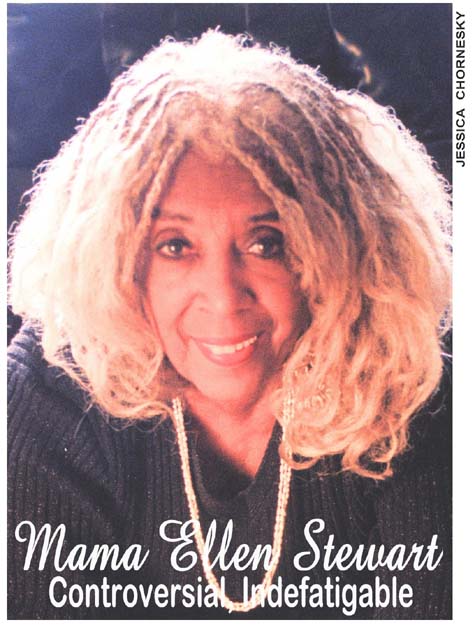

Ellen Stewart, the much acclaimed and venerated founder and director of La MaMa E.T.C., which celebrates its 47th Anniversay in October. The company occupies a unique presence not only in the storied world of Off Off and Off Broadway but in international theatrical circles. Just as her name is synonymous with controversy and controversial productions, it ranks at the top of the list of daring and avant garde theater.

Make no mistake about it, experimentation, politics, risk-taking and challenging artistic boundaries and the public or various city administration's definition of decency have been the focus of work created at La MaMa.

The stories about Ellen Stewart, her struggles against censorship and the establishment are legendary and could fill a couple of books. She's been arrested and ridiculed and harangued in news articles. The problem is you don't how many of these stories are true and which have been exaggerated. So to get to the bottom of things, it was wise to go to the "horse's mouth."

Ms. Stewart, now in her 80s and going as fast as she can here and overseas, often in four directions at the same time, doesn't grant many interviews. But when she does, you can bet it's going to freewheeling, informative and a helluva lot of fun.

Her Greenwich Village loft apartment on the top floor of the La MaMa complex on East Fourth Street, between First and Second Avenues, is filled with photos, books, plays and a vast array of music and theater memorabilia; so vast, in fact, you might wonder if this lady could put her fingers on something she wants when she wants it or when some inquiring mind asks a question about that something.

Worry not because, like Joe Franklin in his office of nostalgic memorabilia that gives "piles of clutter" a new definition, Mama, as anyone remotely close to her calls Ms. Stewart, knows exactly where it is, how long it's been there and who's touched it last. And you better ask before you touch it!

The company's philosophy can be summed up in their mission statement: "La MaMa believes that in order to flourish, art needs the company of colleagues, the spirit of collaboration, the comfort of continuation, a public forum in which to be evaluated and fiscal support."

Annually, La MaMa prides itself on introducing to audiences at its two East Village venues to artists from around the world. "Cultural pluralism and ethnic diversity have been inherent in the work created at La MaMa," notes Ms. Stewart. "Whatever else you say about us, and plenty has been, you definitely can say we are an international theater company."

To date there have been more than 1,900 productions - and over 1,000 original scores. Resident troupes have traveled the world: Australia, Austria, Brazil, Columbia, Belgium, Croatia, Denmark, England, Finland, France, Greece, Holland, Iran, Italy, Korea, Lebanon, Venezuela, Macedonia, The Netherlands, Scotland, Siberia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, Ukraine and Yugoslavia.

Mama has lectured and directed, written librettos and composed music for shows presented throughout Africa, Asia, Europe and Latin and South America.

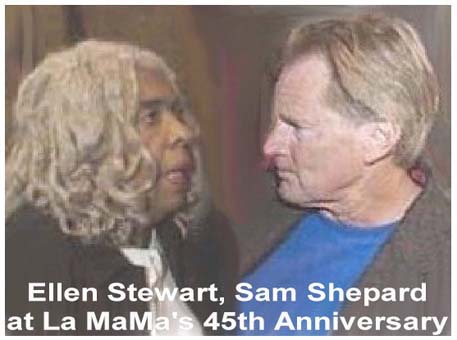

La MaMa has given work to fledging actors, such as Bette Midler, before anyone ever heard of her, and writers such as Harvey Fierstein and Sam Shepard; composers Tom Eyen, Philip Glass and Elizabeth Swados; directors Wilford Leach, Tom O'Horgan and Romanian director Andrei Serban [still active with the company]. The company introduced New York to troupes such as Mabou Mines; and theater from the Eastern bloc, especially with the debut in the company's first decade of Polish ultra avant-garde theater director Jerzy Grotowski.

