[Broadway Ad Network]

[Broadway Ad Network]

TICKET / INFO

- StudentRush

- New York Show Tickets

- Givenik.com

- Telecharge.com

- Ticketmaster.com

- Group Sales Box Office

- Frugal TheaterGoer

- Broadway for Broke People

- Playbill's Rush/Lottery/SR

- Seating Charts

COMMUNITY

NEWS

- Back Stage

- Bloomberg

- Broadway.com

- BroadwayWorld

- Entertainment Weekly

- NYTheatre.com

- New York Magazine

- The New York Daily News

- The New York Post

- The New York Times

- The New Yorker

- Newsday

- NiteLife Exchange

- Playbill

- Show Business Weekly

- The Star-Ledger

- Talkin'Broadway

- TheaterMania.com

- Time Out New York

- American Theatre Magazine

- Theatre Development Fund (TDF)

- Best of Off-Broadway

- The Village Voice

- Variety

- The Wall Street Journal

- Journal News

REVIEWS

- The New York Times

- Variety

- New York Post

- NY1

- Aisle Say

- CurtainUp

- DC Theatre Scene

- Show Showdown

- Stage and Cinema

- StageGrade

- Talk Entertainment

- TotalTheater.com

- Off-Off Broadway Review

- TheaterOnline.com

- TheaterScene.net

- TheaterNewsOnline.com

WEST END

- The Stage

- 1st 4 London Theatre Tickets

- Book Your Theatre Tickets

- Compare Theatre Tickets.co.uk

- Theatre.com

- Whatsonstage.com [UK]

- ATW - London

- Musical Stages [UK]

- Albemarle of London

- Londontheatre.co.uk

- Google News

- Show Pairs

- ILoveTheatre.com

- The Official London Theatre Guide

- UK Tickets

BOSTON

CHICAGO

LA/SF

COLUMNS

- Peter Bart

- Andrew Cohen

- Ken Davenport

- Tim Dunleavy

- Peter Filichia

- Andrew Gans

- Ernio Hernandez

- Harry Haun

- Chad Jones

- Chris Jones

- James Marino

- Joel Markowitz

- Matthew Murray

- Michael Musto

- Ellis Nassour

- Tom Nondorf

- Richard Ouzounian

- Michael Portantiere

- Rex Reed

- Michael Riedel

- Frank Rizzo

- Richard Seff

- Frank Scheck

- Mark Shenton

- John Simon

- Robert Simonson

- Steve on Broadway (SOB)

- Steven Suskin

- Terry Teachout

- Theater Corps

- Elisabeth Vincentelli

- Hedy Weiss

- Matt Windman

- Linda Winer

- Matt Wolf

PODCAST

RADIO

TV

- Theater Talk

- BlueGobo.com

- Classic Arts Showcase

- American Theatre Wing Seminars

- Women in Theatre

- NY1

- WCBS [2]

- WNBC [4]

- FOX [5]

- WABC [7]

- WWOR [9]

- WPIX [11]

- Channel 13

- Hulu

- YouTube

AWARDS

- Tony Central

- Oscar Central

- Tony Awards

- Drama Desk Awards

- The Drama League Awards

- Lortel Awards

- Academy Awards

- Emmy Awards

- Grammy Awards

- GoldDerby

DATABASE

- Internet Broadway Database

- Internet Off-Broadway Database

- Internet Movie Database

- Internet Theatre Database

- Musical Cast Album Database

- [CastAlbums.org]

- Show Music on Record Database (LOC)

- CurtainUp Master Index of Reviews

- Musical Heaven

- StageSpecs.org

ROAD HOUSES

- Gammage [AZ]

- Golden Gate [CA]

- Curran [CA]

- Orpheum [CA]

- Community Center [CA]

- Civic [CA]

- Ahmanson [CA]

- Pantages [CA]

- Temple Hoyne Buell [CO]

- Palace [CT]

- Rich Forum [CT]

- Shubert [CT]

- Bushnell [CT]

- Chevrolet [CT]

- Broward Center [FL]

- Jackie Gleason [FL]

- Fox [GA]

- Civic Center [IA]

- Cadillac Palace [IL]

- Ford Center/Oriental [IL]

