th century as a shining beacon of enlightened thought, and the sea-to-shining-sea America in the wake of the Louisiana Purchase as one in which fear and hatred reigned, Guare stripped away the far more interesting racial nuances that characterize his earliest scenes. (Much is made—and then quickly dropped—of the fact that over a hundred terms existed at the time for every possible combination of skin color deriving from parents and ancestors of mixed-race origins.) By the end, his central character, Jacques Cornet, a full Mulatto (pure white father, pure black mother), who had always narrated the action, was reduced to telling the audience in no uncertain terms why they should lament the culture that allowed his disintegration. In fairness, the play was apparently originally intended as a five-and-a-half-hour epic, and has been reconfigured to just over two and a half for the Lincoln Center run, so perhaps a lot of intricacies were lost along the way. But the fact remains that a huge cast, expansive sets, and elaborate costumes are employed by one of the nation's premier nonprofits for the purpose of pointing out what Guare sees as America's nascent institutional racism. How many people likely to see A Free Man of Color go into it thinking prejudice is a worthwhile thing?

Isherwood scoffs at works like Inherit the Wind, The Coast of Utopia, Frost/Nixon, and The Farnsworth Invention for "presenting history as a comfortable stroll through a sepia-tinted, safely processed past." But what he neglects to mention is that those plays treated themselves as plays first—and that's a crucial part of why their fates were all at least somewhat rosier than those of this current trio. They focused on characters, stories, and conflict, leaving their historical background as background and their politics more as something each viewer had to supply on his or her own. Yes, Frost/Nixon and The Farnsworth Invention played loose with the truth, but they realized that entertainment was the vehicle for their messages and thus were far better as entertainment—and something that theatregoers were more willing to take a chance on.

The world is full of unsigned editorials, Bill O'Reillys, Frank Riches, and politicians who will be happy to tell you how to react to any topic or event; your boss and family will similarly demand that you operate on their terms. That's called life. Attending the theatre doesn't need to be a continuation of that, where your betters will instruct you in the only proper way to view any situation. Theatre can be more and better than that. It can be like The Coast of Utopia, where you're steeped in European history even as you're enraptured by the chronicle of a six-way friendship spanning decades several tumultuous decades. It can be like Inherit the Wind, which plays with actual events but boils down to a story about people and what drives them to do and believe the things they do. It can be like Doubt, where John Patrick Shanley presents the headline-friendly subject of child molestation in the Catholic church, but lets you decide for yourself whether you side with the accuser or the accused. It can even be like Cabaret or Chicago, which may be highly stylized, but nonetheless demand recognition of previous eras we'd prefer to forget—and the absorption of their hard lessons.

If a play's highest ambition is to be a lecture about a comfortable subject, it's going to have trouble finding people willing to sit and take it—whether it's about an historical event or not. (Last season's fictional Next Fall, a screeching screed about the evils of religion in a world becoming more accepting of homosexuality, eked out only 132 performances.) Maybe audiences do like their history processed and packaged. But that's what art is supposed to be: a re-envisioning of the world that tells us more than the real world could ever tell us about itself. Art that alludes and suggests, and doesn't just intone or yell, is more real and more attractive because it digs deeper. In your everyday life, don't you prefer to be engaged in discussions rather than scolded from a podium or patted on the back and then ignored? Why should theatre audiences be any different?

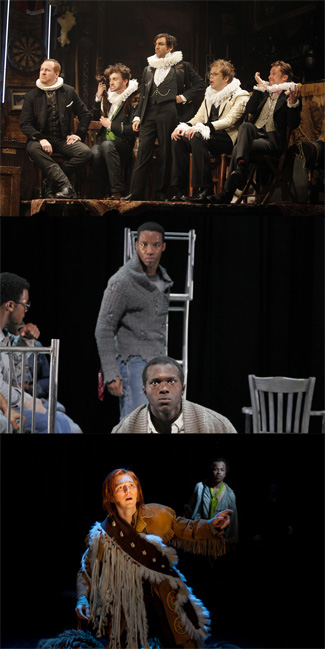

Photos: The cast of Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson, by Joan Marcus; Rodney Hicks and Joshua Henry in The Scottsboro Boys, by Paul Kolnik; and Paul Dano and Jeffrey Wright in A Free Man of Color, by T. Charles Erickson.

