[Broadway Ad Network]

[Broadway Ad Network]

TICKET / INFO

- StudentRush

- New York Show Tickets

- Givenik.com

- Telecharge.com

- Ticketmaster.com

- Group Sales Box Office

- Frugal TheaterGoer

- Broadway for Broke People

- Playbill's Rush/Lottery/SR

- Seating Charts

COMMUNITY

NEWS

- Back Stage

- Bloomberg

- Broadway.com

- BroadwayWorld

- Entertainment Weekly

- NYTheatre.com

- New York Magazine

- The New York Daily News

- The New York Post

- The New York Times

- The New Yorker

- Newsday

- NiteLife Exchange

- Playbill

- Show Business Weekly

- The Star-Ledger

- Talkin'Broadway

- TheaterMania.com

- Time Out New York

- American Theatre Magazine

- Theatre Development Fund (TDF)

- Best of Off-Broadway

- The Village Voice

- Variety

- The Wall Street Journal

- Journal News

REVIEWS

- The New York Times

- Variety

- New York Post

- NY1

- Aisle Say

- CurtainUp

- DC Theatre Scene

- Show Showdown

- Stage and Cinema

- StageGrade

- Talk Entertainment

- TotalTheater.com

- Off-Off Broadway Review

- TheaterOnline.com

- TheaterScene.net

- TheaterNewsOnline.com

WEST END

- The Stage

- 1st 4 London Theatre Tickets

- Book Your Theatre Tickets

- Compare Theatre Tickets.co.uk

- Theatre.com

- Whatsonstage.com [UK]

- ATW - London

- Musical Stages [UK]

- Albemarle of London

- Londontheatre.co.uk

- Google News

- Show Pairs

- ILoveTheatre.com

- The Official London Theatre Guide

- UK Tickets

BOSTON

CHICAGO

LA/SF

COLUMNS

- Peter Bart

- Andrew Cohen

- Ken Davenport

- Tim Dunleavy

- Peter Filichia

- Andrew Gans

- Ernio Hernandez

- Harry Haun

- Chad Jones

- Chris Jones

- James Marino

- Joel Markowitz

- Matthew Murray

- Michael Musto

- Ellis Nassour

- Tom Nondorf

- Richard Ouzounian

- Michael Portantiere

- Rex Reed

- Michael Riedel

- Frank Rizzo

- Richard Seff

- Frank Scheck

- Mark Shenton

- John Simon

- Robert Simonson

- Steve on Broadway (SOB)

- Steven Suskin

- Terry Teachout

- Theater Corps

- Elisabeth Vincentelli

- Hedy Weiss

- Matt Windman

- Linda Winer

- Matt Wolf

PODCAST

RADIO

TV

- Theater Talk

- BlueGobo.com

- Classic Arts Showcase

- American Theatre Wing Seminars

- Women in Theatre

- NY1

- WCBS [2]

- WNBC [4]

- FOX [5]

- WABC [7]

- WWOR [9]

- WPIX [11]

- Channel 13

- Hulu

- YouTube

AWARDS

- Tony Central

- Oscar Central

- Tony Awards

- Drama Desk Awards

- The Drama League Awards

- Lortel Awards

- Academy Awards

- Emmy Awards

- Grammy Awards

- GoldDerby

DATABASE

- Internet Broadway Database

- Internet Off-Broadway Database

- Internet Movie Database

- Internet Theatre Database

- Musical Cast Album Database

- [CastAlbums.org]

- Show Music on Record Database (LOC)

- CurtainUp Master Index of Reviews

- Musical Heaven

- StageSpecs.org

ROAD HOUSES

- Gammage [AZ]

- Golden Gate [CA]

- Curran [CA]

- Orpheum [CA]

- Community Center [CA]

- Civic [CA]

- Ahmanson [CA]

- Pantages [CA]

- Temple Hoyne Buell [CO]

- Palace [CT]

- Rich Forum [CT]

- Shubert [CT]

- Bushnell [CT]

- Chevrolet [CT]

- Broward Center [FL]

- Jackie Gleason [FL]

- Fox [GA]

- Civic Center [IA]

- Cadillac Palace [IL]

- Ford Center/Oriental [IL]

- The Bank of America Theatre [IL]

- Auditorium Theatre of Roosevelt University [IL]

- Kentucky Center [KY]

- France-Merrick [MD]

- Colonial [MA]

- Wilbur [MA]

- Charles [MA]

- Wang [MA]

- Wharton Center [MI]