- The Bank of America Theatre [IL]

- Auditorium Theatre of Roosevelt University [IL]

- Kentucky Center [KY]

- France-Merrick [MD]

- Colonial [MA]

- Wilbur [MA]

- Charles [MA]

- Wang [MA]

- Wharton Center [MI]

- Whiting [MI]

- Fisher [MI]

- Masonic Temple [MI]

- Orpheum, State, and Pantages [MN]

- Fabulous Fox [MO]

- New Jersey PAC [NJ]

- Auditorium Center [NY]

- Proctors [NY]

- Shea's PAC [NY]

- BTI Center [NC]

- Blumenthal PAC [NC]

- Schuster PAC [OH]

- Playhouse Square [OH]

- Aronoff Center [OH]

- Ohio [OH]

- Victoria Theatre [OH]

- Birmingham Jefferson [OH]

- Merriam Theater [PA]

- Academy of Music [PA]

- Benedum Center [PA]

- Providence PAC [RI]

- Orpheum [TN]

- Hobby Center [TX]

- Music Hall [TX]

- Bass Hall [TX]

- Paramount [WA]

- Fox Cities PAC [WI]

- Marcus Center [WI]

- Weidner Center [WI]

FESTIVALS

- The New York International Fringe Festival

- The American Living Room Festival

- Summer Play Festival

- The New York Musical Theatre Festival

- Adirondack Theatre Festival

- NAMT: Festival of New Musicals

SPECIAL

- BC/EFA: Broadway Cares / Equity Fights AIDS

- The Actors' Fund

- Stage Directors and Choreographers Foundation

EDUCATION

- Google Shakespeare

- Actor Tips

- AACT

- ArtSearch

- Broadway Classroom

- Broadway Educational Alliance

- Camp Broadway

- Great Groups - New York Actors

- Theatre Communications Group (TCG)

- Theatre Development Fund (TDF)

- Off-Broadway Theater Information Center

UNIONS/TRADE

- AEA

- SAG

- AFTRA

- AGMA

- The League

- APAP

- Local 1

- ATPAM

- IATSE

- AFM

- AFM - Local 802

- Treasurers & Ticket Sellers Union

- DGA

- Dramatists Guild

- USA 829

- WGA, East

- WGA, West

- SSD&C

- AFL-CIO

- League of Professional Theatre Women

NYC NON-PROFITS

- Cherry Lane Theatre

- City Center

- Drama Dept.

- Ensemble Studio Theater

- Jean Cocteau Rep.

- Lark

- Lincoln Center Theater

- Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts

- Lucille Lortel Foundation

- Manhattan Theatre Club

- MCC

- Mint

- Pearl Theatre Company

- Public Theater

- Roundabout

- Second Stage

- Signature

- The Vineyard Theatre

- The York Theatre Company

REGIONAL

- Actors Theatre

- Alabama Shakespeare Festival

- Alley Theatre

- ACT

- American Musical Theatre in San Jose

- American Repertory

- Arena Stage

- Barrington Stage Company

- Bay Street Theatre

- Berkeley Rep

- Casa Manana

- Chicago Shakespeare Theater

- Cincinnati Playhouse

- CTC

- Dallas Summer Musicals

- Dallas Theater Center

- Denver Center

- George Street

- Goodman

- Guthrie

- Goodspeed

- Hartford Stage

- Hudson Stage Company

- Theatre de la Jeune Lune

- Kennedy Center

- La Jolla

- Long Wharf

- Lyric Stage

- Mark Taper Forum

- McCarter

- New Jersey Rep

- North Shore

- Old Globe

- Ordway

- Oregon Shakespeare

- Paper Mill

- Prince Music Theater

- The Rep (St. Louis)

- Sacramento Music Circus

- San Francisco Mime Troupe

- Seattle Rep

- Shakespeare Theatre Co. (DC)

- The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey

- South Coast Rep

- Steppenwolf

- Theater of the Stars (GA)

- Theater J (DC)

- Theater Under the Stars (TX)

- Trinity Rep

- Two River Theater Company

- Utah

- Victory Gardens

- Westport

- Williamstown

- Yale Rep

KEWL

THE GREATEST SHOW ON EARTH - WITH A BROADWAY PEDIGREE

by Ellis Nassour

-

Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus "spec" production number staged

by Broadway's Philip Wm. McKinley and Tony Stevens.

