[Broadway Ad Network]

[Broadway Ad Network]

TICKET / INFO

- StudentRush

- New York Show Tickets

- Givenik.com

- Telecharge.com

- Ticketmaster.com

- Group Sales Box Office

- Frugal TheaterGoer

- Broadway for Broke People

- Playbill's Rush/Lottery/SR

- Seating Charts

COMMUNITY

NEWS

- Back Stage

- Bloomberg

- Broadway.com

- BroadwayWorld

- Entertainment Weekly

- NYTheatre.com

- New York Magazine

- The New York Daily News

- The New York Post

- The New York Times

- The New Yorker

- Newsday

- NiteLife Exchange

- Playbill

- Show Business Weekly

- The Star-Ledger

- Talkin'Broadway

- TheaterMania.com

- Time Out New York

- American Theatre Magazine

- Theatre Development Fund (TDF)

- Best of Off-Broadway

- The Village Voice

- Variety

- The Wall Street Journal

- Journal News

REVIEWS

- The New York Times

- Variety

- New York Post

- NY1

- Aisle Say

- CurtainUp

- DC Theatre Scene

- Show Showdown

- Stage and Cinema

- StageGrade

- Talk Entertainment

- TotalTheater.com

- Off-Off Broadway Review

- TheaterOnline.com

- TheaterScene.net

- TheaterNewsOnline.com

WEST END

- The Stage

- 1st 4 London Theatre Tickets

- Book Your Theatre Tickets

- Compare Theatre Tickets.co.uk

- Theatre.com

- Whatsonstage.com [UK]

- ATW - London

- Musical Stages [UK]

- Albemarle of London

- Londontheatre.co.uk

- Google News

- Show Pairs

- ILoveTheatre.com

- The Official London Theatre Guide

- UK Tickets

BOSTON

CHICAGO

LA/SF

COLUMNS

- Peter Bart

- Andrew Cohen

- Ken Davenport

- Tim Dunleavy

- Peter Filichia

- Andrew Gans

- Ernio Hernandez

- Harry Haun

- Chad Jones

- Chris Jones

- James Marino

- Joel Markowitz

- Matthew Murray

- Michael Musto

- Ellis Nassour

- Tom Nondorf

- Richard Ouzounian

- Michael Portantiere

- Rex Reed

- Michael Riedel

- Frank Rizzo

- Richard Seff

- Frank Scheck

- Mark Shenton

- John Simon

- Robert Simonson

- Steve on Broadway (SOB)

- Steven Suskin

- Terry Teachout

- Theater Corps

- Elisabeth Vincentelli

- Hedy Weiss

- Matt Windman

- Linda Winer

- Matt Wolf

PODCAST

RADIO

TV

- Theater Talk

- BlueGobo.com

- Classic Arts Showcase

- American Theatre Wing Seminars

- Women in Theatre

- NY1

- WCBS [2]

- WNBC [4]

- FOX [5]

- WABC [7]

- WWOR [9]

- WPIX [11]

- Channel 13

- Hulu

- YouTube

AWARDS

- Tony Central

- Oscar Central

- Tony Awards

- Drama Desk Awards

- The Drama League Awards

- Lortel Awards

- Academy Awards

- Emmy Awards

- Grammy Awards

- GoldDerby

DATABASE

- Internet Broadway Database

- Internet Off-Broadway Database

- Internet Movie Database

- Internet Theatre Database

- Musical Cast Album Database

- [CastAlbums.org]

- Show Music on Record Database (LOC)

- CurtainUp Master Index of Reviews

- Musical Heaven

- StageSpecs.org

ROAD HOUSES

- Gammage [AZ]

- Golden Gate [CA]

- Curran [CA]

- Orpheum [CA]

- Community Center [CA]

- Civic [CA]

- Ahmanson [CA]

- Pantages [CA]

- Temple Hoyne Buell [CO]

- Palace [CT]

- Rich Forum [CT]

- Shubert [CT]

- Bushnell [CT]

- Chevrolet [CT]

- Broward Center [FL]

- Jackie Gleason [FL]

- Fox [GA]

- Civic Center [IA]

- Cadillac Palace [IL]

- Ford Center/Oriental [IL]

- The Bank of America Theatre [IL]

- Auditorium Theatre of Roosevelt University [IL]

- Kentucky Center [KY]

- France-Merrick [MD]

- Colonial [MA]

- Wilbur [MA]

- Charles [MA]

- Wang [MA]

- Wharton Center [MI]

- Whiting [MI]

- Fisher [MI]

- Masonic Temple [MI]

- Orpheum, State, and Pantages [MN]

- Fabulous Fox [MO]

- New Jersey PAC [NJ]

- Auditorium Center [NY]

- Proctors [NY]

- Shea's PAC [NY]

- BTI Center [NC]

- Blumenthal PAC [NC]

- Schuster PAC [OH]

- Playhouse Square [OH]

- Aronoff Center [OH]

- Ohio [OH]

- Victoria Theatre [OH]

- Birmingham Jefferson [OH]

- Merriam Theater [PA]

- Academy of Music [PA]

- Benedum Center [PA]

- Providence PAC [RI]

- Orpheum [TN]

- Hobby Center [TX]

- Music Hall [TX]

- Bass Hall [TX]

- Paramount [WA]

- Fox Cities PAC [WI]

- Marcus Center [WI]

- Weidner Center [WI]