- Whiting [MI]

- Fisher [MI]

- Masonic Temple [MI]

- Orpheum, State, and Pantages [MN]

- Fabulous Fox [MO]

- New Jersey PAC [NJ]

- Auditorium Center [NY]

- Proctors [NY]

- Shea's PAC [NY]

- BTI Center [NC]

- Blumenthal PAC [NC]

- Schuster PAC [OH]

- Playhouse Square [OH]

- Aronoff Center [OH]

- Ohio [OH]

- Victoria Theatre [OH]

- Birmingham Jefferson [OH]

- Merriam Theater [PA]

- Academy of Music [PA]

- Benedum Center [PA]

- Providence PAC [RI]

- Orpheum [TN]

- Hobby Center [TX]

- Music Hall [TX]

- Bass Hall [TX]

- Paramount [WA]

- Fox Cities PAC [WI]

- Marcus Center [WI]

- Weidner Center [WI]

FESTIVALS

- The New York International Fringe Festival

- The American Living Room Festival

- Summer Play Festival

- The New York Musical Theatre Festival

- Adirondack Theatre Festival

- NAMT: Festival of New Musicals

SPECIAL

- BC/EFA: Broadway Cares / Equity Fights AIDS

- The Actors' Fund

- Stage Directors and Choreographers Foundation

EDUCATION

- Google Shakespeare

- Actor Tips

- AACT

- ArtSearch

- Broadway Classroom

- Broadway Educational Alliance

- Camp Broadway

- Great Groups - New York Actors

- Theatre Communications Group (TCG)

- Theatre Development Fund (TDF)

- Off-Broadway Theater Information Center

UNIONS/TRADE

- AEA

- SAG

- AFTRA

- AGMA

- The League

- APAP

- Local 1

- ATPAM

- IATSE

- AFM

- AFM - Local 802

- Treasurers & Ticket Sellers Union

- DGA

- Dramatists Guild

- USA 829

- WGA, East

- WGA, West

- SSD&C

- AFL-CIO

- League of Professional Theatre Women

NYC NON-PROFITS

- Cherry Lane Theatre

- City Center

- Drama Dept.

- Ensemble Studio Theater

- Jean Cocteau Rep.

- Lark

- Lincoln Center Theater

- Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts

- Lucille Lortel Foundation

- Manhattan Theatre Club

- MCC

- Mint

- Pearl Theatre Company

- Public Theater

- Roundabout

- Second Stage

- Signature

- The Vineyard Theatre

- The York Theatre Company

REGIONAL

- Actors Theatre

- Alabama Shakespeare Festival

- Alley Theatre

- ACT

- American Musical Theatre in San Jose

- American Repertory

- Arena Stage

- Barrington Stage Company

- Bay Street Theatre

- Berkeley Rep

- Casa Manana

- Chicago Shakespeare Theater

- Cincinnati Playhouse

- CTC

- Dallas Summer Musicals

- Dallas Theater Center

- Denver Center

- George Street

- Goodman

- Guthrie

- Goodspeed

- Hartford Stage

- Hudson Stage Company

- Theatre de la Jeune Lune

- Kennedy Center

- La Jolla

- Long Wharf

- Lyric Stage

- Mark Taper Forum

- McCarter

- New Jersey Rep

- North Shore

- Old Globe

- Ordway

- Oregon Shakespeare

- Paper Mill

- Prince Music Theater

- The Rep (St. Louis)

- Sacramento Music Circus

- San Francisco Mime Troupe

- Seattle Rep

- Shakespeare Theatre Co. (DC)

- The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey

- South Coast Rep

- Steppenwolf

- Theater of the Stars (GA)

- Theater J (DC)

- Theater Under the Stars (TX)