Do you look forward to family reunions? Hummmm. You have your pros and cons. Each Spring, New York City is host to a family reunion when the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus train arrives and pitches its "Big Top" at Madison Square Garden. Through April 10, like at most family reunions, there'll be beauty, brawn and "beasts" - and more than a bit of zany insanity.RBBB is as heavy with family tradition as it is with hyperbole in its advertising. The circus family is comprised of artists, most of whom are billed as doing the most incredibly daring feats, and dancers [including stunning showgirls in dazzling costumes] from every corner of the world.

Like those of some relatives at family reunions, the antics of the more daring artists make the hairs on the back of your neck stand up. And what's a reunion without a clown. Ringling has more than its share and they will have you, intentionally, screaming with delight. Okay! Talk about hyperbole - they'll have you ROTFWL.

"Tempting fate daily isn't merely a tag line this season," says RBBB impresario Kenneth Feld, the financial genius behind Ringling Bros. and its spin-offs [Disney ice shows], quite seriously, "it's a mandate. Each performer goes one step beyond in putting themselves on the line. The tried-and-true circus magic is present and, right before your eyes, we sweep you to places you've never imagined. You might define it as an extreme makeover! We've taken the ëcircus' and turned it on its head."

To keep the show as fresh as possible [no easy task], Feld and and associate producer, daughter Nicole, constantly search here and abroad for the for the best and out-of-the-ordinary acts. "My aim is to surprise and astound," says Mr. Feld. "I want audiences to sit back and roar, ëThis is The Greatest Show On Earth'!"

That takes lots of money, but Feld has built an impressive family entertainment empire. Sometimes, others may do certain elements better, but no one does them bigger.

Director Philip Wm. Kinley, right, choreographer Tony Stevens,

left foreground, with circus artists; McKinley rehearses in the arena.

"Welcome to the world of the circus!

Welcome to a place beyond your dreams!

Where everything around you will shock you

And astound you

And nothing's quite exactly what it seems!Ö"

ó Lyrics by Glenn Slater, from "Welcome to the World of the Circus"

With increased competition from video games, blockbuster movies, TV, DVD and the VCR, the "makeover" has truly been extreme. Ringling's no longer your mother's circus; however, Feld brought in some theater professionals to restore some of the long-missing traditional luster.The person responsible for fine-tuning RBBB and giving it a new look is director/ choreographer Philip Wm. McKinley, who - after paying his dues directing and choreographing Off Broadway, regionally [the musical adaptation of James Michener's Sayonara and abroad [the Kopit/Yeston Phantom] - last season helmed The Boy from Oz, starring Down Under megastar Hugh Jackman. He's given RBBB a very distinctive theatrical concept with a basic sense of story line.

To check McKinley out, Feld contacted one of his employers, Frank Young, the respected director of Houston's Theatre Under the Stars and also a presenter of shows in Minneapolis and Seattle. He wanted to know if the director had experience with large-scale production numbers. Young, because of McKinley's work in Vegas, Houston and at such large venues as the St. Louis MUNY and Kansas City Starlight Theatre, dubbed him "the Great Ziegfeld of our generation."

"Is he a team player?" Feld also inquired of Young. "I told him, ëYes, but you'll be working on his team.'"

But, really, says McKinley, "it's our team. Kenneth is very creative and knows the circus. He's very hands-on and not up in some glass tower. If I get stuck, he's the person I turn to. He knows how to make it right. The reason we get along is because we're totally honest with each other. And our bottom line is the same: achieving the best show possible."

With an annual budget in excess of $12-million, McKinley says it's amazing what you can do: sets, props, lighting, music [including an original score and songs] and choreography.

Much of the credit in the latter department goes to veteran Broadway choreographer/director Tony Stevens, a huge circus fan and a veteran of Broadway [assistant to Bob Fosse on 1975's Chicago] Off Broadway, regional theater, TV specials and star club acts [including being one of Chita's boys and now a close associate].