The company name came about because playwrights, directors, actors, designers and staff in the early years considered Stewart a mother figure. As one put it, "In those days, we were all kids and she was the adult." Actually, in mind, body and spirit, she was probably younger than them. To this day, even in her 80s, she still thinks young and has a sly, devilish spirit. And an incredible memory!

In a rare nod to Off Broadway and beyond, in 1993 Stewart was elected by critics to the Theatre Hall of Fame. She's been honored with dozens of Drama Desk Awards and over 30 Obies. And Ms. Stewart has been given so many honorary and distinguished service awards and doctorates that she has an archive and archivist to keep track of them; and cataloging the early work presented.

La MaMa started ever so simply. It was such a lark that, according to Mama, no one really knew exactly what they were doing. They just had ideas and decided they were going to bring them to fruition. "Never in a million years did I ever think we would accomplish all we've accomplish and become what La MaMa has become," she says. "Our mission was and is to develop, nurture, support, produce and present new and original performance work by artists of all nations and cultures."

In fact, growing up in Chicago, theater never entered Ellen Stewart's mind. She wanted to be a fashion designer. As a young black woman, she knew it wouldn't be easy. "No surprise," she laughs, "it wasn't. At that time Chicago had nothing on the Deep South as far as racism rearing its ugly head."

To escape, she came to what she thought was very cosmopolitan New York City. But there were surprises here, too. "Bernard Gimbel, then president of Gimbel's, hired me as an executive designer for their Sak's Fifth Avenue store, but found resistance from their high-end customers." But stick by her, he did. By the time doors started to open, she had met an interesting circle of friends - some in very high places. And, in a nutshell, she decided one night to put on a show.

La MaMa began as a tiny, second-floor space over a Second Avenue tailor shop. Interestingly, Miss Stewart said she didn't start off looking to be controversial, "but we certainly stirred up quite a bit of controversy."

The first play "to get us some headlines" was O'Horgan's 1964 production of Genet's The Maids " because of his decision to do it with boys." She notes that the show that really put La MaMa "on the map," and in more ways than one, was 1967's Futz by Rochelle Owens and directed by O'Horgan.

The dark, very dark, comedy didn't exactly conform to social norms of the day. Without raising her voice in exclaimation - in fact, very matter-of-factly, Mama recounts the story. "It was about a farmer who's had so many bad experiences with women that he falls in love with Amanda, his pet pig, and marries her. There was also a very attractive, but not too tightly-wrapped hayseed who's a Peeping Tom at Mr. Futz's basement window. While Mr. Futz had, well, darlin', let's just say intercourse with his pig and told her that they'd always be together, the chorus made sexual sounds which was exciting the boy. The town's most beautiful and richest girl - a stunning blonde, has a crush on him.

John Bakos [Cyrus Futz] starred along with Seth Allen, Mari-Claire Charba and Frederick Forrest. Sally Kirkland did narration.

"Now, Tom is a composer and musician," she continues, "He could play every instrument imaginable. So there he is in the wings with various instruments tied and hanging on him - a one-man orchestra. He had made a living singing on the Borscht Best as a counter tenor and he was making these sounds.

"One night, the boy brings the girl to watch Mr. Futz and Miss Pig. He starts using Mr. Futz's rhythm and the more Mr. Futz gets - gets - you know. Yes - very excited, the more the boy gets excited; and, in a very dramatic and graphic scene, he rapes the girl. He's arrested and is sentenced to hang. His mother comes to pay a last visit and they commiserate in a Southern cracker dialect. To suckle him, she exposes a breast and puts it in his mouth. Well. Right. Nothing like this had been done before."