FESTIVALS

- The New York International Fringe Festival

- The American Living Room Festival

- Summer Play Festival

- The New York Musical Theatre Festival

- Adirondack Theatre Festival

- NAMT: Festival of New Musicals

SPECIAL

- BC/EFA: Broadway Cares / Equity Fights AIDS

- The Actors' Fund

- Stage Directors and Choreographers Foundation

EDUCATION

- Google Shakespeare

- Actor Tips

- AACT

- ArtSearch

- Broadway Classroom

- Broadway Educational Alliance

- Camp Broadway

- Great Groups - New York Actors

- Theatre Communications Group (TCG)

- Theatre Development Fund (TDF)

- Off-Broadway Theater Information Center

UNIONS/TRADE

- AEA

- SAG

- AFTRA

- AGMA

- The League

- APAP

- Local 1

- ATPAM

- IATSE

- AFM

- AFM - Local 802

- Treasurers & Ticket Sellers Union

- DGA

- Dramatists Guild

- USA 829

- WGA, East

- WGA, West

- SSD&C

- AFL-CIO

- League of Professional Theatre Women

NYC NON-PROFITS

- Cherry Lane Theatre

- City Center

- Drama Dept.

- Ensemble Studio Theater

- Jean Cocteau Rep.

- Lark

- Lincoln Center Theater

- Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts

- Lucille Lortel Foundation

- Manhattan Theatre Club

- MCC

- Mint

- Pearl Theatre Company

- Public Theater

- Roundabout

- Second Stage

- Signature

- The Vineyard Theatre

- The York Theatre Company

REGIONAL

- Actors Theatre

- Alabama Shakespeare Festival

- Alley Theatre

- ACT

- American Musical Theatre in San Jose

- American Repertory

- Arena Stage

- Barrington Stage Company

- Bay Street Theatre

- Berkeley Rep

- Casa Manana

- Chicago Shakespeare Theater

- Cincinnati Playhouse

- CTC

- Dallas Summer Musicals

- Dallas Theater Center

- Denver Center

- George Street

- Goodman

- Guthrie

- Goodspeed

- Hartford Stage

- Hudson Stage Company

- Theatre de la Jeune Lune

- Kennedy Center

- La Jolla

- Long Wharf

- Lyric Stage

- Mark Taper Forum

- McCarter

- New Jersey Rep

- North Shore

- Old Globe

- Ordway

- Oregon Shakespeare

- Paper Mill

- Prince Music Theater

- The Rep (St. Louis)

- Sacramento Music Circus

- San Francisco Mime Troupe

- Seattle Rep

- Shakespeare Theatre Co. (DC)

- The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey

- South Coast Rep

- Steppenwolf

- Theater of the Stars (GA)

- Theater J (DC)

- Theater Under the Stars (TX)

- Trinity Rep

- Two River Theater Company

- Utah

- Victory Gardens

- Westport

- Williamstown

- Yale Rep

KEWL

The Trials, Tribulations, and Triumph of Jesus Christ Superstar from Hit Single to Concept Album and Broadway Premiere

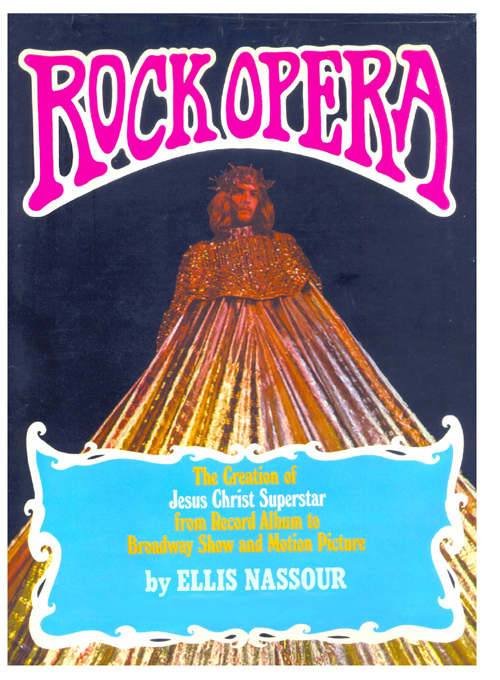

by Ellis Nassour

-

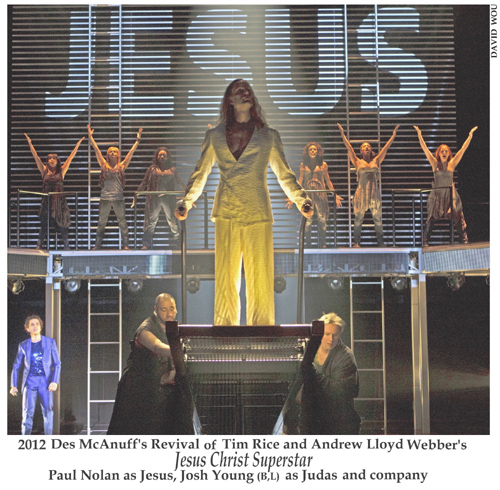

To coincide with the opening on Broadway of the acclaimed Des McAnuff and Stratford Shakespeare Festival's revival production of Tim Rice and Andrew Lloyd Webber's Jesus Christ Superstar, we present an excerpt, with added segues where needed, from Ellis Nassour's book Rock Opera: The Creation of Jesus Christ Superstar about the unusual and landmark path to success of the rock opera from a 45rpm single to the concept album that became a worldwide sensation.

