[Broadway Ad Network]

[Broadway Ad Network]

TICKET / INFO

- StudentRush

- New York Show Tickets

- Givenik.com

- Telecharge.com

- Ticketmaster.com

- Group Sales Box Office

- Frugal TheaterGoer

- Broadway for Broke People

- Playbill's Rush/Lottery/SR

- Seating Charts

COMMUNITY

NEWS

- Back Stage

- Bloomberg

- Broadway.com

- BroadwayWorld

- Entertainment Weekly

- NYTheatre.com

- New York Magazine

- The New York Daily News

- The New York Post

- The New York Times

- The New Yorker

- Newsday

- NiteLife Exchange

- Playbill

- Show Business Weekly

- The Star-Ledger

- Talkin'Broadway

- TheaterMania.com

- Time Out New York

- American Theatre Magazine

- Theatre Development Fund (TDF)

- Best of Off-Broadway

- The Village Voice

- Variety

- The Wall Street Journal

- Journal News

REVIEWS

- The New York Times

- Variety

- New York Post

- NY1

- Aisle Say

- CurtainUp

- DC Theatre Scene

- Show Showdown

- Stage and Cinema

- StageGrade

- Talk Entertainment

- TotalTheater.com

- Off-Off Broadway Review

- TheaterOnline.com

- TheaterScene.net

- TheaterNewsOnline.com

WEST END

- The Stage

- 1st 4 London Theatre Tickets

- Book Your Theatre Tickets

- Compare Theatre Tickets.co.uk

- Theatre.com

- Whatsonstage.com [UK]

- ATW - London

- Musical Stages [UK]

- Albemarle of London

- Londontheatre.co.uk

- Google News

- Show Pairs

- ILoveTheatre.com

- The Official London Theatre Guide

- UK Tickets

BOSTON

CHICAGO

LA/SF

COLUMNS

- Peter Bart

- Andrew Cohen

- Ken Davenport

- Tim Dunleavy

- Peter Filichia

- Andrew Gans

- Ernio Hernandez

- Harry Haun

- Chad Jones

- Chris Jones

- James Marino

- Joel Markowitz

- Matthew Murray

- Michael Musto

- Ellis Nassour

- Tom Nondorf

- Richard Ouzounian

- Michael Portantiere

- Rex Reed

- Michael Riedel

- Frank Rizzo

- Richard Seff

- Frank Scheck

- Mark Shenton

- John Simon

- Robert Simonson

- Steve on Broadway (SOB)

- Steven Suskin

- Terry Teachout

- Theater Corps

- Elisabeth Vincentelli

- Hedy Weiss

- Matt Windman

- Linda Winer

- Matt Wolf

PODCAST

RADIO

TV

- Theater Talk

- BlueGobo.com

- Classic Arts Showcase

- American Theatre Wing Seminars

- Women in Theatre

- NY1

- WCBS [2]

- WNBC [4]

- FOX [5]

- WABC [7]

- WWOR [9]

- WPIX [11]

- Channel 13

- Hulu

- YouTube

AWARDS

- Tony Central

- Oscar Central

- Tony Awards

- Drama Desk Awards

- The Drama League Awards

- Lortel Awards

- Academy Awards

- Emmy Awards

- Grammy Awards

- GoldDerby

DATABASE

- Internet Broadway Database

- Internet Off-Broadway Database

- Internet Movie Database

- Internet Theatre Database

- Musical Cast Album Database

- [CastAlbums.org]

- Show Music on Record Database (LOC)

- CurtainUp Master Index of Reviews

- Musical Heaven

- StageSpecs.org

ROAD HOUSES

- Gammage [AZ]

- Golden Gate [CA]

- Curran [CA]

- Orpheum [CA]

- Community Center [CA]

- Civic [CA]

- Ahmanson [CA]

- Pantages [CA]

- Temple Hoyne Buell [CO]

- Palace [CT]

- Rich Forum [CT]

- Shubert [CT]

- Bushnell [CT]

- Chevrolet [CT]

- Broward Center [FL]

- Jackie Gleason [FL]

- Fox [GA]

- Civic Center [IA]

- Cadillac Palace [IL]

- Ford Center/Oriental [IL]

- The Bank of America Theatre [IL]

- Auditorium Theatre of Roosevelt University [IL]

- Kentucky Center [KY]