As word spread, lines formed around the block. La MaMa's tiny space couldn't contain the crowds. When asked how long a run the play enjoyed, Miss Stewart laughs, "We don't got runs. We never had runs. Unless you want to count me running. La MaMa's early history is marked by the number of times I was running. Running from the police! Always running! We couldn't stay long!"

Mama also decided to tour the show in England and Europe. "Now, after what happened here, imagine this in very conservative Edinburgh!" Were there protests? "Protests?" she asks. "Oh, yes! The Scottish Daily Mail accused me of shipping filth to their country."

The controversy sold tickets. "They had lines down the block," she states not able to control her excitement or laughter, "and around the block, down and around another block, across the street and down another block. You had to see this scene of local women protesting with placards accusing us of all sorts of things, and audiences wanting us to do five shows a night!" As it played Germany and other cities in Europe, the scene was repeated over and over.

"You wanted to know what put us on the map!" adds Mama. "After that, we were known! So we all were laughing when there was all that fuss over nudity in Tom's Hair. That was nothing!"

Futz! later transferred to what is now the Lucille Lortel and Actor's Playhouse; and was filmed, says Miss Stewart, "with Sally riding buck naked on a pig!"

Bette Midler got her first theatrical break at the original La MaMa on Second Avenue with Tom Eyen in Miss Nefertiti. "She had just arrived from Hawaii," recalls Miss Stewart, "and she was a knockout. Quite voluptuous. Those breasts! She was supposed to be nude from the waist up, but Bette was quite modest in those days. She wouldn't take her hands off her boobs. We would go, 'Bette, psssst. Come on. Go ahead.'"

Harvey Fierstein, whom Mama had the pleasure of introducing at his recent induction into the Theatre Hall of Fame, also started at La MaMa. "We will never forget his debut!" says Stewart. "He came running onstage with his fly unzipped and his cockylove popped out. He ran off stage and I had to get down on my hands and knees to sew the fly shut."

Nudity in La MaMa shows caused "some" problems, but, says Mama, "I never did it; but, back in the day, I was really beautiful and if a role called for me to run naked, I would have. But no more!"

It didn't take long for La MaMa to outgrow Second Avenue. In 1969, it began business on East Fourth between First and Second Avenues in a building that now comprises two theatres and a cabaret.

Stewart discovered the work of Serban and brought him to La MaMa that year. "I was much more political then, and concerned with the state of the Negro or black or whatever we were called and how we were shown culturally. I wanted to do theater where a black could play a role that didn't require a needle in the arm, a jail cell, being a domestic washing dishes or clothes or being in the morgue."

To accomplish this goal Serban, "who didn't know from black and white," and Swados chose Medea, and cast black actress Betty Howard. It was decided to do the play in Greek because "to Andrei and Elizabeth's ear, the way Americans spoke English didn't sound poetic enough." She is cracking up laughing, having a difficult time catching her breath as she described the long process of putting the play in French, German and several other languages. Finally, Andrei, who's half Greek, said, 'Let's try Greek.' I got a tutor to teach the company and it was sounding pretty good. Still, with the music Elizabeth had in mind, they decided to translate further into 'Ancient Greek,' and were finally satisfied the music went with that."

When Howard was cast in a Broadway show, Priscilla Smith stepped in, receiving great acclaim in what became a landmark production for La MaMa, that tour internationally. It was the first of several collaborations between Serban and Swados.

Controversy followed to the new site. Mama got arrested several times. She recalls harrasment from the Fire Department over safety issues at La MaMa, especially during the Koch administration. She claims the former Mayor was out to get her and close La MaMa.

The first show there was Caution: A Love Story, written and directed by the late Tom Eyen with music by the late Bruce Kirle [later a generous scholarship donor at La MaMa]. Eyen went on to become a Broadway director, playwright and lyricist. One of his first Broadway assignments was being brought aboard to direct Paul Jabara's 1973's Rachael Lily Rosenbloom and Don't You Ever Forget It [the musical satire Jabara wrote with Bette Midler in mind to star. She didn't. Jabara, Ellen Greene, Anita Morris and Andre De Shields did], but it never officially opened]. Of course, he will forever be known in theatrical books as the lyricist and book writer of Dreamgirls, with music by Henry Krieger.