- Trinity Rep

- Two River Theater Company

- Utah

- Victory Gardens

- Westport

- Williamstown

- Yale Rep

KEWL

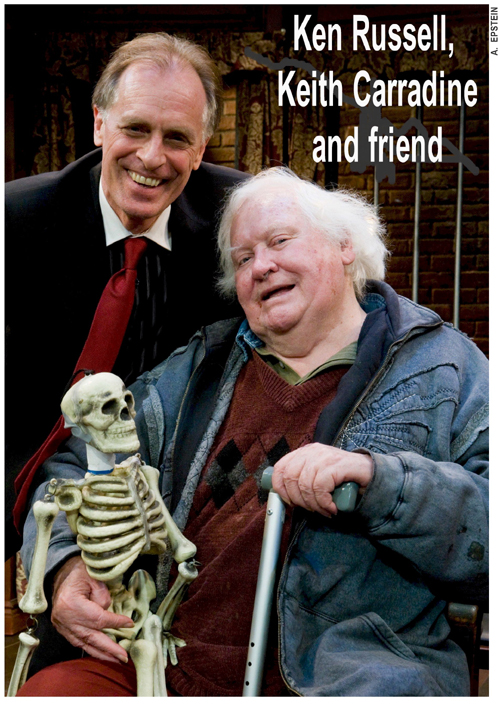

Ken Russell Makes Stage Directorial Debut with Psycho Drama Mindgame

by Ellis Nassour

-

"Insanity is just a state of mind" is a tagline of Anthony Horowitz's sexually-loaded psycho drama farce Mindgame, playing at the Soho Playhouse [15 Vandam Street, between Sixth Avenue and Varick Street]. The director is Ken Russell. Yes! That Ken Russell, making his New York and stage debut as a play director. And no one can make do with sexually-loaded psycho drama like Russell, who also has a bit of a reputation for being flamboyant and outrageous.Recently, in the U.K., Russell was on the TV reality show Celebrity Big Brother. "I didn't think of it at the time but," he laughs during a break in rehearsals prior to last night's opening, "all that intrigue and those different personalities going at each other sort of prepared me for directing a play set in an insane asylum."

Russell has acted, danced, written, produced, directed TV concerts [Sarah Brightman, Diva; Andrew Lloyd Webber], operas and, of course, has directed classic and controversial films. But, at 81, he's waited a long time to direct a play.

"Operas are plays with music," he explains. "I think when you establish a niche, such as directing films, you're not at the top of producers' lists to direct a play. Mindgame came to me in a circuitous way, through Lee Godart, who's one of the three actors.

"By the end of Act I, I was ready for a large scotch," he continues. "By the last page, I had finished the bottle. It was the scariest script I'd ever read. It caught my fancy. I don't do anything I don't like, ever. I found it intriguing and fascinating and thought I could bring something to it."

He says he liked Horowitz's ploy of making Act One so "drop-dead dramatic and tense with a surprise every five minutes" and Act Two so hilarious. It's a laugh-a-minute horror play."

Horowitz, a horror writer known for his Alex Rider series, also created the hugely popular, BAFTA-award winning TV series, Foyle's War.

Mindgame ran on the West End in 2000 following a 10-month sit-down in a regional and two-year tour. It tells of a crime novelist's attempt to get the head shrink at an asylum for the criminally insane to allow him to interview a serial killer who killed his father. But are the sane the insane or vice versa? In fact, is anything the way it seems?

Through a series of lies and manipulated memories, dark secrets are revealed. There's one recently alive skeleton in the doc's office and plenty waiting just outside the door -- or is that a cupboard? And what's with the portrait that can't make up what gender it wishes to be, to say nothing of the nurse in the tight-fitting white mini worthy of a porn film set-up.

Though Russell is usually most comfortable "painting on large canvases," the stage at the Soho is literally postage stamp-size. "It all takes place in a psychiatrist's office, so it's self-contained and confined to begin with. The theatre is rather intimate, too, which makes the play accessible to the audience."

He pointed out the main advantage in directing a play as opposed to a film "is that in the former you can go from start to finish every time in rehearsals. This allows the characters to develop naturally and in the moment, as one dramatic incident follows another and pushes them to grow organically."

He adds, "Films, for logistical reasons, are generally shot out of sequence, which is not only tough on the actors but also the director."

As he contemplated Mindgame for Off Broadway, he began a search for his leading man. Keith Carradine got wind of the project and contacted Russell.

"I wasn't as familiar with Keith's work as most Americans are," states the director. "He was anxious to do the play and sent me a DVD of clips, which confirmed in my mind if this guy wants to do it, I better grab him. In addition to films like Pretty Baby, The Duellists and Nashville* he's done quite a few of horror films and thrillers on the quiet."

* Carradine penned "I'm Easy" for the film and won an Oscar and Golden Globe for Best Original Song.

In Mindgame, Carradine has a field day with some very broad acting, channeling, it seems, Cary Grant, David Niven and Prince Philip. "Now that you mention it, right on," Russell laughs. "It could be worse, couldn't it?"

The play marks the Altman alum's first New York stage appearance since his July 2006 return to Broadway [after being Tony and Drama-Desk nominated for 1991's Will Rogers Follies] in the musical Dirty Rotten Scoundrels, replacing John Lithgow.