- France-Merrick [MD]

- Colonial [MA]

- Wilbur [MA]

- Charles [MA]

- Wang [MA]

- Wharton Center [MI]

- Whiting [MI]

- Fisher [MI]

- Masonic Temple [MI]

- Orpheum, State, and Pantages [MN]

- Fabulous Fox [MO]

- New Jersey PAC [NJ]

- Auditorium Center [NY]

- Proctors [NY]

- Shea's PAC [NY]

- BTI Center [NC]

- Blumenthal PAC [NC]

- Schuster PAC [OH]

- Playhouse Square [OH]

- Aronoff Center [OH]

- Ohio [OH]

- Victoria Theatre [OH]

- Birmingham Jefferson [OH]

- Merriam Theater [PA]

- Academy of Music [PA]

- Benedum Center [PA]

- Providence PAC [RI]

- Orpheum [TN]

- Hobby Center [TX]

- Music Hall [TX]

- Bass Hall [TX]

- Paramount [WA]

- Fox Cities PAC [WI]

- Marcus Center [WI]

- Weidner Center [WI]

FESTIVALS

- The New York International Fringe Festival

- The American Living Room Festival

- Summer Play Festival

- The New York Musical Theatre Festival

- Adirondack Theatre Festival

- NAMT: Festival of New Musicals

SPECIAL

- BC/EFA: Broadway Cares / Equity Fights AIDS

- The Actors' Fund

- Stage Directors and Choreographers Foundation

EDUCATION

- Google Shakespeare

- Actor Tips

- AACT

- ArtSearch

- Broadway Classroom

- Broadway Educational Alliance

- Camp Broadway

- Great Groups - New York Actors

- Theatre Communications Group (TCG)

- Theatre Development Fund (TDF)

- Off-Broadway Theater Information Center

UNIONS/TRADE

- AEA

- SAG

- AFTRA

- AGMA

- The League

- APAP

- Local 1

- ATPAM

- IATSE

- AFM

- AFM - Local 802

- Treasurers & Ticket Sellers Union

- DGA

- Dramatists Guild

- USA 829

- WGA, East

- WGA, West

- SSD&C

- AFL-CIO

- League of Professional Theatre Women

NYC NON-PROFITS

- Cherry Lane Theatre

- City Center

- Drama Dept.

- Ensemble Studio Theater

- Jean Cocteau Rep.

- Lark

- Lincoln Center Theater

- Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts

- Lucille Lortel Foundation

- Manhattan Theatre Club

- MCC

- Mint

- Pearl Theatre Company

- Public Theater

- Roundabout

- Second Stage

- Signature

- The Vineyard Theatre

- The York Theatre Company

REGIONAL

- Actors Theatre

- Alabama Shakespeare Festival

- Alley Theatre

- ACT

- American Musical Theatre in San Jose

- American Repertory

- Arena Stage

- Barrington Stage Company

- Bay Street Theatre

- Berkeley Rep

- Casa Manana

- Chicago Shakespeare Theater

- Cincinnati Playhouse

- CTC

- Dallas Summer Musicals

- Dallas Theater Center

- Denver Center

- George Street

- Goodman

- Guthrie

- Goodspeed

- Hartford Stage

- Hudson Stage Company

- Theatre de la Jeune Lune

- Kennedy Center

- La Jolla

- Long Wharf

- Lyric Stage

- Mark Taper Forum

- McCarter

- New Jersey Rep

- North Shore

- Old Globe

- Ordway

- Oregon Shakespeare

- Paper Mill

- Prince Music Theater

- The Rep (St. Louis)

- Sacramento Music Circus

- San Francisco Mime Troupe

- Seattle Rep

- Shakespeare Theatre Co. (DC)

- The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey

- South Coast Rep

- Steppenwolf

- Theater of the Stars (GA)

- Theater J (DC)

- Theater Under the Stars (TX)