Popularity and demand for tickets meant having to find larger space and, in a lottery for East Village buildings owned by the City, Miss Stewart landed a few doors West in what is called The Annex. Grant money from the Ford Foundation paid for the extensive renovations in a building that had once been a TV sound stage and, as legend has it, the last place Judy Garland recorded a song for a movie.

It opened in 1974 with The Trojan Women presented, as had become tradition, in Swados' invented language.

Miss Stewart has had many memorable milestones, from the controversial to the beautiful, such as the first chamber opera, Camila, about two Lesbian vampires, in 1970, which was created by Wilford Leach, the La MaMa's A.D. He went on to become a resident director at the Public and direct The Pirates of Penzance and Rupert Holmes' The Mystery of Edwin Drood, for which he won Tony and Drama Desk Awards.

According to Mama, Leach as designer and director, was quite the ahead-of-his-time theatrical innovator. "He used projected slides and film to enhance the opera. Cast members used mikes onstage. When I tell people this, they call me a liar. They say nothing like that was done then. But it was, and it was done at La MaMa."

When Leach returned to La MaMa in 1981 to revive Camila, the earlier production was recalled. "The Village Voice lead theater critic wrote a page-long article asking how we stoop so low as to claim we had opera, projections and the like in 1970 when it didn't exist anywhere in the world. Needless to say, a big fight broke out between me and the Voice. I went down there with a baseball bat, but I won. I even went so far to forbid entry to their critics. However, they threatened a lawsuit, stating that I couldn't bar anyone."

Along the way, Mama found generous benefactors along the way; and La MaMa's work has benefited from, believe it or not, the usually conservative National Endowment for the Arts. In addition to theater and cabaret, La MaMa's has internships at the high school and college level and a ticket subsidy program open to students, seniors, social orgs and the physically and mentally-challenged allowing attendance at performances at no cost.

In 1986, with the proceeds from a MacArthur Genius Award, Miss Stewart founded La MaMa Umbria, an artists' retreat in Umbria, Italy, where workshops and festivals are held each summer.

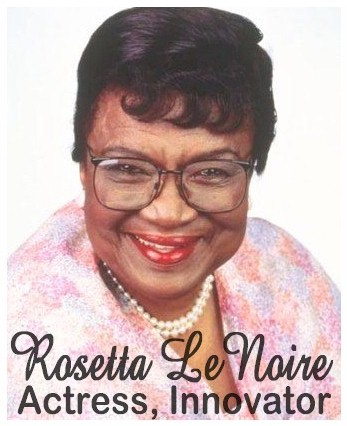

Actress, TV Star and Off Bway Innovator: Rosetta LeNoire

Rosetta LeNoire, "Rosie" to everyone who loved her [and that list was a very, very long one], at 5' 2" was tiny in statue but was quite the dynamo. After years of acting in starring roles and seguing into major and memorable character portrayals, she had a dream to form a theater company that wasn't black or white but a company for everyone.

Ms. LeNoire's family emigrated from the Caribbean island of Dominica. She suffered from rickets and wore leg braces for 13 years.

Rosie's godfather was the legendary dancer, Bill "Bojangles" Robinson. "I began my career as a child performer, Rosetta Olive Burton," she once recalled. "It was an unusual debut. Bill would plant me in the audience and then pluck me out and bring me up onstage. Before you know it, we were singing and dancing!"

Her mother died of pneumonia at age 27 after giving birth to her brother in a Harlem hospital corridor because segregationist policies barred her from having a room.

Acting in Robert Earl Jones' troupe, Rosie had the distinction of baby-sitting James Earl Jones, who became a life-long friend and supporter.

In 1936, Miss LeNoire made her Broadway debut in the limited run of Orson Welles' landmark all-black "voodoo" adaptation of Macbeth, produced by the Negro Theatre Unit of the WPA's Federal Theatre Project and John Houseman. She was back on Broadway in 1939 as Peep-Bo in Mike Todd's all-black Hot Mikado [which starred Robinson as the Mikado].