[Trivia: Carradine, who's the father of Martha Plimpton, made his Broadway debut as a replacement cast member in the original Hair, which brought him to Joseph Papp's attention and making his Off Bway debut at the Public in 1979's Wake Up, It's Time to Go to Bed, opposite Ellen Greene].

Mindgame also stars Lee Godart, an actor of some acclaim in France, here on TV soaps and in regional theatre; and Kathleen McNenny [Mrs. Milcote, Coram Boy; and for Roundabout, The Constant Wife, After the Fall].

On arrival in New York and finally ensconced in a flat on Bleecker Street, he had a time getting used to the early morning sanitation trucks doing their rounds. "I wanted to use that little doll and some pins on them, but now I seem to out sleep them. The cacophony of the sounds of New York life eventually becomes a sort of symphony of unsurpassed sweetness. I think the thick wads of wax I put in my ears and the dressing gown I put over my head have helped."

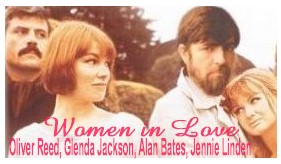

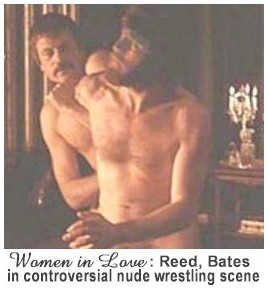

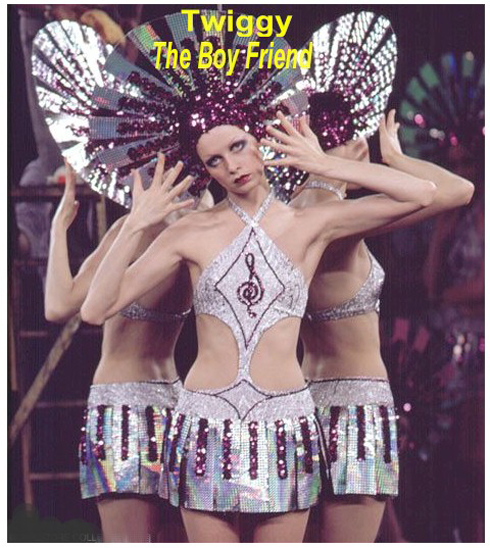

Known as Britain's "enfant terrible" of cinema, Russell directed the acclaimed Women in Love [1969, BAFTA and Oscar-nominated for director], The Music Lovers [1970], The Devils (1971), The Boy Friend (1971], Mahler [1974, Cannes Golden Palm-nominated for director], Tommy [1975], Lisztomania [1975], Valentino [1977], Altered States [1980] and Crimes of Passion [1984].

Russell's film adaptation of The Boy Friend is one of the most visually-stunning films of all time. "That one was such a joy to do that I just decided to have a lot of fun. It is pure escapism, and it turned out rather well."

Reminiscing, he says that there was one film "that maybe wasn't such a good idea." He takes a quick pause and adds, "Maybe a couple! I've been a critic's darling and a not-so-darling. But most of them are dead and I'm still going."

Russell met ALW and Tim Rice in the late 70s. He was to do the film adaptation of Evita, which starred Elaine Paige on the West End. She was ALW and Rice's choice for the screen, but Russell had Liza Minnelli, still riding high following her Oscar win for Cabaret, come in to audition. He was so mesmerized by her test that he refused to go forward on the film without her. Production was halted.

Russell states he's "never been afraid of being ridiculed. I'm not an understated director. I go the other way. I know my films upset people. I want to upset them. Life is too short to make films one doesn't like. My work is meant to be constructive and illuminating, but I'd rather gamble than play it safe. If I err, and admittedly I have, I can say that I tried to get it right."

That said, he notes that he would never do a violent, disturbing film like The Devils, which he considers his masterpiece. Though never released in the U.K. or here as Russell intended, it was one of the most controversial and top films of the 70s. It was called "provocative," "brilliant," "disturbing," "brilliant" and a "crazed exercise in Grand Guignol."

Britian's Evening Standard critic Alexander Walker called it "monstrously indecent" in a TV confrontation with Russell, who grabbed a copy of the paper, rolled it up and hit him over the head.

The Devils has become a cult favorite, especially at Halloween. Opulenty set in 17th Century, it starred Vanessa Redgrave as a sexually-obsessed nun and Oliver Reed as a priest in a devil-possessed nunnery caught up in Cardinal Richelieu's power-hungry attempt to control France.