Rock Opera explored the frustrations, missteps, and ultimate triumph of the landmark musical's journey from hit single to Tom O'Horgan's bizarre, controversial Broadway production, subsequent stagings in the U.K., Australia, and beyond, and Universal Pictures' screen adaptation directed by Norman Jewison. The rock opera has proven to stand the test of time with limitless productions worldwide, the most unusual one being an all-male Japanese production in the Kabuki style.

Rock Opera explored the frustrations, missteps, and ultimate triumph of the landmark musical's journey from hit single to Tom O'Horgan's bizarre, controversial Broadway production, subsequent stagings in the U.K., Australia, and beyond, and Universal Pictures' screen adaptation directed by Norman Jewison. The rock opera has proven to stand the test of time with limitless productions worldwide, the most unusual one being an all-male Japanese production in the Kabuki style.

"... November 4, 1969

Department heads of MCA-Decca Records, a division of Music Corporation of America - Universal Studios, converged to sample product and comment on how best to merchandise it... As the demos played, whatever spirit was present disappeared. There was a song from Decca's Nashville roster, but no one understood what it was about. Exec VP Jack Loetz arrived and seated himself next to Tony Martell, marketing and creative services VP.

As the demos played, whatever spirit was present disappeared. There was a song from Decca's Nashville roster, but no one understood what it was about. Exec VP Jack Loetz arrived and seated himself next to Tony Martell, marketing and creative services VP.

Most squirmed in their chairs or made snide remarks. Every once in a while Loetz would remind his staff: "This is the product that's selling. This is what's keeping our doors open!"

Some relief came from a studio-assembled band that had potential as a bubble-gum hit. Everyone was about to head back to their offices when VP international Richard Broderick stood up. "There's one more," he said quite matter-of-factly. "Something quite unusual. It's a record I've brought back from England....This is just a preview...It can be something monstrous. The new artist is Murray Head. This is his first record. The title is 'Superstar.'"

As the song played, the room became engrossed in alternating veins of confused conversation and excitement. The record ended. The room was hushed. Martell asked, "Well?" There was reluctance in speaking up. "We want your opinions," Loetz demanded."A record like that couldn't get any airplay" was one reply. Another said, "It's fantastic. Best thing we've had in months." Then there was the negative, "No one will touch it. People will come down on us. After all, Decca is a prestige label."

"Yeah," spoke another. "A prestige label that sadly needs a blockbuster hit." Another staffed piped up, "A song like that will offend everyone. We're crazy if we put it out!"...

Loetz, who was unsure about the record's possibilities himself, sat there with no reaction.

"The other labels don't know about it yet," Broderick pointed out. "It will be a Decca scoop! 'Superstar' is from a still unfinished rock opera titled Jesus Christ Superstar by two British youngsters, Tim Rice and Andrew Lloyd Webber. It is sung by Judas." He added that the project would be perhaps their most expensive ever...A department head blurted, "If we put that record out, every churchman in the country will stone us." Another lamented, "The stations aren't going to play it. All they're going to hear is 'Jesus, who are you? Jesus Christ, what have you sacrificed?'"

Martell interrupted, "There'll be some controversy, but young people will go for it. They're the ones buying records. It could be an underground smash. We could use a little controversy!"

After the meeting, Martell remained with Broderick. "Dick, I want it," said Martell. "It's not going to be easy," Broderick replied. "We're going to have a fight on our hands."

And they did.

The way the authors of Jesus Christ Superstar met befits a press agents dream of the typical old Hollywood story.

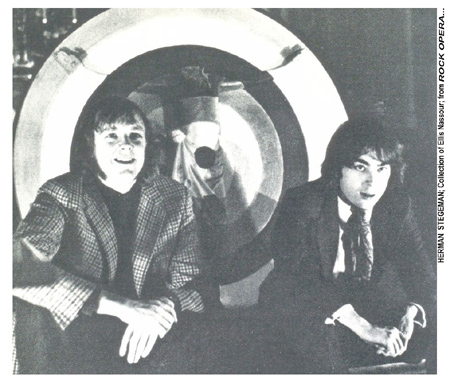

Tim Rice and Andrew Lloyd Webber met in Spring 1965. Tim was looking for a writing partner and a friend suggested he contact Andrew, some three-and-a-half years younger.

On receiving the letter, Andrew rang Tim at a law office where he was working - in preparation for becoming a solicitor. They chatted and two days later, Tim went to the Webber family flat in South Kennsington.

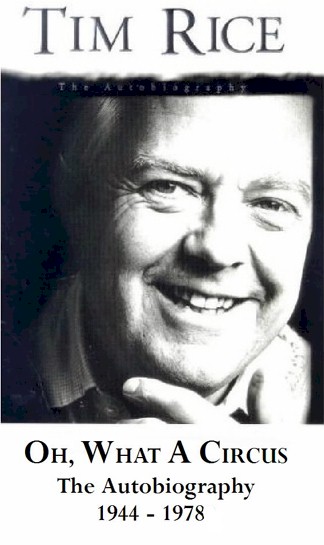

In his autobiography, Oh, What a Circus, 1944-1978, Tim wrote: "The boy who greeted me proved to be the acme of paradox. He oozed contradiction. Aspects of this were instantly apparent; he seemed at once awkward and confident; sophisticated and naïve; mature and childlike. Later I discovered that he was also humorous and portentous; innovative and derivative; loyal and cavalier; generous and self-centered; all these characteristics to the extreme." Tim's dad was a major with the Eighth Army in WWII and later worked for de Havilland Aircraft. Webber's father was a composer and, in the late 60s, director of the Royal College of Music. As a child he was trained to play the piano, violin, and French horn. By age six he was building toy theatres and writing opera.