She made her TV debut in the early 50s on a soap and went on to play countless roles in live TV dramas and specials. She was featured in Philip Yordan's controversial 1959 film Anna Lucasta. In 1966, she played Queenie in Lincoln Center's production of Show Boat.

Growing up in New York, Ms. LeNoire, who died in 2002 at age 91, struggled against racism during her touring years and knew the drill about African-American actors having to stay in their own hotels or rooming houses. She often spoke of those early years when she was perpetually typecast in the role of the maid. "There were so many of them," she once joked, "I lost count."

During enactment of civil rights legislation in the 60s, she had what she called "an epiphany" to change how theater is perceived. In 1968, she founded of Amas [Latin for "you love"] and segued from actress to a pioneering figure in American theater.

Playing a nurse, she joined the cast of Neil Simon's The Sunshine Boys and appeared in the 1975 film adaptation. That year she was seen in Stanley Kramer's ABC-TV adaptation of Guess Who's Coming to Dinner; and on Broadway opposite George Grizzard, Rosemary Harris, Eva Le Gallienne, Sam Levene and Mary Louise Wilson in Ellis Rabb's hit revival of The Royal Family, which was filmed for TV.

Years later, it was on TV that Rosetta LeNoire became a household word playing world-weary, but all-wise "Mother" Winslow, the grandmother, on ABC's hit sitcom Family Matters. The money she made helped finance her dream.

She related that at a job interview in Harlem, she overheard a teacher ask children, "Who do we love?" "Their answer was, 'We love black!' And the teacher asked, 'Who do we hate?' And they replied, 'We hate whitey!' I thought, my God, we worry about our kids getting into alcohol and drugs, but this is worse. I felt it was poisoning their minds, and at a time when they couldn't make decisions for themselves."

When she related the incident to her husband, he encouraged her "to do something about it." That night, "on broken-down typewriter, I started writing letters." Among the letters was one to the New York State Council on the Arts. "I didn't know anyone there, so I wrote to several; and all answered! When I went for the interview, I had my male business manager and two young women, one Jewish and the other, Korean. When I explained what I wanted, I was asked, 'Why don't you want an all-black theater?' I answered, 'My world is not all black. My world is as God created it, all colors, a glorious bouquet.'"

Rosie was informed she'd have a difficult time because so much funding was going to black cultural groups, but decided to take her chances. "I prayed and made Novenas and asked others to pray. A month later, a miracle happened. I received a check for $25,000. And that was how Amas started!"

One of her first big projects was the musical revue Bubbling Brown Sugar in 1973, which later moved to Broadway where it became a huge hit. As things at Amas developed, Rosie was an exponent of diversity through non-traditional casting.

In a production of The Bingo Long All-Stars, about the Negro baseball leagues [which later was the basis for a film co-starring James Earl Jones, Billy Dee Williams and Richard Pryor], Rosie was criticized for casting a young, red-headed white male as one of the Negro players. She was quick to respond, "I was denied roles because of my color. I'll be damned if that will ever happen in my theater! AMAS is not a black theater." She did make a small compromise by asking the actor to wear dark make-up.

In 1989, Rosie was honored by Actor's Equity with the establishment of the Rosetta LeNoire Award, given annually to producers and theatre companies who exemplify her commitment to multicultural production and casting in the theatre. Rosie was the first recipient. Then AE prez Colleen Dewhurst, with whom Rosie worked with in YCTIWY, presented and stated, "This is given in recognition of your outstanding artistic contributions to the universality of the human experience in the American Theatre."

In 1999, President Clinton awarded Miss LeNoire the National Medal of Arts to Rosie along with Aretha Franklin, Steven Spielberg, Garrison Keillor, dancer Maria Tallchief, BAM's Harvey Lichtenstein and George Segal.

With Miss LeNoire co-starring in a hit TV series, Amas needed a full-time A.D. Donna Trinkoff came aboard and, as Rosie entered a long period of illness and on her death, continued the mission and the tradition of multi-cultural casting began by Rosie. Under Trinkoff, the company has become a leading not-for-profit lab for new musicals, including the very recent Wanda's World, Shout!: The Mod Musical, Lone Star Love and Zanna, Don't.