He's been called the English Fellini and Orson Welles. "But," asks Russell, "do you know what Fellini was dubbed?" The Italian Ken Russell? "That's right," he beams.

He says he's not only outlived most of his critics, and that he takes care of the ones still around "with this little doll and a bunch of pins. What more do I need."

Every step of the way, for better and worse, Russell's always done it his way. He went from being acclaimed and very bankable to controversial and not so bankable.

Russell credits his love of classical music as the path that led him to film. "At the end of World War II, where I was in the Merchant Navy, I had a bit of a nervous breakdown," he reveals. "While I was recovering, Mum would put on the radio while she Hoovered around the chair where I sat gazing into space.

"One day I heard something that shook me up and woke me up," he continues. "It got me on my bicycle and peddling furiously to the record shop saying do you have Tchaikovsky's D Minor Piano Concerto? I played it over and over, and the next day I was back to buy more by this Tchaikovsky fellow. That led me to another Russian, Rimsky-Korsakov. I later found out they didn't like each other."

Eventually, Russell explained he went through all the classical composers "and each time I played their music, I saw pictures and couldn't stop seeing them. That was the beginning and my sort of intro to my dream of putting those images on the screen. After many starts and stops - I was a ballet dancer, a photographer, an actor, I saved up enough money to make home movies. That got me into the BBC, where I was encouraged to do programs on my hobbies. Mine was music."

In the late 50s with his work for the BBC TV's Monitor, he began to reshape the documentary tradition.

Once he made the leap into films, things didn't always go according to plan. There came a time where some of cinematic instincts made it difficult to get the next picture financed.

"I won't say that's not true, but I think the real culprit was that I chose not to move to Hollywood."Adds Russell, "I was brought up in Southhampton, near the New Forest, which is a magical place of pastures and heaths with a weird spirit, and I didn't want to move to Hollywood. Most producers there, unless they can have breakfast, lunch, tea and dinner with you, aren't interested. It was something I resisted."

He considers Glenda Jackson and Oliver Reed the actors he enjoyed working with most.

With a keen eye and a penchant for flamboyance and eroticism, Russell gained international acclaim with his feature film adaptation of DH Lawrence's Women in Love.

"When Glenda was cast for Women in Love, I'd never heard of her," he reveals. "I found myself watching her varicose veins more than her face, and only later what a magnificent screen personality she was. She was puzzling. Sometimes she looked plain ugly, sometimes just plain and sometimes the most beautiful creature one had ever seen."

It's rare for a director to name an actor he didn't particularly enjoy working with, but Russell is not that director. "With William Hurt in Altered States, I found I was his analyst for six months. It wasn't the part he talked constantly about, nor was he asking for guidance. He just ran on with all this crap about what a terrible thing being a billionaire was after being born into poverty. When my wife and I told him to cut the crap, he was stunned, but after that he was actually quite human."

It's no secret that Russell and Paddy Chayefsky, the Altered States screenwriter, clashed. "Paddy had never been involved with a director who wasn't malleable. But, in my case, he would make suggestions and I would listen courteously - and then disagree. He also kept interfering with the actors."

And that is something Ken ell never does? "Not like he did! The actors and I collaborate. I'll at least listen to anyone who has an idea."

He adds that on his films, there's no ad lib. "The script is as tight as a drum. I have every shot in my head before I shoot. I don't do a lot of cover [several shots of the same scene]. There's a right way to do it and I do it in what I consider to be the right way."

Russell is in moderately good health, except for a weight problem and recent surgery, which resulted in a metal knee cap. "I was well on my way to being totally mobile when I fell on the bloody thing and exaberated the situation. So, for a while, I'm hobbling along with a cane."

What next? Broadway? "Who knows," he quips. "Wouldn't be bad, would it?" Though he never been asked to direct at the Metropolitan Opera, he would like to put on Mindgame there.Mindgame, the sexually-loaded psycho drama? "Yes," he replies. "I'd write the libretto and lyrics and, since I can't write or read music, have John Corigliano [Altered States] compose the score."

But, in the immediate future, on his return to the U.K., Russell and wife [Number Four] Lisi will be back into movies. The first priority will be completing post-production on Moll Flanders, which features Barry Humphries as Madame Needham.

There will be more low-budget films, and his self-financed "home movies," such as Revenge of the Elephant Man and The Fall of the Louse of Usher, which he gets done with the help of friends "by giving them a good dinner with plenty of wine."