Tim's dad was a major with the Eighth Army in WWII and later worked for de Havilland Aircraft. Webber's father was a composer and, in the late 60s, director of the Royal College of Music. As a child he was trained to play the piano, violin, and French horn. By age six he was building toy theatres and writing opera.

He had his first composition published when he was nine. Rice, although a big fan of the classics, by his teens was well versed in all aspects of the contemporary sounds and had traveled extensively, even living in Japan for a year when his father was stationed there. He attended religious school before entering university in the U.K.After a term of history studies at Oxford's Magdalen College, Webber left to study music at Guildhall and the Royal College of Music, intent on managing pop artists and arranging and conducting. Rice joined rock group Racket, delving "not too deeply," he quipped, "into writing pop lyrics."

The duo's collaboration began to pay off when they sold pop songs to recording artists, but there were no hits.

In 1965, they collaborated on The Likes of Us [never produced, but since released as an all-star concert album], a comedy about Thomas John Barnardo, a Victorian doctor, philanthropist, and humanitarian. In 1966, Rice became an assistant in EMI's music publishing division; and also produced fledgling rock groups.

...Their great desire was to have a project presented on the West End stage. A friend asked them to write a show for the school where he taught, and Rice and Webber hit upon the idea of turning to the Bible for their plot. The result was Joseph and His Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat, a rock cantana based on the biblical story of Jacob and Rachel' s first son who was sold into slavery by his brothers. Its popularity spread, and soon it was presented in schools around the country. A staging in St. Paul's Cathedral led to a recording for [British] Decca [no affiliation with MCA] and flattering press reviews.

Yet, the album didn't take off. Webber wrote real estate tycoon Sefton Myers, who had backed a musician friend of his and Rice's, to get him to fund a pop music museum. He included the Joseph album. Myers wasn't attracted to that idea but was interested in Webber and Rice working together. He set up a meeting with attorney/agent David Land.

They formed a partnership making it possible for the duo to concentrate on writing by providing a weekly allowance. When they made money, Meyers and Land would receive a hefty percentage. Rice was reluctant to sign on, but eventually came aboard.

While at the Royal College, Webber was speaking with an Anglican minister who suggested he write a musical on Christ's life. Not the standard fare but a composition that modern youth could identify with. At that time Webber just laughed, saying, "What a terrible idea! It'll never sell!"

[He] brought up the idea to Rice, and they considered it but instead set about putting the Richard the Lion-Hearted legend to music under the title Come Back, Richard, Your Country Needs You. It had one performance, but the duo recorded the title song for release as a 45.

They returned to the idea of the musical about Jesus, though they feared such an undertaking would be extremely controversial. "We knew we would have to be different to be interesting and exciting," said Rice. "We naturally considered rock with my background, and opera and with Andrew's knowledge of the classics. Then we had this idea. 'Why not combine the two?' The Who had caused quite a stir by calling their Tommy a rock opera. That's how it all came about."

Webber discussed the project with the Dean of St. Paul's, who offered encouragement but a warning that a pop treatment of Jesus' passion might rekindle anti-Semitic feelings. Rice felt that times had changed. "People had become more liberal and more intelligent about this sort of thing," he noted.

"Most everyone we spoke to thought it was a foolish idea," said Webber. "We didn't give up. Finally, we felt the time was right. It was a chance we decided to take. I don't think, with the sort of views expressed in the opera, we expected anybody would want to back us or record it."British Decca and other English labels passed. RCA replied with an emphatic "not interested."

Rice remembered an old friend, Alan Crowder, who was now at MCA-UK, just getting involved in the English scene but having considerable success with its first ventures. Crowder introduced Rice, Webber, and Land to Brian Brolly, a modish-dressing Irishman in his early 40s, who headed the English recording division. He flipped for the idea. According to Webber, "It was agreed that we'd first send up a flag to see whether the public would accept our approach." Then, in a bit of bravado and due to Brolly's enthusiasm, MCA commissioned the composition, gave Rice and Webber the go ahead and an advance.

He flipped for the idea. According to Webber, "It was agreed that we'd first send up a flag to see whether the public would accept our approach." Then, in a bit of bravado and due to Brolly's enthusiasm, MCA commissioned the composition, gave Rice and Webber the go ahead and an advance.

MCA, knowing it was a gamble, didn't offer generous terms. In fact, when they demanded publishing rights, Rice and Webber thought the deal proffered was close to usury but eventually signed.The story would cover Christ's last week on Earth as seen through the eyes of Mary Magdalene and apostle Judas Iscariot. Rice felt that since little is written of Judas in scripture, he would be a good character to write lyrics for. Their first tune was planned "as a tirade for Judas."

Webber had been working up many ideas for an appropriate song, and the myth goes that one night while in a London burger joint the melody came to him and he jotted it down on a napkin. Rice recounted that he wrote the lyrics while waiting for his mother to prepare lunch one Sunday - though he had given the song much thought.

Webber composed a simple three-chord structure, embellishing it with a chorus from a short-lived musical idea on King David.

"I knew the sort of questions I wanted Judas to ask," said Rice [in Oh, What a Circus] and by setting it in the Twentieth Century rather than in the First, the questions struck a contemporary chord."

The title was "Jesus Christ, Jesus Christ" until Rice saw a trade ad calling Tom Jones the world's Number One Superstar. Back to the drawing board. The lyric was rewritten, the title changed.