Why are you looking all the way down here?

For more articles by Matthew Murray, click the links below!

Previous: Make Friends with the Truth

Next: The Line of the Year 2010

Or go to the Archives

[Broadway Ad Network]

[Broadway Ad Network]

If you would like to contact us, you can email us at feedback@

broadwaystars.com

[Broadway Ad Network]

[Broadway Ad Network]

- July 15: Harry Connick, Jr. in Concert on Broadway - Neil Simon

- Sept. 28: Brief Encounter - Studio 54

- Sept. 30: The Pitmen Painters - Samuel J. Friedman Theatre

- Oct. 3: Mrs. Warren's Profession - American Airlines Theatre

- Oct. 7: Time Stands Still - Cort Theatre

- Oct. 12: A Life In The Theatre - Schoenfeld Theatre

- Oct. 13: Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson - Bernard Jacobs Theatre

- Oct. 14: La Bete - The Music Box Theatre

- Oct. 21: Lombardi - Circle In The Square

- Oct. 25: Driving Miss Daisy - John Golden Theatre

- Oct. 26: Rain - A Tribute To The Beatles On Broadway - Neil Simon Theatre

- Oct. 31: The Scottsboro Boys - Lyceum Theatre

- Nov. 4: Women On The Verge Of A Nervous Breakdown - Belasco Theatre

- Nov. 9: Colin Quinn Long Story Short - Helen Hayes Theatre

- Nov. 11: The Pee-Wee Herman Show - Stephen Sondheim Theatre

- Nov. 13: The Merchant of Venice - The Broadhurst Theatre

- Nov. 14: Elf - Al Hirschfeld Theatre

- Nov. 18: A Free Man Of Color - Vivian Beaumont Theater

- Nov. 21: Elling - Ethel Barrymore Theatre

- Dec. 9: Donny & Marie: A Broadway Christmas - Marquis Theater

- Jan. 13: The Importance of Being Earnest - American Airlines Theatre

- Mar. 3: Good People - Samuel J. Friedman Theatre

- Mar. 6: That Championship Season - Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre

- Mar. 11: Kathy Griffin Wants a Tony - Belasco

- Mar. 17: Arcadia - Barrymore Theatre

- Mar. 20: Priscilla Queen Of The Desert The Musical - The Palace Theatre

- Mar. 22: Ghetto Klown - Lyceum Theatre

- Mar. 24: The Book Of Mormon - Eugene O'Neill Theatre

- Mar. 27: How To Succeed In Business Without Really Trying - Al Hirschfeld Theatre

- Mar. 31: Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo - Richard Rodgers Theatre

- Apr. 7: Anything Goes - Stephen Sondheim Theatre

- Apr. 10: Catch Me If You Can - The Neil Simon Theatre

- Apr. 11: The Motherf**ker with the Hat - Gerald Schoenfeld Theatre

- Apr. 14: War Horse - Vivian Beaumont Theater

- Apr. 17: Wonderland: A New Alice. A New Musical Adventure. - Marquis Theatre

- Apr. 19: High - Booth Theatre

- Apr. 20: Sister Act - The Broadway Theatre

- Apr. 21: Jerusalem - Music Box

- Apr. 24: Born Yesterday - Cort Theatre

- Apr. 25: The House of Blue Leaves - Walter Kerr Theatre

- Apr. 26: Fat Pig - Belasco Theatre

- Apr. 27: Baby It's You! - Broadhurst Theatre

- Apr. 27: The Normal Heart - Golden Theater

- Apr. 28: The People in the Picture - Studio 54

- Apr. 28: The End of The Season

- Jun. 12: The 65th Annual Tony Awards - Beacon Theatre

- June 14: Spider-Man, Turn Off The Dark - Foxwoods Theater

- June 21: Master Class - Samuel J. Friedman