- Trinity Rep

- Two River Theater Company

- Utah

- Victory Gardens

- Westport

- Williamstown

- Yale Rep

KEWL

JOHN CULLUM: VETERAN STAR OF BROADWAY MUSICALS AND TV TACKLES A DECIDELY DIFFERENT ROLE IN SIN (A CARDINAL DEPOSED)

by Ellis Nassour

-

He also speaks on working with Barbara Harris and Madeline Kahn

As strong an actor in Broadway musicals, comedy and classics and acting and directing on the big and small screen, John Cullum has had a varied career and the unique ability to move smoothly from one medium to the other. At a time when actors his age might be resting on their laurels - and Tony Award nominations and wins, he's Off Broadway portraying a controversial prince of the Roman Catholic Church, Bernard Cardinal Law, in Michael Murphy's Sin (A Cardinal Deposed).Law rose quickly from a parish priest in Mississippi to Bishop, Archbishop, Cardinal and intimate friend of Pope John Paul II. As one of the most trusted and powerful prelates - one who adhered to the pope's conservative agenda, he was often mentioned as a possibility of becoming the first American pope. As head of the archdiocese of Boston, he went from friend of presidents and the powerful and beloved shepherd of his flock to an outcast as he was held accountable in the cover-up scandal involving pedophile priests.

This is a departure role for Cullum. His manager Jeff Berger, who strongly recommended he do Urinetown, was high on the script and having his client work with the Obie-winning and now Tony-winning producer The New Group, founded by Scott Elliott, and most famous for producing Avenue Q.

"What interested me in doing a small play Off Broadway was the quality of Michael's script. It's the type of play that should first be developed, not on Broadway, but a bit off the beaten track. Michael's point was that the material was good. It premiered in Chicago [March 2004, the Bailiwick Repertory Company] and played briefly in the Cardinal's ëhometown,' but because there's a lot of interest in the subject, I felt that it would garner a lot of attention here. It's one of those plays that's really torn from the headlines."

"However," continues Cullum, [since Murphy adapted Sin from several depositions Law was forced by the courts to make], "I thought it might play as documentary theater. I was concerned whether or not it was a drama and if it would work on the stage. If you don't bring something interesting to this type of thing, it can get static. As it is, after I enter and sit, I never get up out of the chair until my exit."

He credits director Carl Forsman for taking the play to another level. "Carl's one of these young, firebrand directors - full of energy and enthusiasm. He talks too fast for me, so I had to make an effort to keep up with him. Whenever there was anything I really wanted to know, I'd just say, ëHey, say that again!' He did interesting things, such as taking some of the other actors out of earshot and giving them directions I wasn't aware of to get spontaneous reactions out of me."

Forsman is also artistic director of Keen Company, where he directed, among other works, The Journals of Mihail Sebastian and The Voice of the Turtle [Drama Desk nomination]. He recently directed the premiere of Tina Howe's new translations of Ionesco's The Bald Soprano and The Lesson at the Atlantic Theater Company.

Murphy had a vast amount of material from which to choose and composited several days of depositions into one highly-charged 90 minutes with what he felt were some searing moments. "The choice of material changed from the start rehearsals until previews," says Cullum. "It's been an evolving piece and an exhausting process."

"I'm amazed at how many people stay to meet me afterward and what they have to say," he reports. "For a few days, I avoided going out the front door." Cullum received letters from longtime fans, congratulating him for taking on such a role, then came the other letters -- from those who said they were victims and who wanted to Cullum.

One letter, from William J. Curtis Jr. of New Jersey, read in part [quoted with permission]:

"I am a survivor of clergy abuseÖI am a firm believer in the power of theatre to inform minds and transform heartsÖperforming Sin in New York will spark further discussion of both the clergy abuse scandal and the unfortunate response of much of the Catholic hierarchyÖ[Because of the abuse inflicted] I struggled with trust issues and relationship problems. I had problems with alcoholÖand entertained suicideÖI also lost faith in the Church that I was raised and thrived inÖI reported my abuse to the Church in 1993 (eleven years after the fact) and was glad-handed but ultimately ignoredÖI went to themÖthinking that they would do the right thing. I was haunted by guilt knowing that my abuser was still in service with access to other kids and I had not tried to stop him. The archdiocese chose to believe my abuser's story of denial rather than my truthÖ"Curtis is but one of thousands of cases across the country. "It was letters like his," explains Cullum, "that made me realize that in some way I could be a conduit for their concerns and frustrations. Some treat me as if I am a real Cardinal and, strangely, show me a weird, loving respect. It's a bit spooky."