Preparations began in secret. "Superstar" would be sung by Judas near the end of the opera. He would materialize after hanging himself as "a sort of common man" - as the authors put it, "to ask a whole string of questions and, in a way, sum up the attitude of the whole opera."Webber did the orchestrations and music direction. That September, Rice and Webber laid down the tracks with Murray Head, a singer-actor-composer appearing in the London cast of Hair who was about to embark on a film career [Sunday, Bloody Sunday], whom Rice had worked with.

Webber demanded a lot and got what he wanted: a choir, a gospel group, and a 56-piece orchestra with full rock section [members of Joe Cocker's Grease Band]. The cost for producing the single was more than was allotted for most British albums."Superstar" was released as a single in November. A few MCA-UK executives referred to it as 'Brolly's Folly.' Brolly played the session tape for the visiting Richard Broderick, who felt the song and eventual rock opera would be a turning point for the label.

Word of MCA's acquisition got out. All sorts of rumors began circulating, culminating in a Daily Express story of April 12: "Beatle John Lennon has been asked to play Jesus Christ in a musical planned for presentation in St. Paul's Cathedral. And he wants his wife, Yoko Ono, to play Mary Magdalene."

Rice was quoted: "We feel Lennon would be ideal. We are bound to upset a few people, but we don't want to annoy anyone. He is sincere in his efforts for peace - at least he is trying to do something."That same day, The Evening News ran: "Beatle John Lennon and his wife, Yoko Ono, will not be taking part in the pop musical ... The organizers feel that Lennon is too much of a personality for the part of Christ and would divert attention from the part to himself."

In the end, there was no presentation, but Rice and Webber decided a relative unknown should play the role. Time was the first here to report that such an undertaking was a foot, but with the Lennon denials, nothing more was heard.

Since the record represented something special, a decision was made to give it special handling. The sleeve was a simple white one. On the front was a sketch of a God-like figure with the single-word title "Superstar" below. There was no mention of Jesus Christ, but information on the back cover carried the prophetic words "from the rock opera Jesus Christ now in preparation."

Nowhere was it indicated that the song was sung by Judas in the opera. Below Rice, Webber, and Head's names, the lyrics appeared. A short instrumental piece from the opera, the only other composition fully completed, "John 19:41," was the flip side.

In order to lessen cries that the record was a sacrilege and to give it some sort of official imprimatur, a quote from the St. Paul's Dean was printed across the top: "There are some people who may be shocked by this record. I ask them to listen to it and think again. It is a desperate cry. Who are you Jesus Christ? is the urgent enquiry, and a very proper one at that. The record probes some answers and makes some comparisons. The onus is on the listener to come up with his replies. If he is a Christian, let him answer for Christ. The singer says he only wants to know. He is entitled to some response."

Before Decca could worry about outraging Christian society, they had to worry about securing airplay. "Superstar" was shipped to distributors and radio stations the first Monday in December. Very little was heard of it after that. It hit the marketplace when it was flooded with Christmas product and stations were playing the Top 40 and holiday carols.

Broderick had the foresight to slip an advance copy to DJ Scott Muni at WNEW-FM, who played it several times during his shows. "Superstar" was a hit with Muni's "underground audience." Others tied up the switchboard with protest.In London, Rice and Webber appeared on David Frost's television show. When Head sang the tune and Frost mentioned it was from a forthcoming rock opera called Jesus Christ, the lines were jammed for nearly an hour with protest calls.

"That was about the sum total of the excitement the record stirred in England," laughed Rice.The record was picking up more and more FM airplay here. A story in Time helped...In several cities, such as New York, Miami, and Cleveland, stations were not only playing the record but following with a discussion group of local clergy.

"Superstar" was receiving tremendous response, particularly in countries whose population was predominantly Catholic, such as France, Italy, Spain, and Brazil. In England, the two BBC-controlled outlets banned the recording at first, but with the Armed Forces radio network and Radio Luxembourg programming it (and helping spur European sales), the BBC gave in."

"Superstar" was receiving tremendous response, particularly in countries whose population was predominantly Catholic, such as France, Italy, Spain, and Brazil. In England, the two BBC-controlled outlets banned the recording at first, but with the Armed Forces radio network and Radio Luxembourg programming it (and helping spur European sales), the BBC gave in."

Rice and Webber continued to make changes in their score, even as the sessions for the album were underway.

...Some of the musicians disagreed with the composers terming the work a rock opera. It was not opera, they said, and even though rock music was used, it was not rock. The composition was a merging of rock, classical, vaudeville, choral, and electronic pieces...