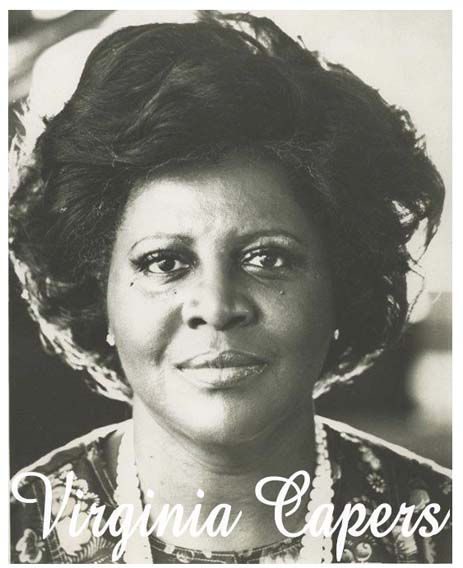

Remembering Virginia Capers

South Carolina-born Virginia Capers studied voice at Julliard, but according to her son Glenn, a photographer, she was expelled when she became pregnant. She ended up as vocalist in a band heard on radio and which toured. She found roles on Broadway in musicals, 1957's Jamaica, which starred Lena Horne, and 1959's Saratoga, set in the 1880s in New Orleans and New York. From the early 60s on, she was cast in ever larger roles in TV dramas.

Glenn Capers said, because she was black, his mother spent a lot of her life being told she should sing the blues. That wasn't her plan. In fact, she diligently fought black stereotypes. "Though Mother often found herself in those roles out of necessity," he said, "she was eventually allowed to become more 'professional,' playing nurses and judges - any role other than the poor, single Mom struggling to make it."

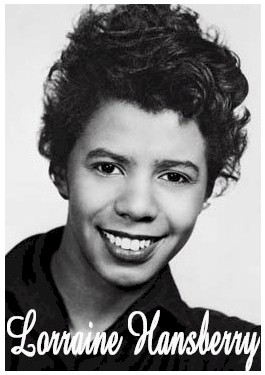

Her her first starring role on Broadway came in 1973 when she won the coveted role of Lena Younger in musical adaptation of A Raisin in the Sun, called Raisin. She opened to great acclaim and was nominated for and won the Tony, the first black woman to win solo.

The landmark for blacks on Broadway was 1950 when the Juanita Hall became the first African-American to win a Tony, for her acclaimed featured role as Bloody Mary in R&H's original Tony-winning South Pacific. Fifteen years later, Leslie Uggams won in the Actress, Musical, category for her performance in the Tony-winning Best Musical, Hallelujah, Baby!. But it was a tie, with Patricia Routledge - yes, later to become TV's Hyacinth Bucket and Hetty Wainthropp - in the short-lived Darling of the Day.

"Raisin was her true love," recalls Glenn. "No one expected her not to win the Tony [that year's Tony category had Miss Capers up against only Carol Channing in Lorelei and Michele Lee in Seesaw]. That night, I watched in silence as she got ready. On the way to the theatre, I slipped her a note saying this was going to be her night, as other blacks had had theirs for the trails they blazed. I felt their spirits were guiding her.

"When the envelope was opened," he continues, "and from the silence her name sprang out, Mom lifted out of her seat as if on wings. She started toward the stage, turned back and hugged me. 'It's mine!,' she whispered. Afterward, everyone gathered around wanting to touch her and share her moment of joy. It was like a revival meeting! Her winning was Mom saying to all those with dreams and aspirations, 'Yes, you can do it!'"

In the press room, according to Glenn, the reporter from The New York Times rushed passed her to interview Channing and Lee. "He didn't seem to care that history was made that night. But Mom stomped her foot down and said, 'Excuse me! I am the Tony Award winner. You interview me!' He did, and it appeared the next day.

Miss Capers went on to play Lena Younger in Hansberry's play, but didn't appear on Broadway again. For her role in an episode of TV's Mannix, she earned her a 1973 Emmy nomination. In the 70s into the late 89s, she was featured in such major films as The Great White Hope, Lady Sings the Blues and Ferris Bueller's Day Off. She founded and acted with the Lafayette Players, a Los Angeles repertory group comprised mostly of black actors.