Cullum, born in Knoxville and raised Baptist, says he wasn't interested in being in a play that bashed the Catholic Church. I have many Catholic friends and never put much credence in what we were taught - that Catholics would go to hell. [Ironically, Catholics, in the days before Pope John XXIII and the Second Vatican Council, were taught that to get to Heaven you had to belong to "the one true church."] I was interested because of the drama of how greed and power can lead to terrible circumstances -- how a man of such superb intelligence could be blindsided by events. Abuse of children in a religious institution can be covered up just like a lot of other things. I was relieved when Catholic friends saw the play and didn't express negative feelings toward me or Michael."

Murphy's play exposes the Church's disregard, over too many years, for the victims of pedophile priests. He's been developing Sin over two years. "When I'm asked why I chose this topic to write," he explains, "I say I had to find out for myself how this scandal was allowed to happen. If we think about Law as that young, talented, hard-working, charismatic priest in Mississippi, it seems impossible that what transpired could happen on his watch. What a tragedy. Law was also ambitious, and this seemed to create a discernable arc in his career. In Missouri, as a bishop, he became more respected than liked. In Boston, he became imperious and distant."

Cullum has one of his most powerful moments at the play's finale when Thompson asks a pointed question. "Law has no answer," says Cullum. "Maybe there is no answer. The crux of the entire play is embraced in that moment and the Cardinal's lack of response. Everyone knows the answer, but he cannot make himself give it."

The star says he's excited to be working with such a talented ensemble -- one which has three standout actors: Pablo T. Schreiber [HBO's The Wire, NYSF, Off Broadway's Blood Orange -- who's the very tall brother of Liev Schreiber], playing victim Patrick McSorley, looms over the proceedings in silence but provides a scorching denouncement as a tag line to the play; Cynthia Darlow [Broadway, Present Laughter, Prelude to a Kiss; Off Broadway, The Cider House Rules], portraying several characters ranging from a victim's mother to a nun; and Thomas Jay Ryan [Rounabout's Juno and the Paycock], who's unrelenting as the attorney representing the victims.

Since Cullum has been on both sides of the footlights, it's natural to ask if it's difficult to be directed when you've directed? "Not at all," he states. "In fact, it makes me more empathic with them. I have more sympathy because I understand what they're going through. I don't think of myself as a good director because I want actors to be exactly what I want them to be.

"When I watch Carl," he continues, "I see he knows what he wants but he wants to find out what you can bring to it. He's always probing and searching and discussing it with us. He's not interested in me doing what he wants to do, but in my getting across the ideas we agree on and finding ways to make it personal and believable. It's a method that's not totally foreign to me. However, I still find it refreshing because I haven't worked that way much."

John Cullum, after graduation from the University of Tennessee, became a standout tennis player, winning the 1951 Southeastern Conference doubles championship with Bill Davis. As a young actor, performing in his home town, he met dancer/choreographer, now writer, Emily Frankel "and that was the end of that or, rather, the beginning." They married and have a son, actor JD Cullum. Recently, father and son performed in The Dresser at Knoxville's Clarence Brown Theatre.

After getting started in New York with the Shakespearwrights, a classics group that predated Joe Papp and the Public Theatre, Cullum made his Broadway debut was in 1960 as Sir Dinadan [and understudy to Arthur and Mordred] in Camelot, starring Richard Burton and Julie Andrews. Other highlights: the 1964 Burton Hamlet, playing Laertes, directed by John Gielgud; his Tony nomination for his portrayal of psychiatrist Mark Bruckner in Lerner and Lane's On A Clear Day You Can See Forever [1965] opposite Barbara Harris; replacing Richard Kiley [1967, for over a year] in Man of La Mancha; as a replacement in the Edward Rutledge role in 1969's Tony-winning 1776, a part he recreated onscreen; his Best Actor/Musical Tony and Drama Desk Award as Civil War farmer Charlie Anderson in Shenandoah [1975]; and his Best Actor/Musical Tony for Coleman/Green and Comden's On the Twentieth Century [1978], in which he played egomaniacal Broadway impresario Oscar Jaffee opposite Madeline Kahn and Imogene Coca, featuring Kevin Kline and directed by Hal Prince.

Cullum starred opposite Taylor and Burton in 1983's Private Lives revival. His expertise at tennis came in handy for the eight-month run of the 1985 comedy, Doubles. In 1986, he starred with the formidable George C. Scott in the two-hander The Boys In Autumn. Later, he appeared as Captain Andy in Prince's Show Boat revival; and received a 2002 Tony-nomination for his portrayal of Urinetown's mayor.