In addition to the dance ensemble of 16 women, the artists are contractually required to take part either in dance numbers or such musical staging as riding the elephants. "That's the tough part," laughs Stevens. "Sometimes, they wish they had read the fine print in their contracts. The excuses they use to get out of the numbers are amazing - everything from they've got to brush the horses or bathe the elephants. Eventually, they comply."

One of Stevens' talents, says McKinley, is that he's quite accomplished at teaching people who say they can't dance to dance. "Age and inexperience isn't a factor," explains Stevens. "It's about feeling comfortable and having fun. No one has two left feet. We have a right and a left foot, and the trick is teaching the difference. I've taught everyone from Robert Redford [in the film The Great Gatsby] to the hunks that make up the teterboard troupes, to dance.

"Some of the acrobats are quite coordinated," he continues, "but terribly unmusical. You teach them one by one, with a goal of getting get them all to the same place at the same time. The biggest fear for most of the men is that they'll look foolish. If you get them over that, you've won."

Stage musicals are collaboration and, notes director McKinley, "so is the circus. Maybe, more so. What makes working with Tony such as joy is that we have a great relationship built from working on about a dozen projects. We know what each other's thinking before we're thinking it!"

McKinley explained that his theatrical experiences here and abroad have been invaluable. "Since I've worked with various nationalities, I'm patient and not frustrated when I have to depend on a translator to give directions. Also, it didn't hurt that I had a Vegas background."

But, he has been very careful not to over-theatricalize. "The key is to theatricalize the acts without getting in the way of the acts. If you go in for heavy costuming, lights and music, all of a sudden the act tends to disappear. I try to focus on the personality of the performer as opposed to the personality of the show. It's important to have a clean palate that allows the performer to reach the audience."

He's well aware of his toughest critics: "They're the kids! They're like elephants. They never forget. The ultimate goal for me is making sure Ringling Bros. maintains its standard as an American icon. Every time I watch the show, I observe them. If they like what we're doing, I know we've done a good job."McKinley's quick to praise the younger Feld as "a quick learner. She's been a great asset in that she's very hands-on in every department, but especially when it comes to developing a look for the performers. She's at the design meetings and has influence on everything that happens."

In the 40s and 50s, John Murray Anderson, one of Broadway's most talent and respected director/choreographers was the mastermind of Ringling's tented shows. He put in theatrical routines and production numbers with colorfully-costumed showgirls dancing in the sawdust and twirling on ropes high above the tambark.

There's been a night and day evolution from P.T. Barnum's 1871 traveling museum and menagerie. In fact, old P.T. probably wouldn't even recognize what he originally conceived. But you can bet he'd love the newfangled razzmatazz and razzle-dazzle.

As a theater veteran, he wanted to create an arc for the show. "It took a while to figure out how to do that," admits McKinley. One of the first goals was to tighten the show to keep it running "at lightning speed. That was quite an adjustment."

To achieve a more uniformed look, instead of artists haphazardly wearing just any costume, McKinley decided to specially costume them with original designs by Eduardo Sicangco. Costumes and hats [and even such exotic items as the elephant show blankets] are executed by veteran Broadway suppliers Parsons-Meares, Barbara Matera Ltd., Hagenbeck-Wallace and Florida's Costume World.

With circus, like theater, McKinley says, "audiences go through the gamut of emotions. And we have so many real emotions the circus, you don't have to invent them." With that ideal in mind, he's eliminated certain tricks of the trade performers, especially those who perform high up, did to heighten the emotional experience. "Now, if, God forbid, someone falls, it's an accident. Nothing's faked. It's for real."

Change was inevitable, states Feld. That applied to the music also. Gone are the old, brassy march arrangements. "The traditional music didn't fit the changing pace of the acts," he explained, "or reflect what the performers, who've gotten younger and young, wanted. They're from a different generation and want music that excites them and drives the audience. We're like today's music industry, anything goes as long as it works and helps drive the show."

Unfortunately, quite often during the show, especially for any tried and true [i.e., "older"] fans of the circus, some of the traditional elements are missed. The circus has become more of a MTV daredevil production.One tuneful tradition remains: the singing ringmaster. In 1953, operetta star and symphony vocalist Harold Ronk, now in his mid-80s, "wanted a change of pace and to get out of New York for a while." He auditioned for Anderson, who took one look at his credits and his idea bulb lit. Voila! the singing ringmaster was born.