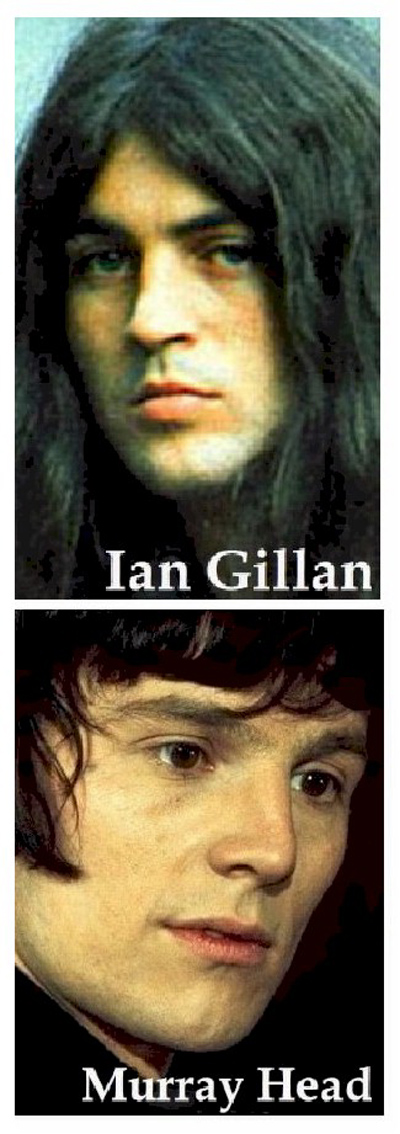

They never lost sight of the rock opera as a whole composition. Rice, who often mused that Jesus Christ Superstar might be his only chance for recognition, wanted to make sure the lyrics were understood and not lost in the throbbing music. Webber was also a perfectionist.For the role of Jesus, the composers chose Deep Purple singer/songwriter Ian Gillan, known for his wide vocal range and high-pitched screams. Yvonne Elliman was cast Mary Magdalene, a role she made into a career; with Barry Dennen as Pilate and, in the flamboyant role of King Herod, Mike d'Abo.

In July, all was finished. Total cost: $65,000...Jesus Christ Superstar took up four master tape reels, which included numerous out-takes. In toto, there were 60 sessions, 400 hours of recording time. MCA decided the rock opera was too long - even for the two-record set they were designing. Cuts were made... It was decided the English jacket art work was too garish and a new design was initiated for the U.S....Almost a year after the release of the single, the day of the album unveiling in the U.S. arrived. It was to be held in Decca's West 57th Street recording studios. Then VP Milt Gabler wondered out loud at a meeting: "Wouldn't it be great if the premiere could be held in a church?"

It was decided the English jacket art work was too garish and a new design was initiated for the U.S....Almost a year after the release of the single, the day of the album unveiling in the U.S. arrived. It was to be held in Decca's West 57th Street recording studios. Then VP Milt Gabler wondered out loud at a meeting: "Wouldn't it be great if the premiere could be held in a church?"

Everyone laughed, but Martell's eyes lit up..."You can't present a record like Jesus Christ Superstar in a church!" blurted one of those present.

Turns out you could. And, after a suggestion to present it at Oberammergau, the famed Bavarian village where Christ's passion is acted out every 10 years was voted down, they did.October 27, 1971, the preview was held at St. Peter's Lutheran Church, Lexington Avenue and 54th Street. [The original building is gone, but St. Peter's was reborn in an ultra-modern multi-level complex in the Citibank site.]

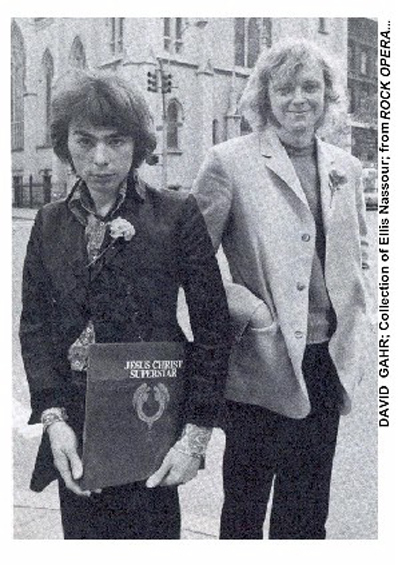

Rice and Webber had a relaxed lunch with the label's artist relations director at their hotel and then walked three blocks to St. Peter's. Webber was not happy with the reception the album received in London a week before. He was pessimistic about the whole thing and predicted a tremendous failure.

Rice was optimistic...[but] the boys were a bit flabbergasted by what they saw at the church. They thought taste had been taken a bit too far. An organist was playing Bach, the record executives wore white carnations in their lapels. Sprays of flowers were spread around the church. "This is going to be some bloody show," Rice observed.

They felt better when Time's photographer arrived and took them outside for a photo in the middle of Lexington Avenue.

Music critics were generally ecstatic, however, Jesus Christ Superstar wasn't everyone's pint of brew. "It borders on blasphemy and sacrilege," spew the Reverend Billy Graham. "It's historically and scriptually inaccurate and the Jewsish people have been maligned," stated respected New York Rabbi Marc Tannenbaum.

In the most interesting of all turnabouts, as the legend of Jesus Christ Superstar grew, those so violently anti the recording mellowed. The musical has gone on to be presented around the world and even staged in churches. The book goes on to deal with producer Robert Stigwood, coming aboard as producer with MCA, how Hal Prince might have been the director of Jesus Christ Superstar, how Frank Corsaro became diretor - then, in unusual circumstances was fired; hiring avant garde director Tom O'Horgan of Hair fame, authorized and unauthorized concerts of the work, and the path to Broadway.

The book goes on to deal with producer Robert Stigwood, coming aboard as producer with MCA, how Hal Prince might have been the director of Jesus Christ Superstar, how Frank Corsaro became diretor - then, in unusual circumstances was fired; hiring avant garde director Tom O'Horgan of Hair fame, authorized and unauthorized concerts of the work, and the path to Broadway.