He's had his share of talented, famous and temperamental co-stars - female and male. But Cullum, known as an all-around good-guy, is, as one colleague described him, "the calm in rough seas." There have been trying times, and he doesn't mind talking about them - especially when a show's team tried to pit him against one of his co-stars.

"Barbara Harris and Madeline Kahn were very unusual, but very multi-talented ladies," he relates. "I loved them both." That's not to say that they weren't difficult? "Sometimes," says Cullum softly. "Barbara [in Clear Day]," , was difficult in the sense that she was moody. I don't know if that was based on arrogance or lack of confidence. She had a background totally different than most Broadway people, so that stage discipline was missing. She was very improvisational. I never knew what she was going to do from performance to performance. That said, if you walked on a stage with Barbara Harris, you were lucky if anyone even noticed you were there. She had this incredible radiance and was magic onstage.

"Early on, I don't think Barbara was that fond of me," he continues. "At least, she was very cool to me. Most of the time, she was very reserved and nervous. That is not to say she could be as charming as possible. She could be. But, eventually, we all got along. [Director] Robert Lewis and Alan [Jay Lerner} squashed into a role that I really didn't get to contribute very much to. They had me speak in a Viennese accent, bouffed up my hair and put me into these really chic outfits to make me look like a six-foot Alan Jay Lerner. So I was uncomfortable in that role for a long time. If they'd turned me loose a little, I could have done a lot better."

Kahn, explains Cullum, was eccentric. "She was tiny in stature but had the sort of presence that could take over a stage"" On why she left Twentieth Century almost as soon as it opened: "That could have been avoided. The show didn't work out of town and there were a bunch of nervous people. Things didn't started to gel until four days before we opened."

One of the problems, he says, was that the "star" of the show was the set and the set didn't work. On top of that, there'd been massive cuts and rewriting, so much so that it created tension between Kahn and composer Coleman. "Cy had her going on and singing material cold," Cullum recalls. "Madeline also felt, he'd written things difficult for her to sing. She kept asking him to take things [keys] down a bit. When he didn't, she did. Cy got upset with Hal and Hal got upset with Madeline, who was already upset with Cy."

Cullum says that Prince and Coleman came to the conclusion that Kahn "was going to leave" much too quickly "because she was wonderful. They tried to get me to turn against her. I told them, ëForget it. I'm not getting in the middle. She's my star.' I resented the fact that they wanted me to run her down."

After two weeks of previews and a week after the opening, Judy Kaye stepped in to play Carlotta. "Judy was a joy to work with," says Cullum. "Of course, she was totally different. Whereas Madeline was the model of that caricature of the high-strung, volatile Hollywood star, Judy's was a robust, straight-forward, kind of knock ëem dead sort of thing."

But, he explains, these type goings on never end. He points to the crisis last year at Manhattan Theatre Club when playwright Neil Simon personally and publicly came down on Mary Tyler Moore, with whom Cullum was starring in Rose's Dilemma. "Everything was all confused and terrible, and they tried to turn me against Mary. What happened was unfortunate and never should have occurred. When this happens, I get upset with producers, directors and playwrights."

He recounts a situation in 1977, in Washington, when he was starring with Bibi Andersson, the Swedish film star famous for her work with Bergman, in Arthur Miller's The Archbishop's Ceiling. "Arthur and our producer Robert Whitehead turned on Bibi. Robert was considered the most sophisticated producer and Miller, one of our greatest playwrights, but they blamed her for the first act not working. She was quite good. They thought so, too, because they cast her; but when you get into a situation where things aren't going well, the creative team will turn on everybody but the ones to blame. You could blame the director and the playwright, but usually it's the actor who gets the shaft."

Cullum has also worked with his share of scene-stealers, but none better than Imogene Coca in Twentieth Century. "She had the most incredible comic instincts," he says, "and energy to burn. You just didn't get in her way!" He explains that Tammy Grimes was, too, but in a different way. "She was difficult and headstrong. When we did Clear Day in California, she was looking for every way she could do it differently than Barbara. Unfortunately, she took her frustrations out on me a lot of times. But we got that straightened out! I tend to do that. I'm not a ëprima donna.' I think I'm pretty reasonable in the professionalism I expect from others."