Says Feld, "The ringmaster is a crucial component in our show, because he's the person who makes the audience feel welcome."

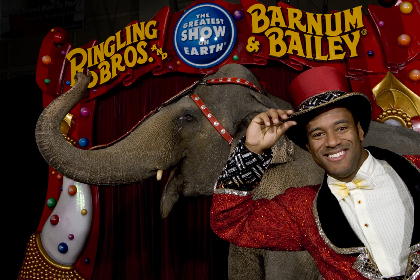

Singing ringmaster Tyron McFarlan and friend.

Wearing the spangled black topcoat, red vest, top hat, extolling "May all your days be circus days!" and singing the original songs in RBBB's Red Unit, is Tyron McFarlan, who graduated with a law degree, but drifted into musical theater [he also a former captain in the Army Naitonal Guard]."When a ringmaster is good," claims Feld, "audiences think he owns the show. Ty is young but projects authority way beyond his years. He's got a superb voice and brings a whole new dynamic to our show."

Though this year's edition has lots of color and glitter, it doesn't quite live up to previous editions or the RBBB subtitle. There is an especially weak addition to the show that involves the ringmaster and clowns taking questions from audience members re: various aspects of the production. I call it Circus 101. Sadly, it adds nothing but a distraction from the performances.Michael Starobin and Glenn Slater, from the world of theater and pop, have contributed an original score and song score.

Starobin is a veteran orchestrator, music director and composer. He orchestrated the Lincoln Center Theater productions of Hello Again and My Favorite Year and contributed to such others Broadway musicals as Sunday in the Park with George, for which he won a Drama Desk Award), the 1992 Guys and Dolls revival directed by Jerry Zaks, the original Assassins and Once on This Island. He orchestrated Disney's animated musical, The Hunchback of Notre Dame, and will be orchestrating the stage version.

"Great shows are music driven," says Feld, who has also co-produced Broadway musicals [including Barnum] and shows. "Music gives the circus its non-stop energy and Michael and Glenn's music affects not only the audience, but also the performers."

According to Ringling Music Director David Killinger, "There's no trace of grand circus fanfares or excerpts from symphonic suites and opera. There is, however, a wonderful variety of music - everything from urban/street rhythms and rock 'n roll to rhythm and blues and Broadway.

This new edition of RBBB, says McKinley, is an orchestrator's field day "because to keep the show moving, moving, moving, the music is faster. The faster the music, the more measures you have. Our score this year has twice as many measures as any show before."

McKinley and Killinger agree that you never want to overpower the audiences with too much. "You don't have to," says McKinley, "because the acts are real. In a high wire display, if you play the theme from, say, Mission Impossible, it will remind the audience of the movie or TV show. We feel our music should be influential without knocking you over the head. We want audiences focused on the act, so the ideal music is the type that supports the act rather than defining it."

The most remarkable thing about the circus for Stevens is the talent. "Our artists dedicate their lives to that five minutes they're in the spotlight," he explains, "often risking their lives four times a day for the sake of entertainment. And, believe me, as we have seen several times in recent years, what they do is not without risk."

If you thought the biggest divas in New York are at our opera houses or starring on Broadway, think again. You have yet to meet the 10 Asian elephants Sacha Houcke, sixth-generation animal trainer, puts through some intricate paces.Talk about risk. Maybe you'll wonder what's racing through the mind of those six showgirls who allow 9,000-pound Asia to do a "walk-over" them. As Dan Rather would say, "Courage."

If you're nice - and aren't all circus fans? - Houcke will bring out his zebras; horses, camels, llamas, zebras and Gandhi the zebu. He controls them all solely by voice commands. Wouldn't it be wonderful if we could do that at family reunions?