Up next is, from Russell's description, quite an interesting piece, Brave Tart vs. the Lock Ness Monster.

Ellis Nassour is an international media journalist, and author of Honky Tonk Angel: The Intimate Story of Patsy Cline, which he has adapted into a musical for the stage. Visit www.patsyclinehta.com.

He can be reached at [email protected]

Why are you looking all the way down here?

For more articles by Ellis Nassour, click the links below!

Previous: Tour de Forces; Nostalgia King Honored; Dancers Salute Broadway Musicals; Controversial Mormon Drama; American Buffalo Behind-the-Scenes; Met Museum Retrospective; Marilyn Maye on Stage and Screen

Next: Billy Elliot Pirouettes into a Hit; King David; Broadway Unplugged, Character Actor as Character; Encores! Returns; More

Or go to the Archives

[Broadway Ad Network]

[Broadway Ad Network]

If you would like to contact us, you can email us at feedback@

broadwaystars.com

[Broadway Ad Network]

[Broadway Ad Network]

- July 15: Harry Connick, Jr. in Concert on Broadway - Neil Simon

- Sept. 28: Brief Encounter - Studio 54

- Sept. 30: The Pitmen Painters - Samuel J. Friedman Theatre

- Oct. 3: Mrs. Warren's Profession - American Airlines Theatre

- Oct. 7: Time Stands Still - Cort Theatre

- Oct. 12: A Life In The Theatre - Schoenfeld Theatre

- Oct. 13: Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson - Bernard Jacobs Theatre

- Oct. 14: La Bete - The Music Box Theatre

- Oct. 21: Lombardi - Circle In The Square

- Oct. 25: Driving Miss Daisy - John Golden Theatre

- Oct. 26: Rain - A Tribute To The Beatles On Broadway - Neil Simon Theatre

- Oct. 31: The Scottsboro Boys - Lyceum Theatre

- Nov. 4: Women On The Verge Of A Nervous Breakdown - Belasco Theatre

- Nov. 9: Colin Quinn Long Story Short - Helen Hayes Theatre

- Nov. 11: The Pee-Wee Herman Show - Stephen Sondheim Theatre

- Nov. 13: The Merchant of Venice - The Broadhurst Theatre

- Nov. 14: Elf - Al Hirschfeld Theatre

- Nov. 18: A Free Man Of Color - Vivian Beaumont Theater

- Nov. 21: Elling - Ethel Barrymore Theatre

- Dec. 9: Donny & Marie: A Broadway Christmas - Marquis Theater

- Jan. 13: The Importance of Being Earnest - American Airlines Theatre

- Mar. 3: Good People - Samuel J. Friedman Theatre

- Mar. 6: That Championship Season - Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre

- Mar. 11: Kathy Griffin Wants a Tony - Belasco

- Mar. 17: Arcadia - Barrymore Theatre

- Mar. 20: Priscilla Queen Of The Desert The Musical - The Palace Theatre

- Mar. 22: Ghetto Klown - Lyceum Theatre

- Mar. 24: The Book Of Mormon - Eugene O'Neill Theatre

- Mar. 27: How To Succeed In Business Without Really Trying - Al Hirschfeld Theatre

- Mar. 31: Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo - Richard Rodgers Theatre

- Apr. 7: Anything Goes - Stephen Sondheim Theatre

- Apr. 10: Catch Me If You Can - The Neil Simon Theatre

- Apr. 11: The Motherf**ker with the Hat - Gerald Schoenfeld Theatre

- Apr. 14: War Horse - Vivian Beaumont Theater

- Apr. 17: Wonderland: A New Alice. A New Musical Adventure. - Marquis Theatre

- Apr. 19: High - Booth Theatre

- Apr. 20: Sister Act - The Broadway Theatre

- Apr. 21: Jerusalem - Music Box

- Apr. 24: Born Yesterday - Cort Theatre

- Apr. 25: The House of Blue Leaves - Walter Kerr Theatre

- Apr. 26: Fat Pig - Belasco Theatre

- Apr. 27: Baby It's You! - Broadhurst Theatre

- Apr. 27: The Normal Heart - Golden Theater

- Apr. 28: The People in the Picture - Studio 54

- Apr. 28: The End of The Season

- Jun. 12: The 65th Annual Tony Awards - Beacon Theatre

- June 14: Spider-Man, Turn Off The Dark - Foxwoods Theater

- June 21: Master Class - Samuel J. Friedman