Offstage, Cullum made his film debut in 1963's All the Way Home, based on Tad Mosel's play. There were numerous TV and theatrical films, two daytime soaps and three TV series. But the small screen standout is Cullum's household name/star making five-year stint in CBS' Northern Exposure as barkeep Holling [1993 Emmy Nomination - Best Supporting Actor in a Drama]. He later appeared for a season on NBC's E.R.

The step from Broadway to TV stardom was something that happened so casually, it took Cullum unawares. "For some reason," he recalls, "I got called in to do a tape audition - maybe it was because of Shenandoah. Then, out in L.A., I was brought in to audition with some big guns, one of whom was a western star. Another was an actor who played my brother on Broadway in 1977's The Trip Back Down. They seemed to be looking for a burly, athletic guy. I did my thing, going for the wry humor in the script, and didn't think much about it."

A couple of days later, the phone rang and my agent said they wanted him to do it. "And," laughs Cullum, "they had no idea who I was. They never knew I'd done anything on Broadway. Around the third episode, there was an occasion for the radio station to play songs from Broadway shows. One album they selected was On A Clear DayÖ I realized that if they played the title song, they'd be hearing me. Who I was came as quite a revelation.

"We were a bunch of eclectic guys," he continues. "I knew some of them, like Barry Corbin and, from his acting company here, Rob Morrow. Then there was sweet Cynthia Geary [who's a native of Jackson, MS] as Shelly Marie. I also had met Jeanine Turner, because I tried to get her cast in a film I'd done. My film and TV experience was limited, so I just was my natural self. We did five episodes over the summer and then CBS picked us up for a full season. I wasn't stunned we became a hit, because the characters were fun and the show had a very fresh approach. It was not easy going. We worked long hours, six days a week, which was rough in itself since we weren't on studio soundstages but shooting in a former warehouse in Bellevue, Washington. It developed in an interesting way, because before you knew it, the writers were writing directly off those of us playing the roles."

To TV audiences, Cullum was an unknown. Audiences might have known who he was if he had chosen to tour with his hit musicals, but he didn't. "I wasn't interested in traveling and, frankly, they weren't interested in having me. They wanted movie stars."

Sin (A Cardinal Deposed), presented by The New Group, at the Clurman on Theatre Row, 410 West 42nd Street, is set to run into early December. After that, and a little relaxing, Cullum is considering TV projects and a possible reading for a major non-profit.

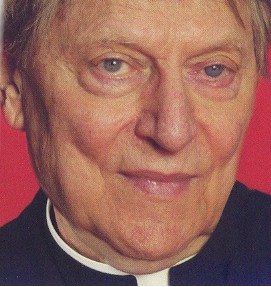

John Cullum as controversial Bernard Law in Sin (A Cardinal Deposed)~John Cullum in 1964's Burton Hamlet with Hume Cronyn; On A Clear Day You Can See Forever (1966); with Clear Day co-star Barbara Harris; and after joining 1776 (1969), to play Edward Rutledge, opposite Howard DeSilva as Benjamin Franklin

John Cullum as controversial Bernard Law in Sin (A Cardinal Deposed)~John Cullum in 1964's Burton Hamlet with Hume Cronyn; On A Clear Day You Can See Forever (1966); with Clear Day co-star Barbara Harris; and after joining 1776 (1969), to play Edward Rutledge, opposite Howard DeSilva as Benjamin Franklin

Bernard Cardinal Law in good and bad times:

[Author's note: Bernard Cardinal Law's first assignment after seminary in Louisiana was my parish in Vicksburg, MS. He was young and had a different mindset than the priests we were accustomed to. Because of the lack of MS vocations, most of our priests were imported from Ireland. Father Law was one of us. He had personality plus and, for having attended Harvard, was immensely intelligent. Our mothers were the best of friends. During his time in MS, he was progressive and ecumenical in opening doors to other faiths; and he openly preached against segregation. As he rose through Church ranks, as editor of our Catholic newspaper, becoming a Bishop, Cardinal and intimate friend of the Pope, we were immensely proud of our "Father" Law. In Boston, on several occasions, I saw how loved he was. Since he was a people person, he'd greet everyone after services. As the scandal broke, the immense cathedral was all but empty with hundreds of protesters and media reporters outside. Instead, of Cardinal Law's usual meet and greet, he would exit the altar and zip off in his chauffeured sedan. None who knew and admired the Cardinal would have expected him to handle the priest pedophile scandal as he did. ]

--------Ellis Nassour is an international media journalist, and author of Honky Tonk Angel: The Intimate Story of Patsy Cline, which he has adapted into a musical for the stage. Visit www.patsyclinehta.com.