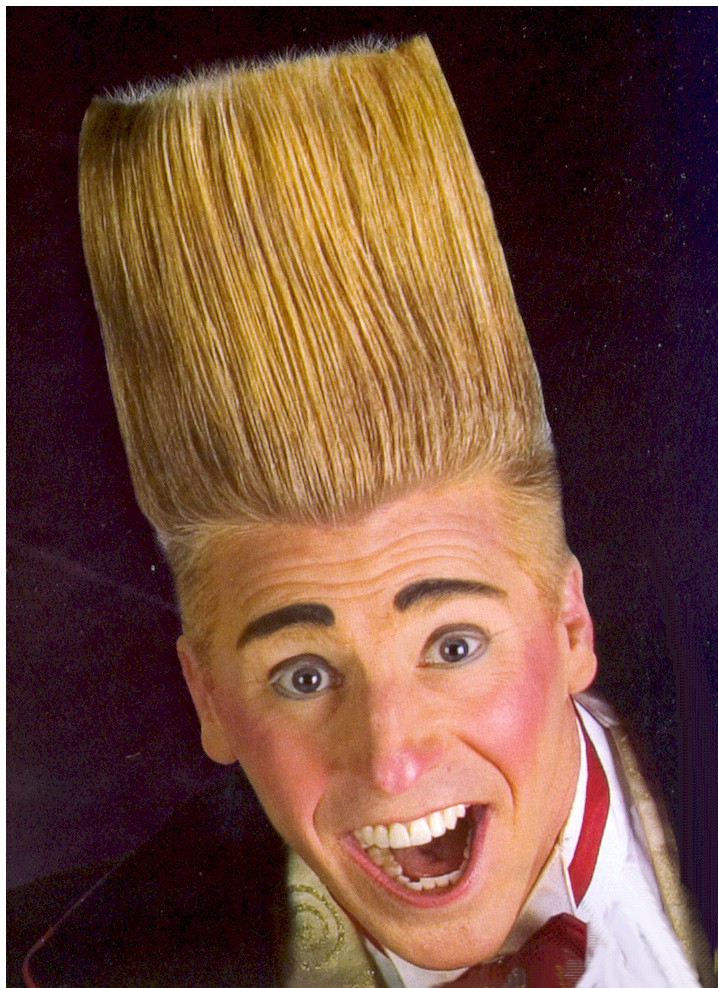

If you're in awe of Manhattan's soaring towers, Bello, the irrepressible daredevil clown with the skyscraper hair, is a seventh-generation member of a Swiss circus dynasty [at age six, he made his Broadway debut as Michael Darling in a revival of Peter Pan]. Named America's Best Clown by Time Magazine, he'll have you on the edge of your seat with his routines, which he definitely advises not to try at home. A couple even he shouldn't have tried, because more than once he's been seriously injured.Instead of a Jacques Brelesque carousel that goes round and round, RBBB has Juan Paulo Rodriguez on the gigantic dual-wheel "Vortex of Vertigo" - walking the walk, running and defying gravity. Bello, who can never resist getting into an act, then struts the wheel.

You thought a chandelier crashing to the stage in a certain musical was exciting? Ringling has two acts that will instill just as much anxiety: youngster brothers Alberto and Mauricio Aguilar on the high wire; and the Windy City Acrobats, who fly through the air with astounding speed and triple sommersaults - maybe even an attempt at a quad by Valentina.

Taba shows his Siberian charges his pearly whites; Bello, the daredevil clown with the skyscraper do [yes, it's real...he uses lotsa gel].We've all seen our share of brawny beasts at reunions and the scene at RBBB is not so different. It just has a bit of a twist: Seventh-generation Chilean animal trainer Taba, whom McKinley says is "loaded with personality." He's also quite the lively acrobat and seemingly fearless, cavorting quite intimately [often kissing a favorite and right in their faces] with a cageful of eight to 10 "ferocious, man-eating" Siberian tigers. Then, in the ultimate spirit of family togetherness, there is husband and wife Brian and Tina Miser being shot through the air with the greatest of ease - from a canon! If only we could do this at some reunions!One of China's esteemed treasures, the massive Inner Mongolia Acrobatic Troupe, will astound you with their agility and feats hoop diving and, in Act Two, their show-stopping pole vaulting.McKinley believes RBBB is an American treasure. "What I've attempted to do is take it back to its origins and salute the tradition that's the pride of the circus. A half-century ago, George Balanchine and Stravinksy orchestrated the choreography and music for Ringling's ëElephant Ballet,' which featured thirty elephants. Now, we not only have the elephants, but also another one hundred and eighty animals."