Virginia Capers died, after a long illness and many complications following heart problems, cancer and hip replacements, in L.A. in 2004. She was 78.

"Mom's last wish," says Glenn, "was to make sure all races and nationalities could be identified for their accomplishment in theater." He explains there's no record of her attending Julliard, where she became close friends with Mississippi-born Leontyne Price, who went on to international fame in opera.

Actors Union Has Fought Inequality

Actors' Equity was one of the first unions to stand up against "Jm Crow." In 1944, the union created a committee to assist minority actors turned away on the road from segregated hotels. Jose Ferrer, who co-starred with Paul Robeson in Othello on Broadway, was outraged by segregation and announced he'd never perform in front of a segregated audience.

Two years later, Ingrid Bergman and the cast of Joan of Lorraine, complained to AE about audience segregation at the legit theatres in Washington. The union took a strong stance stating that unless the situation was remedied, they would forbid members to play there. The policy was reversed, a milestone in the early days of the civil rights movement.

Equity continued to monitor segregation and announced in 1952 that its members would not perform in South African theatres while apartheid existed. AE sponsored showcases for casting directors and producers to push non-traditional casting.

The union also used its clout to defeat racism through collective bargaining. In 1961, AD and the League of American Theaters and Producers [now the Broadway League] agreed that no member of Equity would be required to perform where discrimination was practiced and the Ethnic Minorities Committee was formed.

In 1964, Fredrick O'Neal, one of the founders of the Negro Actors Guild, became the first African-American president of Actors' Equity. By 1980, all Equity contracts contained clauses encouraging the casting of actors of color, actors with disabilities, women and seniors.

Bert Williams: Forgotten Black Star

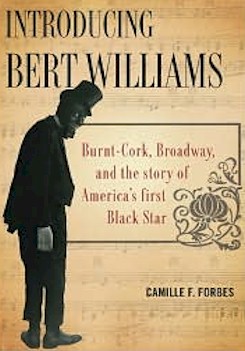

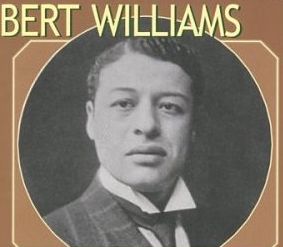

Camille Forbes introduces us to a long ago world of intense racism in America, but a world where the color barrier was broken on Broadway and a medicine show performer became a star in Introducing Bert Williams [Basic/Civitas Books, 404 pages; Photos, index, extensive bibliography; SRP $27.50}

Born in the West Indies, his dream from childhood was to become a song and dance man. From Wild West touring troupes, Williams landed on the Great White Way, where he not only became one of the first blacks to break through but also changed the face of the American stage. Forbes argues that every black performer owes something to Williams, who rose through vaudeville in New York to become a Broadway composer/lyricist, with his first show produced in 1889. He debuted as a performer the following year.

In 1903, he was featured in the first all-black cast on Broadway in the musical farce In Dahomey. The score, not by Williams, consisted of the no-longer politically correct "When Sousa Comes to Coontown." Three years later, he composed and starred in the musical comedy Abyssinia.

In 1910, Williams became the first black star of the fabled revues of beautiful girls, the fabled Ziegfeld Follies. The impresario knew he was making a bold move, and he was severely criticized for integrating the company by many of his investors and audience members. Williams, singing his signature tune "Nobody" and doing rubish comedy, played on the same stage as Fanny Brice and W.C. Fields [even if his salary wasn't comiserate with theirs]. He starred in seven more editions before his death in 1922 at 47.

Inspite of his triumphs, Williams was often viewed by the black community with more critical suspicion than admiration because he performed in blackface and the fact that he didn't use his stardom as political or civil rights activism.

His was a remarkable performer, but Forbes, a historian, critic, and performer who holds Ph. Ds in history and American civilization from Harvard and who's an assistant Literature professor at the University of California, San Diego, but also offers a realistic glance at his inner turmoil.

Williams was to see fame again on Broadway when his songs were used in Bubbling Brown Sugar and the 1980 revue Tintypes.