He can be reached at [email protected]

Why are you looking all the way down here?

For more articles by Ellis Nassour, click the links below!

Previous: MOVIN' OUT ENTERS THIRD YEAR AND TONY NOMINEE JOHN SEYLA IS STILL SOARING THROUGH THE AIR AT LIGHTNING SPEEDS

Next: Showstopping Holiday Gift Suggestions: Part 1

Or go to the Archives

[Broadway Ad Network]

[Broadway Ad Network]

If you would like to contact us, you can email us at feedback@

broadwaystars.com

[Broadway Ad Network]

[Broadway Ad Network]

- July 15: Harry Connick, Jr. in Concert on Broadway - Neil Simon

- Sept. 28: Brief Encounter - Studio 54

- Sept. 30: The Pitmen Painters - Samuel J. Friedman Theatre

- Oct. 3: Mrs. Warren's Profession - American Airlines Theatre

- Oct. 7: Time Stands Still - Cort Theatre

- Oct. 12: A Life In The Theatre - Schoenfeld Theatre

- Oct. 13: Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson - Bernard Jacobs Theatre

- Oct. 14: La Bete - The Music Box Theatre

- Oct. 21: Lombardi - Circle In The Square

- Oct. 25: Driving Miss Daisy - John Golden Theatre

- Oct. 26: Rain - A Tribute To The Beatles On Broadway - Neil Simon Theatre

- Oct. 31: The Scottsboro Boys - Lyceum Theatre

- Nov. 4: Women On The Verge Of A Nervous Breakdown - Belasco Theatre

- Nov. 9: Colin Quinn Long Story Short - Helen Hayes Theatre

- Nov. 11: The Pee-Wee Herman Show - Stephen Sondheim Theatre

- Nov. 13: The Merchant of Venice - The Broadhurst Theatre

- Nov. 14: Elf - Al Hirschfeld Theatre

- Nov. 18: A Free Man Of Color - Vivian Beaumont Theater

- Nov. 21: Elling - Ethel Barrymore Theatre

- Dec. 9: Donny & Marie: A Broadway Christmas - Marquis Theater

- Jan. 13: The Importance of Being Earnest - American Airlines Theatre

- Mar. 3: Good People - Samuel J. Friedman Theatre

- Mar. 6: That Championship Season - Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre

- Mar. 11: Kathy Griffin Wants a Tony - Belasco

- Mar. 17: Arcadia - Barrymore Theatre

- Mar. 20: Priscilla Queen Of The Desert The Musical - The Palace Theatre

- Mar. 22: Ghetto Klown - Lyceum Theatre

- Mar. 24: The Book Of Mormon - Eugene O'Neill Theatre

- Mar. 27: How To Succeed In Business Without Really Trying - Al Hirschfeld Theatre

- Mar. 31: Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo - Richard Rodgers Theatre

- Apr. 7: Anything Goes - Stephen Sondheim Theatre

- Apr. 10: Catch Me If You Can - The Neil Simon Theatre

- Apr. 11: The Motherf**ker with the Hat - Gerald Schoenfeld Theatre

- Apr. 14: War Horse - Vivian Beaumont Theater

- Apr. 17: Wonderland: A New Alice. A New Musical Adventure. - Marquis Theatre

- Apr. 19: High - Booth Theatre

- Apr. 20: Sister Act - The Broadway Theatre

- Apr. 21: Jerusalem - Music Box

- Apr. 24: Born Yesterday - Cort Theatre

- Apr. 25: The House of Blue Leaves - Walter Kerr Theatre

- Apr. 26: Fat Pig - Belasco Theatre

- Apr. 27: Baby It's You! - Broadhurst Theatre

- Apr. 27: The Normal Heart - Golden Theater

- Apr. 28: The People in the Picture - Studio 54

- Apr. 28: The End of The Season

- Jun. 12: The 65th Annual Tony Awards - Beacon Theatre

- June 14: Spider-Man, Turn Off The Dark - Foxwoods Theater

- June 21: Master Class - Samuel J. Friedman