Taba shows his Siberian charges his pearly whites; Bello, the daredevil clown with the skyscraper do [yes, it's real...he uses lotsa gel].We've all seen our share of brawny beasts at reunions and the scene at RBBB is not so different. It just has a bit of a twist: Seventh-generation Chilean animal trainer Taba, whom McKinley says is "loaded with personality." He's also quite the lively acrobat and seemingly fearless, cavorting quite intimately [often kissing a favorite and right in their faces] with a cageful of eight to 10 "ferocious, man-eating" Siberian tigers. Then, in the ultimate spirit of family togetherness, there is husband and wife Brian and Tina Miser being shot through the air with the greatest of ease - from a canon! If only we could do this at some reunions!One of China's esteemed treasures, the massive Inner Mongolia Acrobatic Troupe, will astound you with their agility and feats hoop diving and, in Act Two, their show-stopping pole vaulting.McKinley believes RBBB is an American treasure. "What I've attempted to do is take it back to its origins and salute the tradition that's the pride of the circus. A half-century ago, George Balanchine and Stravinksy orchestrated the choreography and music for Ringling's ëElephant Ballet,' which featured thirty elephants. Now, we not only have the elephants, but also another one hundred and eighty animals."Cirque Du Soleil reinvented the way upscale, urban audiences view "circus." But, as some argue, while the Felliniesque costumes, unique artists and avant-garde music are great, can there really be a "circus" without animals?

McKinley answers with a resounding, "No!" He states that an intergral part of RBBB is the animals. It's what I've loved most about the circus. If you don't agree with it having animals, then you shouldn't come. You have that choice."

Has the intimacy of such attractions as Cirque De Soleil and the Big Apple Circus influenced Ringling thinking? "Daniel Gauthier, president of Cirque Du Soleil, said they were not a circus," McKinley replies. "I agree, because if you don't have animals you really aren't a circus. Cirque Du Soleil is really a theatricalization of the circus. It's a real theater show and very entertaining. There's a market for that. They are very successful. The Big Apple Circus is wonderful. For a high-end show, it has a large following."He says that Ringling Bros. is and will always be three rings. But, in an attempt to bring the audiences closer, McKinley has initiated some things, such as mike'ing the performers so you can hear them working the act. You hear trainers calling the tigers, elephants and horses, maybe even that zebu, by name and giving commands.

Children of all ages dream of running away to the circus. RBBB helps fulfill that dream with a Circus Celebrity ticket! At $154.50 per ducat, it's a bit pricey, but 64 of you can get pulled from premium seats by friendly clowns and right into center ring to watch Bello and a "spec" up close and personal; then board a train and become part of a glitzy production number. Wave to the audience! Smile for the camera! Is it worth it? You have to decide.

Tickets, the majority modestly priced [but whatever you save, the prices at the concession stands will erase it -- I'm not talking circus popcorn at $6 a box or those spinning lights and swords that light up or even stuffed animal toys, but just plain Cokes, which you can't get during the circus unless you want it in a souvenir cup!], are available at the Garden or through Ticketmaster, (212) 307-7171.______________________________________________

["Here they come, the pride of the circus.

Here they come, our animal stars;

Every beast is a true artiste.

With a talent or two, each a creature of genius,

Almost as smart as youÖ"

ó Lyrics by Glenn Slater, from "The Pride of the Circus"

Note: There is much controversy annually from PETA about circus abuse of animals. Several incidents have been documented and circuses fined (See circuses.com). PETA cites RBBB for alleged abuses and also defeating legislation to prevent abuse. However, director Philip Wm. McKinley, interviewed for this article, states: "Animals are Ringling Bros.' crown jewels, heritage and signature. We are about animals. It was hard not to hear the animal rights people, but I haven't seen anything to be apologizing for. Ringling takes great care of its animals. We're constantly monitored by the Department of Agriculture, who drop in totally unexpected. We're incredibly careful with the animals because we realize it's our responsibility." No one can document animal training methods, but from my observations behind-the-scenes, the animals appear to be well-cared for. There are times offstage when elephants are restrained by chains around their feet and tigers are kept in cages, but there are also times when they roam freely in an "electrified" corral.]