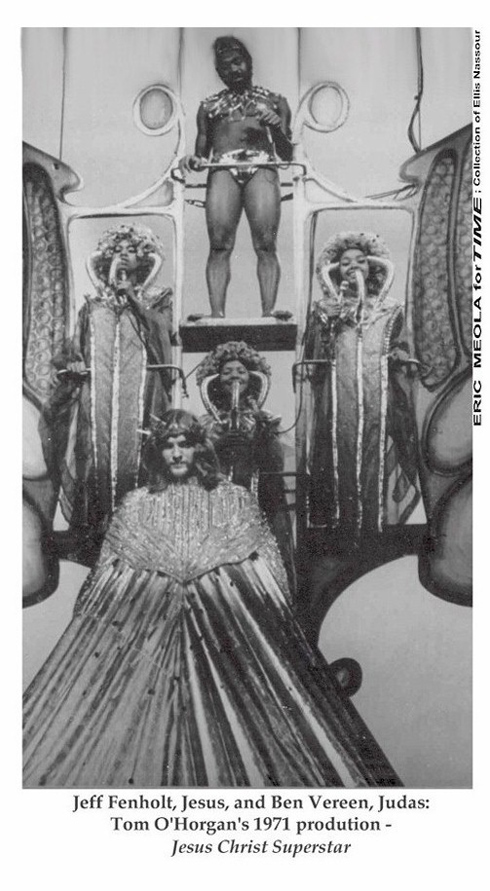

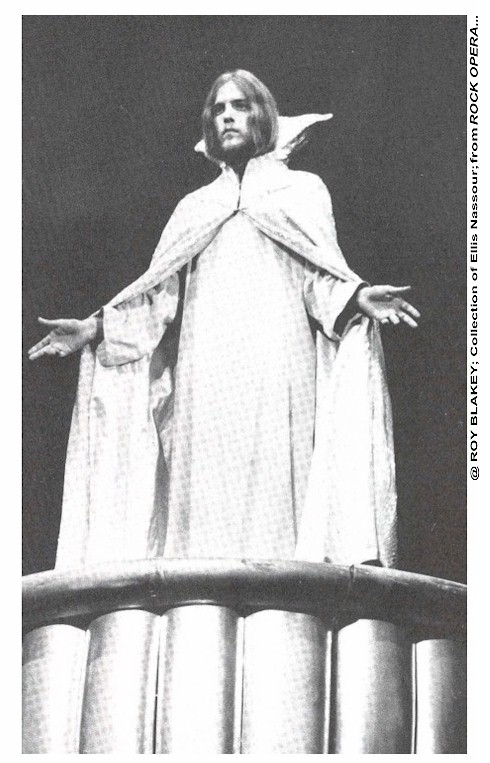

Jeff Fenholt was cast as Jesus, Ben Vereen as Judas, with Elliman and Dennen in the roles they created on record. Paul Ainsley played Herod.

The tremendous popularity of the album created a challenge for Broadway, one that had tremendous impact on sound design for the show, and on the future of theatre sound design, and its emerging aesthetic.

Webber, especially, felt the sound in the cavernous Mark Hellinger Theatre had to replicate the record sound. Furthermore, the show had a knowing producer, Robert Stigwood, who began his career with [Beatles manager] Brian Epstein.

Numerous sound problems arouse when it was decided to turn the orchestra pit into a recording studio. In the late 1950's when stereophonic sound was being touted, the pitch by labels was that stereo brought the listener into the middle of the music as in a live performance. Here was a live performance opting for recorded sound with sophisticated equipment attempting to create the feel and the tricks of "record" sound.

The sound system cost over $300,000: $200,000 for the original equipment, and another $100,000 for the alterations made by sound designer Abe Jacob. Since the scenery topped out at $129,000, and the costumes at $80,000, the show marked the first time sound design costs exceeded visual design. There were pitfalls with set pieces being built and delivered without ever measuring the load-in doors. They had to be rebuilt. The elevator that would bring Fenholt onstage would stick. The cross for the finale crucifixion, one of the first set pieces to use hydraulics to propel it forward, often didn't work.

There were pitfalls with set pieces being built and delivered without ever measuring the load-in doors. They had to be rebuilt. The elevator that would bring Fenholt onstage would stick. The cross for the finale crucifixion, one of the first set pieces to use hydraulics to propel it forward, often didn't work.

"If you can thing of something that didn't go wrong," joked set designer Robin Wagner, "please let me know what it was. On two occasions, Jeff fell, so we decided to have him run backstage and get on the cross by way of a ladder. At the end of the performance, a stagehand was supposed to have the ladder back so Jeff could make the curtain. You know stagehands. They're everywhere but where you need them. Things were so hectic a couple of times that Jeff got stranded and yelled some rather unChrist-like language to get attention."

The first preview was canceled while everyone got their ducks in order. October 12, 1971, Jesus Christ Superstar had a star-studded opening, complete with massive street protests. It played 711 performances and 13 previews; and was nominated for five Tony Awards, including Lighting, Costumes [by the brilliant Randy Barcelo] and Scenic Design. Sound was not a candidate, since no Tony category existed for sound [a sad state that continued until the American Theatre Wing created one in 2007].

October 12, 1971, Jesus Christ Superstar had a star-studded opening, complete with massive street protests. It played 711 performances and 13 previews; and was nominated for five Tony Awards, including Lighting, Costumes [by the brilliant Randy Barcelo] and Scenic Design. Sound was not a candidate, since no Tony category existed for sound [a sad state that continued until the American Theatre Wing created one in 2007].

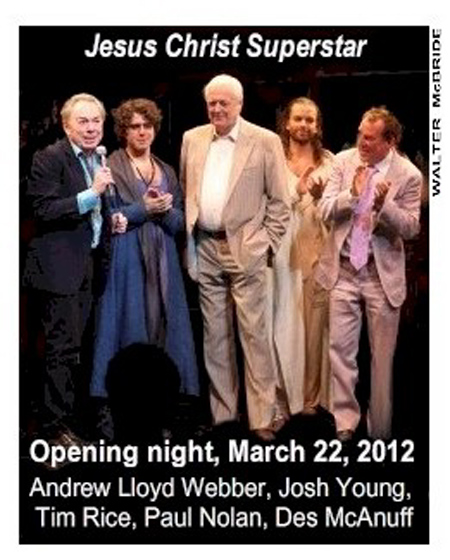

Though he initially kept his feelings private, it's no secret that Andew Lloyd Webber hated Tom O'Horgan's production and dreamed that one day there would be a production worthy of his and Rice's score.The latest revival of Jesus Christ Superstar, directed by Des McAnuff and first presented at Stratford Shakespeare Festival, opened on Broadway March 22, 2012. Paul Nolan [Jesus], Josh Young [Judas], Chilina Kennedy [Mary Magdalene], Tom Hewitt [Pontius Pilate], and Bruce Dow [King Herod].

Ellis Nassour is an international media journalist, and author of Honky Tonk Angel: The Intimate Story of Patsy Cline, which he has adapted into a musical for the stage. Visit www.patsyclinehta.com.

He can be reached at [email protected]

Why are you looking all the way down here?

For more articles by Ellis Nassour, click the links below!

Previous: The Oscars Are Coming! Wait! They're (Almost) Here; Brian d'Arcy James on SMASH; Some Phantom with Your Popcorn; Mark Your Calendar

Next: Death of a Salesman and Notes from Elia Kazan; Last Chance: Encores' Pipe Dream; Berlin's American Musical Theater; Remembering a Great Tenor; Celebrating Capezio; Titanic 3-D; Dickens on PBS; New to DVD/CD; Summertime; So Long, Farewell

Or go to the Archives

[Broadway Ad Network]

[Broadway Ad Network]

If you would like to contact us, you can email us at feedback@

broadwaystars.com

[Broadway Ad Network]

[Broadway Ad Network]

- July 15: Harry Connick, Jr. in Concert on Broadway - Neil Simon

- Sept. 28: Brief Encounter - Studio 54

- Sept. 30: The Pitmen Painters - Samuel J. Friedman Theatre

- Oct. 3: Mrs. Warren's Profession - American Airlines Theatre

- Oct. 7: Time Stands Still - Cort Theatre

- Oct. 12: A Life In The Theatre - Schoenfeld Theatre

- Oct. 13: Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson - Bernard Jacobs Theatre

- Oct. 14: La Bete - The Music Box Theatre

- Oct. 21: Lombardi - Circle In The Square

- Oct. 25: Driving Miss Daisy - John Golden Theatre

- Oct. 26: Rain - A Tribute To The Beatles On Broadway - Neil Simon Theatre

- Oct. 31: The Scottsboro Boys - Lyceum Theatre

- Nov. 4: Women On The Verge Of A Nervous Breakdown - Belasco Theatre

- Nov. 9: Colin Quinn Long Story Short - Helen Hayes Theatre

- Nov. 11: The Pee-Wee Herman Show - Stephen Sondheim Theatre

- Nov. 13: The Merchant of Venice - The Broadhurst Theatre

- Nov. 14: Elf - Al Hirschfeld Theatre

- Nov. 18: A Free Man Of Color - Vivian Beaumont Theater

- Nov. 21: Elling - Ethel Barrymore Theatre

- Dec. 9: Donny & Marie: A Broadway Christmas - Marquis Theater

- Jan. 13: The Importance of Being Earnest - American Airlines Theatre

- Mar. 3: Good People - Samuel J. Friedman Theatre

- Mar. 6: That Championship Season - Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre

- Mar. 11: Kathy Griffin Wants a Tony - Belasco

- Mar. 17: Arcadia - Barrymore Theatre

- Mar. 20: Priscilla Queen Of The Desert The Musical - The Palace Theatre

- Mar. 22: Ghetto Klown - Lyceum Theatre

- Mar. 24: The Book Of Mormon - Eugene O'Neill Theatre

- Mar. 27: How To Succeed In Business Without Really Trying - Al Hirschfeld Theatre

- Mar. 31: Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo - Richard Rodgers Theatre

- Apr. 7: Anything Goes - Stephen Sondheim Theatre

- Apr. 10: Catch Me If You Can - The Neil Simon Theatre

- Apr. 11: The Motherf**ker with the Hat - Gerald Schoenfeld Theatre

- Apr. 14: War Horse - Vivian Beaumont Theater

- Apr. 17: Wonderland: A New Alice. A New Musical Adventure. - Marquis Theatre

- Apr. 19: High - Booth Theatre

- Apr. 20: Sister Act - The Broadway Theatre

- Apr. 21: Jerusalem - Music Box

- Apr. 24: Born Yesterday - Cort Theatre

- Apr. 25: The House of Blue Leaves - Walter Kerr Theatre

- Apr. 26: Fat Pig - Belasco Theatre

- Apr. 27: Baby It's You! - Broadhurst Theatre

- Apr. 27: The Normal Heart - Golden Theater

- Apr. 28: The People in the Picture - Studio 54

- Apr. 28: The End of The Season

- Jun. 12: The 65th Annual Tony Awards - Beacon Theatre

- June 14: Spider-Man, Turn Off The Dark - Foxwoods Theater

- June 21: Master Class - Samuel J. Friedman