--------Ellis Nassour is an international media journalist, and author of Honky Tonk Angel: The Intimate Story of Patsy Cline, which he has adapted into a musical for the stage. Visit www.patsyclinehta.com.

He can be reached at [email protected]

Why are you looking all the way down here?

For more articles by Ellis Nassour, click the links below!

Previous: JODI LONG OF McREELE: SHE'S DONE IT ALL, BUT IT HASN'T GOTTEN EASIER

Next: LESLIE UGGAMS AND JAMES EARL JONES, TOGETHER FOR THE FIRST TIME, ON GOLDEN POND

Or go to the Archives

[Broadway Ad Network]

[Broadway Ad Network]

If you would like to contact us, you can email us at feedback@

broadwaystars.com

[Broadway Ad Network]

[Broadway Ad Network]

- July 15: Harry Connick, Jr. in Concert on Broadway - Neil Simon

- Sept. 28: Brief Encounter - Studio 54

- Sept. 30: The Pitmen Painters - Samuel J. Friedman Theatre

- Oct. 3: Mrs. Warren's Profession - American Airlines Theatre

- Oct. 7: Time Stands Still - Cort Theatre

- Oct. 12: A Life In The Theatre - Schoenfeld Theatre

- Oct. 13: Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson - Bernard Jacobs Theatre

- Oct. 14: La Bete - The Music Box Theatre

- Oct. 21: Lombardi - Circle In The Square

- Oct. 25: Driving Miss Daisy - John Golden Theatre

- Oct. 26: Rain - A Tribute To The Beatles On Broadway - Neil Simon Theatre

- Oct. 31: The Scottsboro Boys - Lyceum Theatre

- Nov. 4: Women On The Verge Of A Nervous Breakdown - Belasco Theatre

- Nov. 9: Colin Quinn Long Story Short - Helen Hayes Theatre

- Nov. 11: The Pee-Wee Herman Show - Stephen Sondheim Theatre

- Nov. 13: The Merchant of Venice - The Broadhurst Theatre

- Nov. 14: Elf - Al Hirschfeld Theatre

- Nov. 18: A Free Man Of Color - Vivian Beaumont Theater

- Nov. 21: Elling - Ethel Barrymore Theatre

- Dec. 9: Donny & Marie: A Broadway Christmas - Marquis Theater

- Jan. 13: The Importance of Being Earnest - American Airlines Theatre

- Mar. 3: Good People - Samuel J. Friedman Theatre

- Mar. 6: That Championship Season - Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre

- Mar. 11: Kathy Griffin Wants a Tony - Belasco

- Mar. 17: Arcadia - Barrymore Theatre

- Mar. 20: Priscilla Queen Of The Desert The Musical - The Palace Theatre

- Mar. 22: Ghetto Klown - Lyceum Theatre

- Mar. 24: The Book Of Mormon - Eugene O'Neill Theatre

- Mar. 27: How To Succeed In Business Without Really Trying - Al Hirschfeld Theatre

- Mar. 31: Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo - Richard Rodgers Theatre

- Apr. 7: Anything Goes - Stephen Sondheim Theatre

- Apr. 10: Catch Me If You Can - The Neil Simon Theatre

- Apr. 11: The Motherf**ker with the Hat - Gerald Schoenfeld Theatre

- Apr. 14: War Horse - Vivian Beaumont Theater

- Apr. 17: Wonderland: A New Alice. A New Musical Adventure. - Marquis Theatre

- Apr. 19: High - Booth Theatre

- Apr. 20: Sister Act - The Broadway Theatre

- Apr. 21: Jerusalem - Music Box

- Apr. 24: Born Yesterday - Cort Theatre

- Apr. 25: The House of Blue Leaves - Walter Kerr Theatre

- Apr. 26: Fat Pig - Belasco Theatre

- Apr. 27: Baby It's You! - Broadhurst Theatre

- Apr. 27: The Normal Heart - Golden Theater

- Apr. 28: The People in the Picture - Studio 54

- Apr. 28: The End of The Season

- Jun. 12: The 65th Annual Tony Awards - Beacon Theatre

- June 14: Spider-Man, Turn Off The Dark - Foxwoods Theater

- June 21: Master Class - Samuel J. Friedman